-

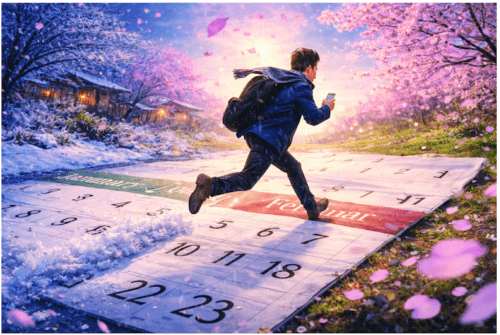

Seasonal Voice-Word Art: “January slips away, February runs away, March goes away” — the early months of the year pass in the blink of an eye.

季節の言技:「一月往ぬる二月逃げる三月去る」― 年のはじめ三か月は、あっという間に過ぎていく。- Hiragana Times

- Jan 28, 2026

[NIHONGO DO – Voice-word Art – February 2026 Issue]

Seasonal Voice-Word Art: “January slips away, February runs away, March goes away” — the early months of the year pass in the blink of an eye.

季節の言技:「一月往ぬる二月逃げる三月去る」― 年のはじめ三か月は、あっという間に過ぎていく。

This “Voice-Word Art” section introduces seasonal words related to the time of year. Enjoy the timeless beauty of these artistic expressions.

この「言技」セクションでは、季節にちなんだ季語を紹介しています。時代を超えて響く言葉のアート(言技)をお楽しみください。

一月往ぬる二月逃げる三月去る

“January slips away, February runs away, March goes away.”

This proverb expresses the sense that the first three months of the year pass with surprising speed. January begins with celebrations, February is short and hurried, and March carries us toward spring. It reminds us that time flows quickly—urging us to savor each moment with care.

年の始まりの三か月は、驚くほど早く過ぎてしまう――そんな季節感を表す言葉です。行事の多い一月、短く慌ただしい二月、そして春へ向かう三月。めまぐるしく過ぎゆく時のなかで、一日一日を大切に生きたいという思いをそっと呼び起こします。

■ Meaning / 意味

Ichigatsu inuru: January “goes away”; the month slips quietly past.

一月 往ぬる:一月はすっと過ぎていく。

Nigatsu nigeru: February “runs away”; short and fast-moving.

二月 逃げる:二月は逃げるように過ぎる。

Sangatsu saru: March “goes away”; carried off toward spring.

三月 去る:三月は春に向かって去っていく。

■ Usage / 使う場面

A: I can’t believe it’s already mid-February.

A: もう二月の半ばなんて信じられないよ。

B: Same here. I haven’t done half the things I planned.

B: 本当。やりたいことの半分もできてない。

A: Well, you know the saying, “January slips away, February runs away, March goes away.”

A: 「一月往ぬる二月逃げる三月去る」って言うじゃない。

B: True… if I don’t move now, spring will be here before I know it.

B: そうだね…。このままだと、気づいたら春になってそう。

This article is from the February 2026 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2026年2月号より掲載しています。

-

Seasonal Voice-Word Art: “When yin reaches its extreme, it turns to yang” — even at the lowest point, signs of improvement will soon appear.

季節の言技:「陰極まれば陽に転ずる」― どん底のときほど、やがて好転の兆しが訪れる。- Hiragana Times

- Dec 25, 2025

[NIHONGO DO – Voice-word Art –January 2026 Issue]

Seasonal Voice-Word Art: “When yin reaches its extreme, it turns to yang” — even at the lowest point, signs of improvement will soon appear.

季節の言技:「陰極まれば陽に転ずる」― どん底のときほど、やがて好転の兆しが訪れる。

This “Voice-Word Art” section introduces seasonal sayings that carry both natural and human wisdom. Enjoy how old phrases fold hope into everyday life.

この「言技」セクションでは、季節に結びついた言葉を通して、自然と人の営みが紡ぐ知恵を紹介します。時代を超えて響く言葉の美をお楽しみください。

“When darkness reaches its limit, it turns to light.” | 陰極まれば陽に転ずる

■ Explanation / 解説

Rooted in classical Chinese thought, the proverb expresses a cyclical view: extremes reverse. In seasonal terms, the deepest cold precedes warmth; in life, the hardest trials can precede recovery. It comforts and reminds us that conditions are not fixed forever.

