-

National Foundation Day — A Day to Reflect on Japan’s Beginnings

建国記念の日――日本の「はじまり」を考える日- Hiragana Times

- Jan 28, 2026

[Japan savvy – February 2026 Issue]

National Foundation Day — A Day to Reflect on Japan’s Beginnings

建国記念の日――日本の「はじまり」を考える日

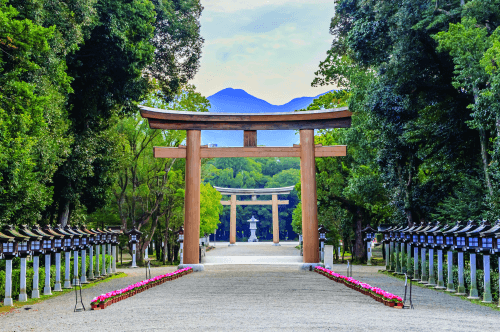

February 11th, which is ‘National Foundation Day’, is the day when it is said that the first Emperor, Emperor Jimmu, ascended the throne.

「建国記念の日」である2月11日は、初代天皇・神武天皇が即位したと伝えられる日です。

That year is considered to be 660 BC, and His Majesty the current Emperor corresponds to the 126th generation counting from there.

その年は紀元前660年とされ、現在の天皇陛下は、そこから数えて126代目にあたります。

It was in the Meiji era, when relationships with Western powers began to deepen, that this day was first established.

この日が最初に定められたのは、「西洋列強」との関係が深まりはじめた明治時代でした。

Japan named this day ‘Kigensetsu’ in order to show its own origin to the international community.

日本は国際社会に向けて、自らの起源を示すため、この日を「紀元節」と名づけました。

After World War II, Kigensetsu was abolished once under the occupation policy, but after that, receiving the voices of the people, it revived changing its name to ‘National Foundation day.

第二次世界大戦後、占領政策のもとで紀元節はいったん廃止されますが、その後、国民の声を受けて「建国記念の日」と名を変えて復活します。

In Japanese mythology, there is a story called ‘Kuniyuzuri’ (Transfer of the Land), which is said to have ceded the country to the lineage of Emperor Jimmu.

日本の神話には、神武天皇の系譜に国を譲ったとされる「国譲り」という物語があります。

In it, it is told that a ‘country’ existed in this Japan even before ‘Kigensetsu’.

そこには、「紀元節」以前にも、この日本に「国」が存在していたことが語られています。

National Foundation Day is a day to turn one’s thoughts to Japan’s endlessly long history.

建国記念の日は、日本の果てしなく長い歴史に想いを馳せる日です。

Become a Kenkoku Savvy 建国通になる

WARM UP | Kenkoku JapaNEEDS

Useful Words 役立つ言葉

- 建国記念の日(けんこくきねんのひ) – National Foundation Day

- 即位(そくい) – enthronement; accession to the throne

- 神武天皇(じんむてんのう) – Emperor Jimmu

- 紀元前(きげんぜん) – BCE (Before the Common Era)

- 紀元節(きげんせつ) – National Foundation Day

- 起源(きげん) – origin

- 国際社会(こくさいしゃかい) – international community

- 神話(しんわ) – mythology

- 国譲り(くにゆずり) – transfer of the land (myth)

- 系譜(けいふ) – lineage

- 歴史(れきし) – history

- 想いを馳せる(おもいをはせる) – to reflect on; to think back

Ice Breaker Questions 会話のきっかけ

1.Does your country have a day that commemorates its founding?

あなたの国には、「建国」を記念する日がありますか?

2.What kind of event is that day based on?

その日は、どんな出来事をもとに定められていますか?

3.Do you think a nation’s beginning can be clearly defined?

「国のはじまり」は、はっきり決められるものだと思いますか?

4.Do you see mythology as history, or as a story?

神話は、歴史だと思いますか?それとも物語だと思いますか?

5.What kind of day makes you feel a sense of “beginning”?

あなたにとって、「はじまり」を感じる日はどんな日ですか?

WORK UP | Kenkoku Discussion

DISCUSSION ディスカッション

Michael: America’s Independence Day is July 4th, marking 1776, when the Declaration of Independence was issued.

マイケル:アメリカの建国記念日は、1776年に独立宣言が出された7月4日です。

Mayumi: That was the day George Washington and others declared independence from Britain, right?

まゆみ:ジョージ・ワシントンたちがイギリスからの独立を宣言した日ですね。

Emily: The UK doesn’t actually have a “National Foundation Day.”

That’s because our monarchy and political system evolved gradually over time.エミリー:イギリスには、実は「建国記念日」はありません。王朝や国の形が、少しずつ変わってきたからです。

Ming:In China, we celebrate National Day on October 1st, marking 1949, when Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

ミン:中国では、1949年10月1日に毛沢東が中華人民共和国の成立を宣言した日を、「国慶節」として祝います。

Pierre: In France, we celebrate July 14th to commemorate the French Revolution of 1789. Our nation begins not with a dynasty, but with the revolution itself.

ピエール:フランスでは、1789年のフランス革命を記念する7月14日を祝います。王朝のはじまりではなく、「革命」そのものが国の出発点なんです。

Mayumi: Looking at it this way, many countries define their beginnings through clear historical events. In Japan, however, the founding of the nation is told alongside mythology.

まゆみ:こうして見ると、多くの国は、はっきりした「歴史的な出来事」を建国の始まりにしているんですね。日本の場合、建国は神話と重ねて語られます。

Emily: That’s the story in which the land of Izumo was said to have been handed over to the lineage of Emperor Jimmu, a descendant of the sun deity, right?

エミリー:出雲の国が、太陽の神の子孫である神武天皇の系譜に、国を譲ったという物語ですね。

Ming: The birth of the nation itself sounds almost like a Studio Ghibli film.

ミン:国の誕生そのものが、まるでジブリアニメみたいですね。

Pierre: Anime, or should I say, animism. That’s what you’d expect from a country rooted in nature worship.

ピエール:アニメならぬ、アニミズム。自然崇拝の国ならではですね。

WORK UP | Osechi Discussion

DISCUSSION ディスカッション

In Japan, people are given a posthumous name (okurina) based on how they lived and what they achieved after their death.

日本では、死後その人の生き方や功績などをもとに、諡(おくりな)が与えられます。

The name Emperor Jimmu is also a posthumous title; his name during his lifetime was Iwarebiko (Kamuyamato Iwarebiko).

神武天皇という名も諡であり、生前の名はイワレビコ(神日本磐余彦〈かむやまと・いわれびこ〉)でした。

It is said that before the establishment marked by Kigensetsu, there existed what is often referred to as the Izumo dynasty.

紀元節以前には、「出雲王朝」が存在したと伝えられています。

The Japanese archipelago is crossed by mountain ranges that run like a backbone through the land; the Sea of Japan side is called San’in, while the Pacific side is known as San’yō.

日本列島には山脈が背骨のように連なり、日本海側は山陰、太平洋側は山陽と呼ばれています。

In Japan, Hyuga City in Kyushu is written as “where the sun turns,” Hitachi City in eastern Japan as “where the sun stands,” and Izumo City in the San’in region as “where clouds appear.”

日本には、日が向かうと書く「日向市」が九州に、日が立つと書く「日立市」が東日本に、そして雲が出る「出雲市」が山陰にあります。

“Izumo,” now located in Shimane Prefecture, is thought in ancient times to have extended its influence from the Sea of Japan coast, across the mountains, and into the Nara Basin, a key geographical crossroads.

現在、島根県に位置する「出雲」は、古代においては、日本海側から山々を越えた、地形の切れ目である奈良盆地にまで、その影響を及ぼしていたと考えられています。

Iwarebiko (Emperor Jimmu) is said to have been born in the area around Hyuga in Kyushu.

イワレビコ(神武天皇)は、九州の日向のあたりで生まれたと伝えられています。

In the story of his eastern expedition toward Nara, there appears a figure named Nigihayahi, who is described as having ruled the Kinai region before Jimmu.

イワレビコが奈良へと向かう東征の物語には、ニギハヤヒ(饒速日)と呼ばれる、神武天皇以前に畿内を統治していたとされる存在が語られています。

Some scholars view Nigihayahi as a ruler who preceded Emperor Jimmu—sometimes described as a kind of “zero-generation emperor.”

このニギハヤヒ(饒速日)を、神武天皇以前の支配者、いわば「ゼロ代天皇」のような存在として捉える研究者もいます。

This article is from the February 2026 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2026年2月号より掲載しています。

-

Shogatsu—Osechi Cuisine Celebrating the “Fushi” (Nodes) of the Sun and Moon

正月――太陽と月の節(ふし)を祝うお節料理- Hiragana Times

- Jan 03, 2026

[Japan Savvy – January 2026 Issue]

Shogatsu—Osechi Cuisine Celebrating the “Fushi” (Nodes) of the Sun and Moon

正月――太陽と月の節(ふし)を祝うお節料理‘Osechi ryori’ is indispensable for the Japanese New Year.

日本のお正月に欠かせない「おせち料理」。

It is a special cuisine that celebrates the new year, with various dishes beautifully packed in ‘jubako’ (tiered boxes).

いろいろな料理を重箱に美しく詰めた、新しい年を祝う特別な料理です。

In kanji, it is written as “御節料理” (Osechi Ryori).

漢字では「御節料理」と書きます。

This ‘sechi’ (node/season) is read as ‘fushi’ in Yamato Kotoba (native Japanese words).

この「節(せち)」は、大和言葉では「ふし」と読みます。

‘Fushi’ is a switching point of things, and it means a regeneration point where new life is born again.

ふしとは、ものごとの切り替わりであり、新たな生命が生まれ直す再生点を意味します。

The sun weakens the most in the year, and the turning point where it begins to regain its power again from there is the ‘Winter Solstice’.

太陽が一年で最も弱まり、そこから再び力を取り戻し始める転換点──「冬至」。

That is the moment when ‘Yin’ reaches its extreme and ‘Yang’ is born. And, the new moon that comes around before long.

それは、陰が極まり、陽が生まれる瞬間です。そして、やがて巡ってくる新月。

It is the time when the moon returns to darkness once, and begins to harbor light from there.

月がいったん闇に戻り、そこから光を宿し始める時です。

At the Winter Solstice, the sun is born anew, and with the new moon that follows, the moon is born anew as well—

冬至で太陽が生まれ直し、続いて訪れる新月で月が生まれ直す──

Ancient people living under the lunar calendar celebrated this great “Fushi” (node) of the universe—where these two rebirths overlap—as ‘Shogatsu’ and ‘Gantan’.

太陰暦に生きていた古代の人々は、この二つの再生が重なる宇宙の大きな節(ふし)を「正月」「元旦」として寿ぎました(ことほぎました)。

And the cuisine that celebrates that “Fushi” is Osechi Ryori.

そしてその節を祝う料理が、お節料理なのです。

Become a Osechi Savvy おせち通になる

WARM UP | Osechi JapaNEEDS

Useful Words 役立つ言葉

正月(しょうがつ) – New Year御節料理(おせちりょうり) – New Year’s dishes

節(ふし) – joint; node; turning point

再生(さいせい) – renewal; rebirth

冬至(とうじ) – winter solstice

新月(しんげつ) – new moon

太陰暦(たいいんれき) – lunar calendar

重箱(じゅうばこ) – tiered food box

祝う(いわう) – to celebrate

寿ぐ(ことほぐ) – to offer congratulations

意味(いみ) – meaning

願う(ねがう) – to wish; to hope

生命(いのち) – life

Ice Breaker Questions 会話のきっかけ

1. Which osechi dish would you most like to try?

おせち料理の中で、一番食べてみたいものは何ですか?2. What New Year’s traditions or customs do people follow in your country?

あなたの国では、お正月にどんな行事や習慣がありますか?3. Within the year, what day is considered the most important in your country?

一年の中で、あなたの国ではいちばん大切にしている日はいつですか?4. How would you like to spend this New Year’s holiday?

今年のお正月は、どんなふうに過ごしたいですか?5. What is the wish you most hope to come true this year?

今年、あなたが一番かなえたい願いは何ですか?WORK UP | Osechi Discussion

DISCUSSION ディスカッション

Ali: What’s your favorite dish in osechi ryōri?

アリ: おせち料理では、みなさん何が好きですか。

Bob: I like black soybeans!

ボブ: 黒豆が好き!

Mayumi: They represent the wish to “work diligently” and “stay healthy,” because mame also means “hard-working.”

まゆみ: 黒豆には「まめに働く」という願いが込められています。

Vanessa: I love the luxurious sea bream! It literally means “good fortune,” right?

ヴァネッサ: 私は豪華な鯛!これは「めでたい」という意味ですよね?

Bob: Wait—does every osechi dish have some kind of meaning like that?

ボブ: もしかして、おせちって全部そんなふうに意味があるんですか?

Mayumi: Exactly! Each dish has a special wish behind it—not only in the wordplay, but also in the food itself. For example, kazunoko is full of symbolism for future generations. And kurikinton is golden, so it represents wealth and good fortune.

まゆみ: その通りです!おせちはそれぞれ、言葉遊びだけでなく、食材そのものにも意味が込められています。たとえば数の子は子孫繁栄、栗きんとんは黄金色から財運をもたらします。

Ali: I see. Even the shape and color of the ingredients have meanings.

アリ: なるほど。食材の形や色、意味があるんですね。

Mayumi: That’s right. In Japan, people traditionally believed the sound of words, as well as colors, shapes, and numbers, all carry a kind of spiritual power.

まゆみ: そうなんです。日本では、言葉の響きや色、形、数字などにも、それぞれ力が宿ると考えられてきました。

Bob: All right! My New Year’s resolution is to “chew well.” I want to savor the meaning of each dish and live this year mindfully.

ボブ: よし!今年の新年の抱負はよく噛むことにします。一つ一つのおせちの意味を味わいながら、一年を大切に過ごす!WRAP UP | Osechi Knowledge

NEW KNOWLEDGE 新しい知識

Osechi is prepared at the end of the year. This is because using a knife during the New Year period is believed to “cut off” good relationships or good fortune.

おせちは年末に準備します。これは、お正月に包丁を使うと「縁を切る」と考えられてきたためです。It is also said that people should avoid using fire during the first three days of the year, so as not to anger Kōjin, the deity of fire.

また、三が日は火を使わない方が良いとされ、火の神である荒神様を怒らせないためだと伝えられています。For these reasons, many osechi dishes are seasoned strongly so that they will keep for several days.

そのため、おせち料理は日持ちするように、味付けが濃いものが多くなります。The stacked lacquered boxes (jūbako) symbolize the wish for “layers of good fortune.”

重箱には、「福が重なりますように」という願いが込められています。Shrimp represents longevity, with the hope that one will live long enough for one’s back to bend like a shrimp.

えびは、「腰が曲がるまで長生きできますように」という長寿の象徴です。Datemaki resembles a scroll, so it is eaten with wishes for academic success and increased knowledge.

伊達巻は巻物に似ていることから、学問成就や知識向上を願う料理です。Kobumaki (kelp rolls) is associated with the word yorokobu (“to be happy”), and it also symbolizes long life as “yōro-kombu,” meaning longevity kelp.

昆布巻は、「喜ぶ」にかけて縁起を担うほか、「養老昆布」として長寿を願う意味もあります。Kama-boko is considered auspicious because its shape resembles the rising sun on New Year’s Day.