中国古典の思想に由来するこの言葉は、物事が極まると反転するという循環観を示します。季節なら最も寒い時期の後に暖気が来るように、人生の困難もいずれ好転する――そうした慰めと希望を込めて用いられます。■ Meaning / 意味

- 陰(いん / in) — darkness, passivity, the waning side.

暗やみ、陰の側面。 - 極まれば(きわまれば / kiwamareba) — when it reaches the extreme; the point of culmination.

極限に達したとき。 - 陽(よう / yō) — light, activity, the waxing side.

明るさ、陽の側面。 - 転ずる(てんずる / tennzuru) — to turn, to transform, to reverse.

反転する、変わる。

■ Usage / 使う場面

A: Hey — what’s wrong? Did something happen?

A:どうしたの?何かあったの?

B: I overslept and ran down the station stairs, fell, and to make matters worse my phone broke…

B:寝坊して駅の階段を走って降りたら転んでしまった。しかも、そのときスマホが壊れちゃって…。A: That’s really rotten luck. But good things will come.

A:それは踏んだり蹴ったりだね。でも、いいことあるよ。B: Why do you say that?

B:なんで?

A: You know the saying, “When darkness reaches its limit, it turns to light.” From now on, only good things will happen.

A:「陰極まれば陽に転ずる」って言うじゃない。これからは、いいことしか起こらないよ。

This article is from the January 2026 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2026年1月号より掲載しています。

-

Seasonal Word Leaves: “Shiwasu” — year-end bustle and quiet winter pockets across the islands.