かまぼこは初日の出を思わせる形で、縁起の良い食べ物とされています。

This article is from the January 2026 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2026年1月号より掲載しています。

-

[Japan Savvy – December 2025 Issue]

Year-End Cleaning —Purifying for the New Year

大掃除 ― 清めて迎える新しい年

December is the month that concludes the year.

12月は、1年の締めくくりの月です。

In Japan, it is also a month for expressing gratitude for having passed the year safely, and for making preparations to greet the new year pleasantly.

日本では、1年間を無事に過ごせたことへの感謝と、気持ちよく新しい年を迎えるための準備をする月でもあります。

A representative custom of this is the ‘Ōsōji’ (big cleaning).

その代表的な習慣が「大掃除」です。

Unlike regular cleaning, people polish every nook and cranny of the house until it sparkles.

普段の掃除とは違い、家の隅々までピカピカに磨き上げます。

This custom was already practiced among the common people in the Edo period, but at that time it was called ‘Susu-harai’ (soot sweeping).

この習慣は、江戸時代にはすでに庶民の間で行われていましたが、当時は「煤払い(すすはらい)」と呼ばれていました。

Susu-harai was held on December 13th and was a sacred event for welcoming the ‘Toshigami-sama’ (New Year’s deity).

煤払いは12月13日に行われ、「年神様」を迎えるための神聖な行事でした。

The word ‘harau’ is written both as ‘払う’ (to sweep/pay) and ‘祓う’ (to exorcise/purify).

「はらう」という言葉は、「払う」とも「祓う」とも書きます。

The former expresses the action of sweeping away physical things, while the latter expresses the act of purifying misfortune and defilement.

前者は物を払う動作を、後者は厄や穢れを祓う行為を表します。

In other words, it contains the wish to cleanse not only the dirt of the year but also the misfortune of the heart.

つまり、1年の汚れとともに、心の厄をも清めるという願いが込められているのです。

Cleaning is an act that purifies not only the space but also the heart.

掃除とは、空間だけでなく心をも清める行いなのです。

Perhaps it is a daily ‘sacred ritual’ that is passed down even today.

今も受け継がれる、日々の「神事」なのかもしれません。

”Warm Up ウォームアップ”

”Warm Up ウォームアップ”O-Souji JapaNEEDS

Useful words

- 締めくくり(しめくくり)― conclusion, end

- 無事(ぶじ)― safely, without trouble

- 気持ちいい(きもちいい)― feel good, pleasant

- 準備(じゅんび)― preparation

- 習慣(しゅうかん)― habit, custom

- 大掃除(おおそうじ)― year-end cleaning

- ピカピカ(ぴかぴか)― shiny, sparkling clean

- 煤(すす)― soot

- 神聖(しんせい)― sacred, holy

- 祓う(はらう)― to purify, exorcise

- 清める(きよめる)― to cleanse, purify

- 空間(くうかん)― space

- 心(こころ)― heart, mind

Ice Breaker Questions

Do people in your country do a year-end cleaning?

あなたの国では、大掃除をしますか?How often do you usually clean your home?

ふだん、どのくらいの頻度で掃除をしますか?How do you feel after cleaning?

掃除のあとは、どんな気持ちになりますか?Is there anything you want to do before welcoming the New Year?

新しい年を迎える前に、やっておきたいことはありますか?What do you do when you want to calm or refresh your mind?

気持ちを整えたいとき、どんなことをしますか? ”Work Up ワークアップ”

”Work Up ワークアップ”O-Souji Discussion

Louise: Streets in Japan are so clean! You hardly ever see any trash lying around.

ルイーズ: 日本って、道にゴミがほとんど落ちていませんよね。Jose: Yes, even after the World Cup, Japanese supporters were cleaning up the stands!

ホセ: サッカーのワールドカップのあとも、日本人のサポーターがスタンドを掃除していましたね!Anisa: Do Japanese people actually enjoy cleaning? It looked like a fun event!

アニサ: 日本人は、そうじが楽しいんですか?まるでイベントみたいでしたよ!Yumi: That’s true, but rather than “fun,” it’s more like a habit we learn from childhood.

ゆみ: そうですね。でも“楽しい”というより、子どものころからの習慣なんですよ。Louise: I heard that in Japanese elementary schools, students clean their classrooms every day.

ルイーズ: たとえば、日本の小学校では、みんなで毎日掃除をするんですよね?Bob: Really? In my country, there are janitors, and students don’t clean at all.

ボブ: 本当ですか?私の国では清掃員がいて、生徒は掃除をしません。Jose: In Japan, we have the idea that you should clean up after yourself. It’s something you naturally learn as a child.

ホセ: 日本では「使った場所は自分で片づける」という考えがあって、子どものころから自然に身につくんです。Anisa: Oh, that’s like the saying “Tatsu tori ato o nigosazu”—“Leave no trace behind.”

アニサ: 「立つ鳥跡を濁さず」ですね。Yumi: And even more, the spirit of leaving a place cleaner than when you arrived is what keeps a city beautiful.

ゆみ: さらには、来たときよりもきれいにして立ち去るくらいの心が、街を美しく保ちます。 ”Wrap Up ラップアップ”

”Wrap Up ラップアップ”O-Souji Knowledge

December 13 — The Perfect Day for “Susuharai” (Year-End Cleaning)

12月13日――煤払いに最もふさわしい日

During the Edo period (1603–1868), susuharai (soot cleaning) was held at Edo Castle on December 13. Common people followed this custom and began cleaning their homes on the same day.

江戸時代(1603〜1868年)には、12月13日に江戸城で煤払いが行われ、庶民もこの日に合わせて家の掃除をするようになりました。December 13 was often a Kishuku-nichi (Day of the Resting Spirits), considered one of the most auspicious days in the traditional lunar calendar. It fell about twenty days before the New Year—an ideal time to begin preparations to welcome Toshigami-sama (the New Year deity).

旧暦では、12月13日は「鬼宿日(きしゅくにち)」にあたることが多く、特に縁起の良い日とされていました。旧暦の正月までおよそ20日前という時期で、年神様を迎える準備を始めるのにちょうどよいタイミングでもありました。On this day, people believed that evil spirits stayed quietly inside the house. For that very reason, they cleaned thoroughly—to drive away hidden impurities and purify their homes before the New Year.

この日は、鬼(邪気)が家の中に潜んでいると考えられました。だからこそ、家中を徹底的に掃除して厄を祓い清め、新しい年を迎える準備をしたのです。However, weddings were avoided on this day. Since the home was thought to be filled with spirits being purified, it was considered inauspicious to start a new household.

ただし、この日は婚礼を避ける習わしがありました。家の中にはまだ鬼(穢れ)が残っているとされ、新しい家庭を築くにはふさわしくないと考えられたためです。After cleaning, people in the Edo period would celebrate with great excitement, tossing one another into the air and drinking sake together—sharing joy in welcoming the purified new year.

掃除を終えた人々は、胴上げをしたり、酒を酌み交わしたりして大いに盛り上がりました。清めを終え、新しい年を迎える喜びを分かち合っていたのでしょう。Through such beliefs, December 13 became established as the sacred day to begin susuharai—the great year-end cleaning that purifies both home and heart before welcoming the New Year.

こうした信仰のもとで、12月13日は家と心を清める「煤払い」、つまり大掃除を始める神聖な日として定着していきました。

This article is from the December 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年12月号より掲載しています。

-

[Japan Savvy – August 2025 Issue]

A Summer Cooled by Ghost Stories

怪談で涼む夏August is known as a time of intense heat. During this time in Japan, people enjoy scary stories, tests of courage, and haunted houses.

8月といえば、暑さが厳しい季節。日本ではこの時期、怪談や肝試し、お化け屋敷など、怖い話で盛り上がります。

As the phrase “It sends a chill down your spine” suggests, one reason is that fear can make people feel cool. But it is also said that the background of ghost stories becoming a summer tradition is connected to obon and kabuki.

「背筋が寒くなる」という言葉の通り、恐怖で涼しく感じることも理由の一つですが、怪談が夏の風物詩となった背景には、お盆と歌舞伎が関係しているともいわれています。

In kabuki theaters where the heat caused a drop in audience numbers, it was the remaining young actors who came up with ghost stories as a way to entertain the audience.

暑さで客足が減ってしまう歌舞伎小屋で、残された若手の役者たちがどうにかして客を楽しませようと考えたのが、怪談でした。

It was also believed that during obon, the spirits of ancestors return, which made ghost stories a good match.

また、お盆にはご先祖様の魂が帰ってくると信じられており、怪談との相性がよかったのです。

In the Edo period, “One Hundred Ghost Stories” became popular. On summer nights, one hundred candles were lit, and one candle was extinguished for each ghost story told. It was said that when the last candle went out, something mysterious would happen.

江戸時代には「百物語」が流行しました。夏の夜に百本の蝋燭を灯し、怪談を一話語るごとに一本ずつ消していきます。最後の一本が消えると怪異が起こるとされていました。

Scary, yet somehow captivating — the world of ghost stories brings a coolness to Japanese summer.

怖いけれど、どこか心を惹きつける――。そんな怪談の世界が、日本の夏に涼を届けてくれます。

”Warm Up ウォームアップ”

”Warm Up ウォームアップ”Kaidan JapaNEEDS

Useful words

- 怪談(かいだん)-ghost story

- 肝試し(きもだめし)-test of courage

- お化け屋敷(おばけやしき)-haunted house

- 怖い(こわい)-scary

- 背筋(せすじ)-spine

- 若手(わかて)-young member

- ご先祖様(ごせんぞさま)-ancestors

- 魂(たましい)-soul, spirit

- 相性(あいしょう)-compatibility

- 蝋燭(ろうそく)-candle

- 怪異(かいい)-mystery

- 涼(りょう)-coolness

- 届ける(とどける)-deliver

Ice Breaker Questions

Do you like scary stories?

怖い話が好きですか?

What kinds of yokai (Japanese monsters) do you know?

どんな妖怪を知っていますか?

If you were to take part in a “Hyaku Monogatari” (One Hundred Ghost Stories), what kind of story would you tell?

もし「百物語」をするとしたら、どんな話しをしますか?

What are the traditions of summer in your country?

あなたの国の夏の風物詩は何ですか?

What do you do to get through the hot summer?

暑い夏を乗り越えるために、どんな工夫をしていますか?

”Work Up ワークアップ”

”Work Up ワークアップ”Kaidan Discussion

José: Japanese ghost stories often feature all kinds of yokai.

ホセ:日本の怖い話には、いろいろな妖怪が出てきますよね。

Mayumi: Have you heard of the “Three Great Yokai of Japan”?

まゆみ:「日本三大妖怪」って知っていますか?

Vanessa: That’s the oni, the kappa, and the tengu!

ヴァネッサ:鬼と河童と天狗ですね!

Tim: The kappa lives in rivers and pulls people into the water, doesn’t it?

ティム:河童は川にいて、人を水の中に引き込む妖怪ですよね?

José: It’s scary how all these yokai feel like they could actually be nearby!

ホセ:なんだか、どの妖怪も身近にいそうな感じがして怖いですね!

Mayumi: In the past, people tried to explain mysterious things or disasters that happened around them—things beyond human control—by using yokai.

まゆみ:昔の人は、身近で起こる不思議なことや災害など、人の力ではどうにもできないことを、妖怪を使って説明しようとしたんですよ。

Vanessa: That’s why they feel so familiar in everyday life! But I also heard that yokai aren’t just scary—they have lessons behind them, too.

ヴァネッサ:だから、生活に溶け込んでいるんですね!でも妖怪は怖いだけじゃなくて、教訓があるとも聞きました。

Tim: I see! So maybe the kappa carries the message, “Be careful when playing by the river.”

ティム:なるほど!そしたら河童には「川で遊ぶときは気をつけよう」というメッセージがあると思います。

Mayumi: Exactly. Yokai were also used to “discipline” and “teach” children. Like, “If you stay up too late or tell lies, a scary yokai will come.”

まゆみ:そうなんです。妖怪は、子どもへの「しつけ」や「教え」にも使われていたんですよ。夜更かししたり、嘘をついたりすると怖い妖怪が出る…みたいに。

José: Giving a name to something you can’t see and imagining what it looks like—that’s amazing, isn’t it?

ホセ:見えないものに名前をつけて、姿を想像するって、すごいことですよね。

Mayumi: I think that’s also related to the animistic way of thinking in Japan. Since ancient times, it has been believed that even nature and things have souls.

まゆみ:それは、日本のアニミズムの考え方も関係していると思います。日本では、古代より、自然や物にも魂があると考えられてきたんですよ。

Vanessa: And nowadays, yokai have become characters and everyone loves them! A lot of them have cute designs, so they feel even more familiar!

ヴァネッサ:今では、妖怪がキャラクターになって、みんなに親しまれていますよね。かわいいデザインも多くて、もっと身近に感じます!

”Wrap Up ラップアップ”

”Wrap Up ラップアップ”Kaidan Knowledge

Tengu is known as one of the “Three Great Yokai” of Japan, but it is not just a being to be feared. It is also revered as a “mountain god.”

天狗は「日本三大妖怪」の一つとして知られていますが、ただ恐れられる存在ではありません。「山の神」としてあがめられることもあります。

As for the “Three Great Evil Yokai of Japan,” they are Shutendoji the oni, Tamamonomae the nine-tailed fox, and Emperor Sutoku, who is said to have died in anger and sadness and become a vengeful spirit.

「日本三大悪妖怪」といえば、鬼の酒呑童子、九尾狐の玉藻前、そして怒りや悲しみの中で亡くなり、怨霊になったとされる祟徳天皇です。

Even in Kojiki, Japan’s oldest historical book, yokai such as oni and Yamata-no-Orochi already appear.

日本最古の歴史書『古事記』でも、すでに鬼やヤマタノオロチなどの妖怪が登場しています。

In the Edo period, yokai were already enjoyed as characters. Many works were created, such as “The Ghost of Oiwa, from the One Hundred Ghost Stories” by Katsushika Hokusai, which attracted people’s interest.

江戸時代には、すでに妖怪がキャラクターとして楽しまれていました。葛飾北斎の「百物語 お岩さん」など、多くの作品が描かれ、人々を惹きつけました。

In the Showa era, “GeGeGe no Kitaro” sparked a yokai boom. Its creator, Shigeru Mizuki, said that when he was a child, he heard many yokai stories from a local elderly woman who knew a lot about superstitions and regional folklore.

昭和に入ると、『ゲゲゲの鬼太郎』が妖怪ブームを巻き起こしました。作者の水木しげるは、子どもの頃、迷信や地元の言い伝えに詳しい近所のおばあさんから、たくさんの妖怪の話を聞いたといいます。

Modern yokai, born in schools and cities, such as Hanako-san of the Toilet and the Slit-Mouthed Woman, are also popular.

「トイレの花子さん」や「口裂け女」など、学校や街の中で生まれた「現代の妖怪」も人気です。

In recent years, “Amabie” gained attention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Amabie is a yokai that predicts good harvests and epidemics. Amabie told people “If an epidemic breaks out, make a picture that copies my appearance and show it to others,” and then disappeared.