季節の言の葉:日本の12月「師走」— 年の瀬の慌ただしさと、各地に残る静かな冬景色。- Hiragana Times

- Nov 21, 2025

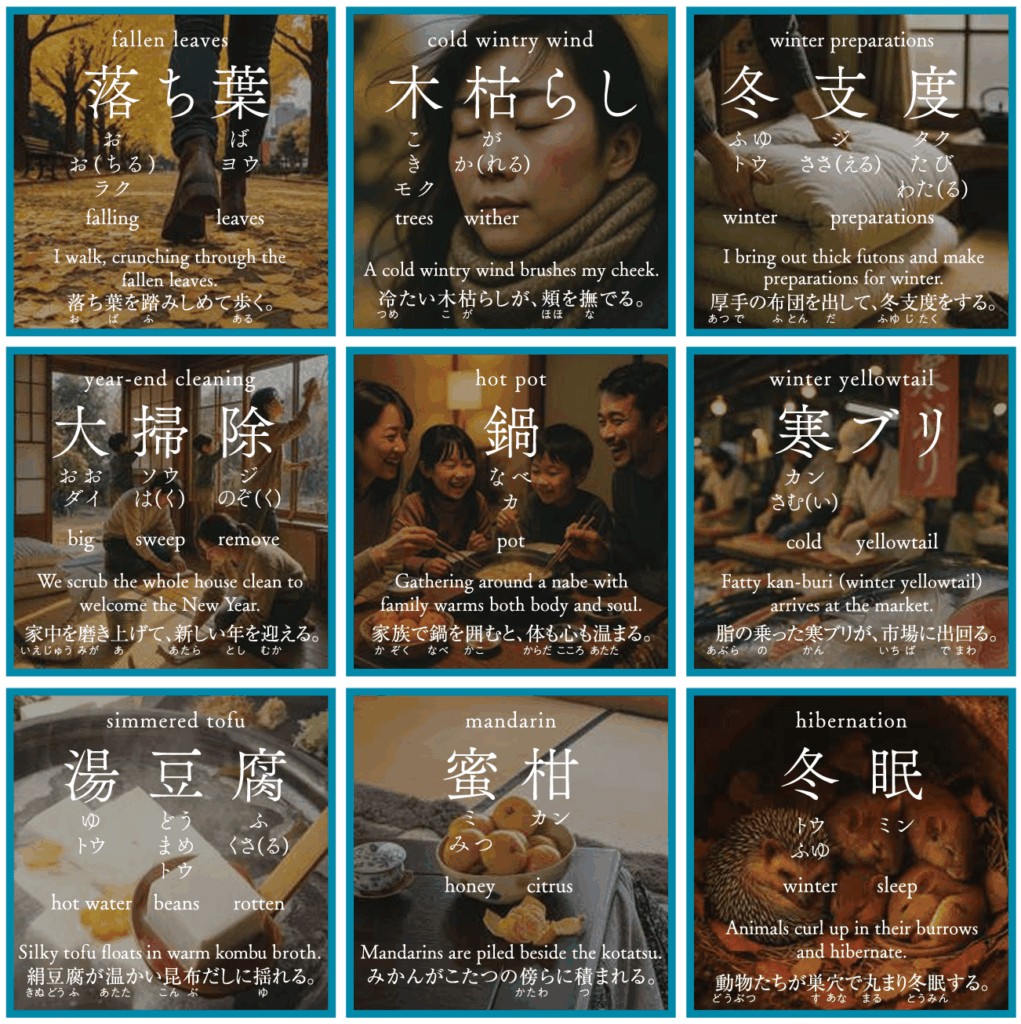

[NIHONGO DO – Word Leave – December 2025 Issue]

Seasonal Word Leaves: “Shiwasu” — year-end bustle and quiet winter pockets across the islands.

季節の言の葉:日本の12月「師走」— 年の瀬の慌ただしさと、各地に残る静かな冬景色。

Shiwasu expresses the bustle of the year’s end. Schedules fill up, gifts are chosen, and the streets grow busy. In some villages the snow arrives and everything falls silent; along the coast, markets brim with winter fish. From year-end cleanings and the exchange of seasonal gifts (oseibo) to steaming nabe and families gathered around the kotatsu — these small vignettes of year-end life are what we collect and share.

師走は年の終わりの慌ただしさを表します。手帳が埋まり、贈り物が選ばれ、街は忙しく動きます。雪に閉ざされ静まる里もあれば、沿岸では寒魚が並ぶ市場もあります。大掃除やお歳暮、湯気立つ鍋、こたつを囲む団らん──年の瀬の暮らしに息づく、そんな日常の断片を拾い集めてお届けします。

This article is from the December 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年12月号より掲載しています。

-

[NIHONGO DO – Voice-word Art – November 2025 Issue]

Seasonal Voice-Word Art: “The fuller the grain, the lower it bows”

季節の言技:実るほど頭を垂れる稲穂かな

This “Voice-Word Art” section introduces seasonal words related to the time of year. Enjoy the timeless beauty of these artistic expressions.

この「言技」セクションでは、季節にちなんだ季語を紹介しています。時代を超えて響く言葉のアート(言技)をお楽しみください。

“The fuller the grain, the lower it bows” | 「実るほど頭を垂れる稲穂かな」

“Minoru hodo, kōbe o tareru, inaho kana” is a proverb that compares a ripe stalk of rice bending under the weight of its grains to a person whose accomplishments bring humility rather than pride. The image is simple and vivid: when rice becomes heavy with grain, the stalks bow low to the earth. Similarly, those who have gained knowledge, skill, or success often show modesty and restraint—true maturity that does not need to boast. The phrase praises quiet dignity and the graceful modesty that accompanies real achievement.

「実るほど頭を垂れる稲穂かな」とは、実り豊かな稲の穂が重さで自然に頭を垂れる様子を、人の成熟と謙虚さにたとえたことわざです。たわわに実った稲は自らの重みでしなり、地面に頭を向けます。人もまた、知恵や力量が深まるほど、むしろ控えめになり、誇示しない謙虚さを示す——そうした内面的な成熟を讃える言葉です。■ Meaning / 意味

Minoru hodo: The more one ripens; figuratively, the more one achieves or matures.

実るほど:成熟したり成果を得るほど、という意味です。

Kōbe o tareru: To bow the head; an image of modesty and deference.

頭を垂れる:謙虚にうなだれる、慎み深く振る舞うさまを表します。

Inaho: A stalk or ear of rice; the concrete image anchoring the proverb.

稲穂:稲の穂。具体的な自然の像が表現の中心です。

Kana: A classical sentence-ending particle that adds a reflective or admiring tone.

かな:感嘆や省察を付け加える古語の終助詞で、味わい深い響きを与えます。■Usage / 使う場面

Sato: You’ve become department head, but you still treat everyone so kindly.