近年では、コロナ禍に「アマビエ」が注目を集めました。アマビエは、豊作や疫病を予言する妖怪で、疫病が流行ったら自分の姿を書き写した絵を人々に見せるように告げて去っていきました。

“Hoichi the Earless” is one of the most famous ghost stories. Hoichi, possessed by spirits, had sutras written all over his body to protect himself, but his ears were left unwritten—so in the end, his ears were torn off.

「耳なし芳一」は有名な怪談のひとつです。霊に取り憑かれた芳一は、全身にお経を書いてもらって身を守ろうとしますが、耳だけ書き忘れてしまい、最後は耳をちぎられてしまいます。

This article is from the August 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年8月号より掲載しています。

-

[Japan Savvy – November 2025 Issue]

“Food of the Gods” – Kaki Reflecting the Autumn of Japan

「神の食べ物」 ― 柿が映す日本の秋

When we think of fruits that are essential to the autumn landscape, kaki (Japanese persimmons) come to mind.

秋の風景に欠かせない果物といえば、柿です。

Seeds have been found in ruins from the Jomon period (about 14,000 years ago), and kaki have been loved by the Japanese since ancient times.

縄文時代(約1万4千年前) の遺跡からも種が見つかり、古代から日本人に親しまれてきました。

Relatives of kaki are also found in Europe, and its scientific name, Diospyros, means “food of the gods.”

柿の仲間はヨーロッパにもあり、学名 Diospyros は「神の食物」を意味します。

The kaki tree not only bears highly nutritious fruit but has also been used for piano keys and luxury furniture.

柿の木は、滋養豊かな果実を実らせるだけでなく、ピアノの鍵盤や高級家具に使われてきました。

Its common name is persimmon. Its hard wood was even once used to make golf club heads.

一般的な呼び名は persimmon。その堅い木材は、かつてゴルフクラブのヘッドにも用いられました。

In the 19th century, during the Edo period, the Japanese persimmon was newly added to this “food of the gods” family.

19世紀の江戸時代になると、この「神の食物」の仲間に、日本の柿が新たに加わりました。

Its scientific name became Diospyros kaki. The Japanese word “kaki” was incorporated as it is into the genus name “food of the gods.”

学名は Diospyros kaki。属名の「神の食物」に日本語の「kaki」がそのまま組み込まれました。

Kaki is so rich in nutrients that there is a saying, ‘When kaki turn red, doctors turn pale.'”

「柿が赤くなれば医者は青くなる」と言われるほど栄養満点の柿。

Truly, it is the “food of the gods” that reflects the autumn of Japan.

まさに日本の秋を映す「神の食物」です。

”Warm Up ウォームアップ”

”Warm Up ウォームアップ”kaki JapaNEEDS

Useful words

- 柿(かき)-Japanese persimmon

- 遺跡(いせき)-ruin

- 種(たね)-seed

- 食物 / 食べ物(しょくもつ / たべもの)-food

- 滋養 (じよう)-nourishment

- 豊か(ゆたか)-rich, abundant

- 果実(かじつ)-fruit

- 高級(こうきゅう)-luxury, high-class

- 家具(かぐ)-furniture

- 一般的(いっぱんてき)-general

- 堅い(かたい)-hard, firm

- 栄養満点(えいようまんてん)-nutritious

- 映す(うつす)-reflect

Ice Breaker QuestionsHave you ever eaten a persimmon? What did it taste like?

柿を食べたことがありますか?どんな味でしたか?Besides persimmon, what other kinds of wood do you know?

柿の他に、どんな種類の木材を知っていますか?How much do fruits usually cost in your country?

あなたの国では、果物はどのぐらいの値段ですか?When you think of foods that are full of nutrients, what comes to mind?

栄養満点の食べ物といえば、何が思いつきますか?Do you ever feel the “season” through the foods you eat?

食べ物から「季節」を感じることはありますか? ”Work Up ワークアップ”

”Work Up ワークアップ”kaki Discussion

Vanessa: Have you ever heard the saying “Momo kuri sannen kaki hachinen” (“Three years for peaches and chestnuts, eight for Japanese persimmons”)?

ヴァネッサ: 「桃栗三年柿八年」って聞いたことありますか?

Jose: Hmm, I know peaches, chestnuts, and kaki (Japanese persimmons) are all autumn foods, but…

ホセ:うーん、桃も栗も柿も秋が旬の食べ物だとは思うけど…。

Will: Oh! Maybe it means how many years it takes from planting the seed until the fruit grows?

ウィル:あ、もしかして、種を植えてから実ができるまでの年数を表してるんですか?

Mayumi: That’s right! Because it takes time for them to bear fruit, the phrase came to mean that “everything takes time before you see results.”

まゆみ:そうなんです!実るまで時間がかかることから、「何事も成果が出るまで時間が必要」という意味になったんですよ。

Vanessa: Kaki must be really familiar to Japanese people if there’s even a proverb about them.

ヴァネッサ:ことわざにまでなるくらい、柿は日本人にとって身近なんですね。

Mayumi: Yes, they’re often planted in gardens in Japan.

まゆみ:日本では、庭にもよく植えられていますね。

Jose: Speaking of that, I saw news about bears coming down from the mountains and eating kaki in people’s gardens.

ホセ:そういえば、熊が山から降りてきて、庭の柿を食べているニュースを見ました。

Will: There have been a lot of bear attacks recently.

ウィル:最近、熊による被害が多いですね。

Mayumi: Maybe it’s because there’s less food in the mountains.

まゆみ:山に食べ物が少なくなっているのかもしれません。

Will: Do you think deforestation is part of the problem?

ウィル:森林伐採が関係してるんでしょうか?

Vanessa: On top of that, solar panels are being installed all over mountain slopes in Japan, which has become a cause for concern.

ヴァネッサ:それに加えて、日本では山の斜面に太陽光パネルが敷き詰められ、問題視されています。

Jose: What if we planted lots of kaki trees in the mountains?

ホセ:山にたくさんの柿の木を植えるのはどうですか?

Mayumi: That’s a good idea! But remember, it takes eight years before kaki bears fruit.

まゆみ:いい考えですね!でも柿が実るまでには八年かかりますよ。

Will: At least peaches and chestnuts only take three!

ウィル:桃と栗なら三年ですね!

Vanessa: Then we’d need to think of other ways to coexist for at least three years.

ヴァネッサ: 少なくとも三年間は他の共生の方法も考えないといけませんね。

”Wrap Up ラップアップ”

”Wrap Up ラップアップ”kaki Knowledge

Just as there is the saying “The sky is high and horses grow fat in autumn,” autumn is a season when the sky is clear and the harvest is plentiful.

「天高く馬肥ゆる秋」という言葉があるように、秋は空が澄み渡り、実りの季節です。

There is a famous haiku about kaki by Masaoka Shiki: “Eat a persimmon and the bell will toll at Horyuji”

柿に関する有名な俳句に、正岡子規が詠んだ「柿くへば 鐘が鳴るなり 法隆寺」があります。

October 26, the date on which Masaoka Shiki is said to have composed this haiku, is now recognized as “Kaki Day.”

正岡子規がこの句を詠んだとされる10月26日は、現在「柿の日」に認定されています。

Kaki is called Japan’s “national fruit” and has long been a part of people’s daily lives.

柿は日本の「国果」とも呼ばれ、古くから人々の暮らしに根付いてきました。

In the past, there were no sweet persimmons like we have today, so people would dry astringent persimmons to make hoshigaki (dried persimmons) and eat them.

昔は現在のような甘柿がなかったので、渋柿を干し柿にして食べていました。

Hoshigaki were an important preserved food for getting through the winter.

干し柿は冬を越すための大切な保存食でした。

The prefecture that produces the most kaki in Japan is Wakayama.

日本で一番柿の生産量が多い県は和歌山県です。

Kaki even appears in folktales. A famous one is “The Crab and the Monkey.” In this story, the monkey hogs the kaki that the crab had grown and injures the crab, but the crab’s children and their friends work together to take revenge on the monkey.

柿は昔話にも登場します。有名なのは「さるかに合戦」。かにが育てた柿をさるが独り占めしてかにを傷つけますが、かにの子どもたちと仲間たちが力を合わせて仕返しをするという物語です。

In recent years, bear attacks have been increasing. 2023 saw the highest number on record, and in 2025 they are continuing at the same level.

近年は、熊の被害が増えています。2023年は過去最多で、2025年も同じ水準で推移しています。

One reason bears are coming into human settlements is that, due to population decline, villages are returning to forest, making the boundary between the bears’ and humans’ living areas less distinct.

熊が人里に出てくる原因には、人口減少で集落が森に戻り、熊と人間の生活圏の境界があいまいになっていることも挙げられます。

This article is from the November 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年11月号より掲載しています。

-

Japan’s Food Culture Living with Microorganisms —Flavors and Traditions Nurtured by Fermentation

- Hiragana Times

- Oct 15, 2025

[Japan Savvy – October 2025 Issue]

Japan’s Food Culture Living with Microorganisms

—Flavors and Traditions Nurtured by Fermentation

菌と生きる日本の食文化 ― 発酵が育む味と伝統Speaking of autumn, it is the season of harvest. Overcoming the heat, various crops reach their peak of harvesting.

秋といえば、実りの季節。暑さを乗り越えて、様々な作物が収穫のピークを迎えます。

In the era without refrigerators, the Japanese devised many ways to preserve these precious harvests for a long time.

冷蔵庫のない時代、この貴重な収穫物を長期保存するために、日本では様々な工夫がされてきました。

The representative among them is “fermentation.” By using the power of microorganisms to preserve and transform ingredients, people created unique fermented foods such as miso, soy sauce, and natto.

その代表格が「発酵」です。菌の力で食材を保存・変化させ、味噌や醤油、納豆といった独自の発酵食品を生み出しました。

Japanese fermentation culture goes back to the Jomon period, and it is said that people at that time preserved nuts and fish by salting them.

日本の発酵文化は縄文時代までさかのぼり、当時の人々は木の実や魚を塩漬けにして保存していたと伝えられています。

Sushi, a representative of Japanese food, also began when the technique of fermenting fish with rice was introduced along with rice cultivation.

日本食の代表・寿司も、魚を米と発酵させる技法が稲作とともに伝わったことに始まります。

The humid climate of Japan accepted this technique and became soil that further nurtured fermentation culture.

湿度の高い日本の風土は、この技法を受け入れ、発酵文化をさらに育む土壌となったのです。

The people of ancient times may have been making use of the mysterious power of microorganisms in their lives, while conversing with them.

古代の人々は、菌と対話しながら、その神秘的な力を暮らしに生かしていたのかもしれません。

”Warm Up ウォームアップ”

”Warm Up ウォームアップ”hakko JapaNEEDS

Useful words- 実り(みのり)-harvest, fruitful

- 乗り越える(のりこえる)-overcome

- 冷蔵庫(れいぞうこ)-refrigerator

- 保存(ほぞん)-preserve, keep

- 発酵(はっこう)-fermentation

- 菌(きん)-microorganisms, bacteria

- 塩漬け(しおづけ)-pickling in salt

- 湿度(しつど)-humidity

- 風土(ふうど)-climate

- 土壌(どじょう)-soil

- 古代(こだい)-ancient times

- 対話(たいわ)-dialogue, conversation

- 神秘的(しんぴてき)-mysterious

Ice Breaker Questions

What is your favorite Japanese food? Please also tell us the reason.

好きな日本の食べ物は何ですか?理由も教えてください。

Speaking of fermented foods, what comes to your mind?

発酵食品といえば、何を思い浮かべますか?

What kinds of fermented foods are there in your country?

あなたの国の発酵食品にはどんなものがありますか?

If you were to make fermented food yourself, what would you like to try?

もし自分で発酵食品を作るとしたら、何に挑戦してみたいですか?

When you eat fermented foods, what effects do you think they have on the body and health?

発酵食品を食べると、体や健康にどんな効果があると思いますか?

”Work Up ワークアップ”

”Work Up ワークアップ”hakko Discussion

Vanessa: Japanese food really does have a healthy image, doesn’t it?

ヴァネッサ:日本食って、やっぱり健康的なイメージがありますよね。

Will: Especially natto! It seems that in the Jomon period too, they ate something like natto.

ウィル:特に納豆!縄文時代にも納豆みたいなものを食べてたらしいですよ。

Jose: Really? That stickiness existed since ancient times?

ホセ:本当ですか?あのネバネバ、古代からあったんですか!

Mayumi: That stickiness comes from natto bacteria. In the human intestine, there are tens of trillions of other bacteria that keep us healthy.

まゆみ:そのネバネバは納豆菌。人間の腸内には、他にも何十兆もの菌がいて、私たちの健康を保っているんですよ。

Vanessa: That many!? Then our bodies are like a “planet” of bacteria?

ヴァネッサ:そんなに!?じゃあ私たちの体って、菌たちの「惑星」みたいなもの?

Will: And bacteria were on Earth long before humans. Depending on how you think, maybe humans exist for the sake of bacteria.

ウィル:しかも菌は人間よりずっと前から地球にいたんです。考えようによっては、人間のほうが菌のために存在してるのかもしれませんね。

Jose: People in the old days must have felt that firsthand and lived while respecting the power of bacteria.

ホセ:昔の人はそれを肌で感じて、菌の力を尊びながら生きてきたんでしょうね。

Mayumi: In Japan, by borrowing the power of bacteria, they made miso, soy sauce, and pickles, and by eating them, they gave “food” to the bacteria inside the body. Koji mold was even designated the “national fungus” in 2006.

まゆみ:日本では、菌の力を借りて味噌や醤油、漬物を作り、それを食べることで体内の菌に「餌」を与えてきたんです。麹菌なんて2006年には「国菌」に認定されましたよ。

Vanessa: Not a national treasure, but a national fungus!

ヴァネッサ:国宝ならぬ国菌!ですね(笑)

Will: Modern people… even though it’s the same “kin,” they only think about “金 (gold).”

ウィル:現代人は…同じ「キン」でも「金」のほうばかり考えてますね。

Jose: Hahaha! And the “kin” in the wallet doesn’t grow at all!

ホセ:あはは!しかも財布の「キン」は全然育たない(笑)

”Wrap Up ラップアップ”

”Wrap Up ラップアップ”hakko Knowledge

Fermented foods are the wisdom of preservation in the era without refrigerators, and they also enhance nutrition and umami.

発酵食品は、冷蔵庫のない時代の保存の知恵であり、栄養やうま味も高めてくれます。

It is said that sake had already been made since the Yayoi period, but the oldest record is from the Nara period, describing “sake made from koji =mold grown on rice.”

日本酒は弥生時代から造られていたとされますが、奈良時代の記録にある「ご飯に生えたカビ=麹で造った酒」が最古の記録です。

In the Edo period, fermentation techniqu

es advanced, the method of making sake close to today’s form was established, and soy sauce and miso also spread to the tables of ordinary people.

江戸時代には発酵技術が進み、今に近い日本酒の製法が整うとともに、醤油や味噌も庶民の食卓に広がりました。

Among dried bonito, known as the hardest food in the world, the highest grade “honkarebushi” is a fermented food.

世界一かたい食品として知られる鰹節の中でも、最高級の「本枯節」は発酵食品です。

Soy sauce, miso, and vinegar are called the “three great fermented seasonings.”

醤油・味噌・お酢は「三大発酵調味料」と呼ばれています。

For the main player of fermentation, “koji,” there are both “麹”, and the unique Japanese character “糀” named because the white hyphae on rice look like flowers.

発酵の主役「こうじ」には「麹

」と日本独自の字「糀」があり、米に白い菌糸が花のように見えることから名付けられました。

Fermentation reflects the climate of the land and created unique flavors in each region, such as Akita’s “iburigakko,” Tokyo’s “kusaya,” and Ibaraki’s “Mito natto.”

発酵は土地の風土を映し取り、秋田の「いぶりがっこ」、東京の「くさや」、茨城の「水戸納豆」など、地域ごとの独自の味を生みました。

Miso also differs by region, with rice miso, barley miso, and soybean miso, and further differences such as sweet or salty taste.

味噌も地域ごとに米味噌・麦味噌・豆味噌があり、さらに甘口や辛口といった味の違いがあります。

Today, with the rise of health consciousness, more people are making fermented foods themselves, such as miso and nukazuke.

現在、健康志向の高まりから、味噌やぬか漬けなど発酵食品を自分で手作りする人も増えています。

This article is from the October 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年10月号より掲載しています。

-

Kinoko and the Japanese People — A Relationship Nurtured by the Forest

きのこと日本人――森に育まれた関係

As a quintessential “taste of autumn,” kinoko (mushrooms) have long been an essential part of Japanese tables.

「秋の味覚」を代表するきのこは、古くから日本の食卓に欠かせない存在です。

The origin of the word “kinoko” is said to be “ki no kodomo (child of a tree),” and it was named so because it grows near trees.

「きのこ」という言葉は「木の子ども」が語源で、木のそばに生えることから名付けられたといわれています。

The main body of kinoko is actually the thread-like structure called “kinshi (hypha)” that spreads underground.

きのこの本体は、実は地中に広がる「菌糸」と呼ばれる糸のような構造です。

Kinshi connects with tree roots and plays the role of a network that links plants in the forest by exchanging nutrients.

菌糸は木の根とつながり、栄養をやり取りしながら森の植物を結ぶネットワークの役割を果たしています。

In recent years, kinshi has been called the “internet of the forest” and has attracted attention as a presence that connects the lives that live in the forest.

近年、菌糸は「森のインターネット」とも呼ばれ、森に生きる命をつなぐ存在として注目されています。

Matsutake, shiitake, eringi (king trumpet,) and maitake—what we see as “kinoko” are the presence like the “fruit” that kinshi sends up above ground.

松茸、椎茸、エリンギ、舞茸など、私たちが目にする「きのこ」は、菌糸が地上に出した「果実」のような存在です。

In Japan, kinoko are said to have already been eaten during the Jomon period.

日本では、縄文時代にはすでに食されていたと言われるきのこ。

The taste of the Jomon people, who lived with nature in forests where kinshi spread, has been passed down to us today.

菌糸が広がる森で自然と共に暮らした縄文人の味覚は、今も私たちに受け継がれています。

Warm Up ウォームアップ” Kinoko JapaNEEDS

Useful words

- 秋(あき)-autumn

- 味覚(みかく)-taste

- きのこ -mushroom

- 食卓(しょくたく)-table

- 語源(ごげん)-origin of a word

- 生える(はえる)-grow

- 菌糸(きんし)-hypha

- 根(ね)-root

- 森(もり)-forest

- つなぐ -connect

- 地上(ちじょう)-above ground

- 広がる(ひろがる)-spread

- 自然(しぜん)-nature

Ice Breaker Questions

What do you feel like eating when autumn comes?

秋になると、何が食べたくなりますか?

What kinds of kinoko do you often see in your country?

あなたの国では、どんなきのこをよく見かけますか?

What’s your favorite kinoko dish?

好きなきのこ料理は何ですか?

What kind of activities come to mind when you think of autumn?

秋のアクティビティといえば、何が思い浮かびますか?

What kind of “autumn of 〇〇” would you like to have this year? (For example, an “autumn of reading”)

今年の秋は、どんな「〇〇の秋」にしたいですか?(例えば「読書の秋」など)

”Work Up ワークアップ” Kinoko Discussion

Bob: Kinoko often appear in games and movies, don’t they?

ボブ:きのこって、ゲームや映画にもよく出てきますよね。

Louise: Like the kinoko in Super Mario Bros.—the one that makes you grow!

ルイーズ:スーパーマリオブラザーズの食べると大きくなるきのこ!

Ari: That one’s actually based on a poisonous mushroom, right? It’s called fly agaric. It looks cute, but…

アリ:あれ、実は毒きのこがモデルなんですよね?ベニテングタケっていう。見た目はかわいいけど。

Yumi: It’s interesting how it became “a symbol of gaining power.”

ゆみ:それが「力を得る象徴」になっているのが面白いですよね。

Bob: In Alice in Wonderland, Alice eats a kinoko to change her size, too.

ボブ:『不思議の国のアリス』でも、アリスがきのこを食べて体のサイズを変えますよね。

Louise: Kinoko is like a symbol of “change.” They feel like something that exists between dreams and reality.

ルイーズ:きのこって、「変化」のシンボルみたい。現実と夢のあいだにいるような存在というか。

Ari: Even in Ghibli films, you see spores floating in the Sea of Decay.—Kinoko really aren’t just ordinary things, are they?

アリ:ジブリでも腐海の森に胞子が舞ってたり、きのこって「ただ者じゃない」ですね。

Yumi: Actually, kinoko are said to have appeared on land earlier than any other plant, and they’ve been living with Earth long before humans.

ゆみ:実は、きのこはどの植物よりも早く地上に現れ、人類よりずっと前から地球と共に生きていたそうです。

Louise: And the kinoko we see are just a tiny part that appears above ground.

ルイーズ:そして、私たちが目にするきのこって、地上に出たほんの一部なんですね。

Ari: Beneath the ground, kinoko’s “threads of communication” spread out… It’s like mythology.

アリ:地面の下には、きのこの「交信の糸」が広がっている……まるで神話みたい。

Yumi: Kinoko aren’t just food—they’re mysterious beings that hold the memory of Earth.

ゆみ:きのこは、単なる食べ物じゃなくて、地球の記憶を宿した神秘的な存在ですね。

Bob: Kinoko is our “great elders,” and “guardian deity” of the forest.

ボブ:私たち人間の「大先輩」であり、森の「守神」ですね。

”Wrap Up ラップアップ” Kinoko Knowledge

Matsutake grows at the base of Matsu trees (pine, mainly Japanese red pine). It is highly aromatic, difficult to cultivate artificially, and rare, which makes it a luxury food.

松茸は、松の木(主にアカマツ)の根元に生えるきのこです。香り高く、人工栽培が難しく、希少価値が高いため高級食材になっています。

Shiitake grows on Shii trees. It is thick and has a strong umami flavor. When dried, it is often used as dashi (broth) and is essential in Japanese cuisine.

椎茸は、椎(しい)の木に生えるきのこです。肉厚でうま味が強く、干すことで出汁としても使われ、和食に欠かせない存在です。

Enokitake grows on Enoki trees (hackberry). Cultivated ones are thin and white, but wild Enokitake are brown and have open caps.

榎茸は、榎(えのき)の木に生えるきのこです。栽培品は白く細長い姿ですが、自然のものは茶色く傘が開いています。

Maitake grows at the base of broadleaf trees such as beech and mizunara oak. Known for its rich aroma and good texture, its name is said to come from the story that people danced with joy when they found it.

舞茸は、ブナやミズナラなどの広葉樹の根元に生えるきのこです。香りと歯ごたえがよく、見つけた人が嬉しさのあまり舞い上がったことが名前の由来とされています。

Shimeji is said to include the meaning from an old Japanese word “shimijimi to oishii kinoko (deeply flavorful kinoko).” There is also a theory that its name comes from the fact that it grows in shimechi (wetlands).

しめじは、「しみじみとおいしいきのこ」という古語の意味を含んでいたとされるほか、「湿地(しめち)」に生えることから名付けられたという説もあります。

There is a Japanese proverb: “Kaori Matsutake, Aji Shimeji,” meaning that while matsutake excels in aroma, shimeji is superior in taste.

「香り松茸、味しめじ」ということわざがあります。香りの良さでは松茸、味の良さではしめじが優れているという意味です。

Japan ranks second in the world in kinoko production, following China.

日本は、中国に続いてきのこの生産量が世界第2位です。

In terms of domestic production, enoki, bunashimeji, and shiitake are the most produced, in that order. These three types account for about 70% of the total.

国内の生産量では、えのき、ぶなしめじ、しいたけの順に多く、この3種類で全体の約7割を占めています。

October 15 is designated as “Kinoko Day.” This is because many types of kinoko are in season in autumn, when both harvesting and consumption peak.

10月15日は「きのこの日」に制定されています。秋になると多くのきのこが旬を迎え、収穫や消費が盛んになることから生まれました。

The story related to kinoko have appeared not only in “Manyoshu,” but also in “Kokin Wakashu,” and “Konjaku Monogatari.”

きのこに関する話は、『万葉集』だけでなく、『古今和歌集』や『今昔物語』にも登場します。

Shiitake, said to be a favorite of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, began to be cultivated artificially during the Edo period. Until then, it was reportedly more valuable than Matsutake.

豊臣秀吉の好物だった椎茸は、江戸時代に人工栽培が始まったとされています。それまでは、松茸よりも高価だったともいわれています。

Among kyogen, there is a piece titled “Kusabira.” In the story, a man is troubled by kinoko growing in his residence, so he calls a yamabushi (mountain priest) to pray. However, the mushrooms only keep multiplying —a humorous tale.

狂言の演目には「茸[くさびら]」という作品があります。屋敷に茸(きのこ)が生えて困った男が山伏を呼び、祈祷してもらうのですが、かえってきのこがどんどん増えてしまうという物語です。

Hiragana Times September 2025 issue

This article is from the September 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年9月号より掲載しています。

-

Welcoming the New Spring with Setsubun | 節分で迎える新しい春

[Japan Savvy – February 2025 Issue]

February 2nd is Setsubun. The word Setsubun means “dividing the seasons” and originally referred to the day before the seasonal turning points: Risshun (spring), Rikka (summer), Risshuu (autumn), and Rittou (winter).

2月2日は節分です。節分は「季節を分ける」という意味があり、本来は季節の節目である立春、立夏、立秋、立冬の前日を指す言葉です。It is believed that bad things, such as evil spirits and illnesses tend to enter at these seasonal transitions, so various events have been held to prevent them.

このような季節の変わり目は、邪気や病気などの悪いものが入り込みやすいとされており、それを防ぐためにさまざまな行事が行われてきました。Since Risshun, the transition from winter to spring, marks the beginning of the year according to the lunar calendar, the day before Risshun is considered the most important among the four Setsubun.

冬から春へと移り変わる立春は、旧暦では一年の始まりにあたるため、その前日は4回ある節分の中でも特に重要とされています。Today, when people say Setsubun, they refer to this February 2nd and people drive out bad spirits from their homes by throwing beans and eating ehoumaki while facing the year’s lucky direction and making a wish.

現在では、節分と言えばこの2月2日のことを指し、家の中から悪いものを追い出すために豆まきをしたり、その年の縁起の良い方角を向いて願い事をしながら恵方巻きを食べたりします。Although New Year’s Eve is December 31st in today’s calendar, Setsubun is still passed down as an important day to pray for good health and fortune.

今の暦だと、大晦日は12月31日ですが、今でも節分は無病息災や幸運を願う日として大切に受け継がれています。 -

The Power of Mochi: Japanese Tradition Coloring the New Year | 餅の力:新年を彩る日本の伝統

[Japan Savvy – January 2025 Issue]

Mochi, made from glutinous rice and characterized by a chewy texture, is an essential food for the Japanese New Year. In particular, mochi pounding, where family, friends, and community members work together to make mochi, has played an important role in strengthening bonds among people.

もち米から作られ、もちもちとした食感の餅は、日本のお正月に欠かせない食べ物です。特に家族や友人、地域の人々が力を合わせて行う餅つきは、人と人との絆を深める重要な役割を果たしてきました。The kanji for “mochi” (餅) means “baked food made from flour” in Chinese. It is believed that this kanji was adopted for the Yamato kotoba (ancient Japanese language) word “mochi” due to its similar appearance.

「餅」という漢字は、中国語では「小麦粉で作った焼き物」を意味します。見た目が似ていたことから、大和言葉の「もち」にこの漢字が当てられたと考えられます。There are several theories about the origin of the Japanese word “mochi.” One theory suggests that the word “mochiii,” a portable rice dish similar to “hoshiii” (dried rice), that was used as preserved food, eventually evolved into “mochi.”

日本語の「もち」の語源にはいくつかの説があります。保存食としての「干し飯[ほしいひ]」と同じく携帯できる飯である「もちいひ」が「もち」になった説。Another theory is that the word originated from its value as a food that could be stored for a long time, referred to as “nagamochi” (lasting a long time). There is also a theory that it derives from “百道 (mochi),” meaning “a hundred lessons.”

長期間保存でき「長持ち」する食べ物として重宝されたことに由来する説。さらには、「百の教え」という意味の「百道(もち)」に由来するという説まであります。Because mochi is made by layering numerous grains of sacred rice, it has long been cherished as an offering to the gods.

餅は神聖な米を何粒も重ねて作られることから、古くより神様への供え物として大切にされてきました。 -

A Day to Appreciate Labor and the Harvest

勤労と収穫に感謝する日

[Japan Savvy – December 2024 Issue]

There are many public holidays in Japan, and the last one of the year is “Labor Thanksgiving Day” on November 23.

日本には多くの祝日がありますが、1年間で最後の祝日は11月23日の「勤労感謝の日」です。In Christianity, labor is regarded as a punishment imposed on humans, but in Japan, labor has been a virtue since ancient times, and “Labor Thanksgiving Day” is, as the name suggests, a day to honor and appreciate work.

キリスト教において労働は人間に課せられた罰とされていますが、日本では古来、労働は美徳であり、「勤労感謝の日」は名前の通り勤労を尊び感謝する日です。Labor Thanksgiving Day was established in 1948, but this day was originally a holiday called “Niiname-sai.”

1948年に制定された勤労感謝の日ですが、もともとこの日は「新嘗祭[にいなめさい]」という祭日でした。In “Niiname-sai,” the character “新” represents new grains (the grains harvested that year), and “嘗” means a feast, which expresses gratitude by offering new rice and other crops to the gods.

新嘗祭の「新」は新穀[しんこく](=その年に取れた穀物)を、「嘗」はごちそうを意味していて、新米などを神様にお供えし、感謝を表します。Rituals of Niiname-sai are held at shrines throughout Japan, and the Emperor, the “Saishi-ou,” who is at the pinnacle of the priesthood, offers the new grain he has grown himself and performs the strenuous task of praying throughout the night for a bountiful harvest and the peace of the people.

新嘗祭の儀式は全国の神社で行われますが、その神職の頂点である祭祀王[さいしおう]である天皇は、自ら育てた新穀を供え、五穀豊穣と国民の安寧を夜通し祈るという激務を果たします。

Information From Hiragana Times

-

February 2026 Issue

January 21, 2026

February 2026 Issue

January 21, 2026 -

January 2026 Issue – Available as a Back Issue

January 15, 2026

January 2026 Issue – Available as a Back Issue

January 15, 2026 -

December 2025 Issue —Available as a Back Issue

November 20, 2025

December 2025 Issue —Available as a Back Issue

November 20, 2025