佐藤:課長になったのに、みんなに対して変わらず親切だね。

Suzuki: I learned a lot from my mentors. There’s still much to learn.

鈴木:先輩方から学んだことが多いです。まだまだ勉強中です。

Sato: Truly—the fuller the grain, the lower it bows

佐藤:まさに「実るほど頭を垂れる稲穂かな」だね。—

Sarah: He aced the competition, but he didn’t brag at all.

サラ:彼、コンテストで優勝したのに全然自慢しないんだよ。

Michelle: Right—real skill often comes with quiet humility.

ミシェル:そうね。本当に実力のある人は静かに謙虚なものだよね。

Sarah: It’s like minoru hodo, kōbe o tareru, inaho kana.

サラ:まさに「実るほど頭を垂れる稲穂かな」って感じだね。

This article is from the November 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年11月号より掲載しています。

-

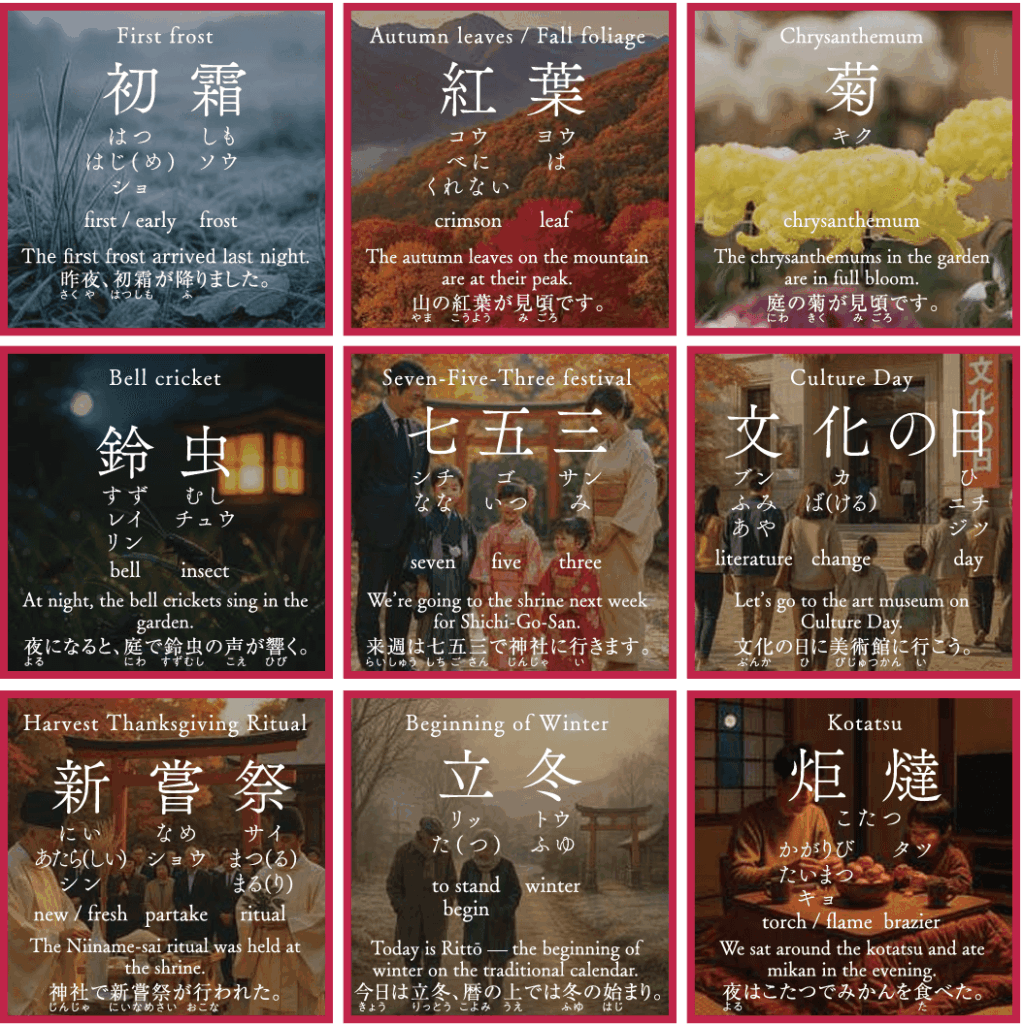

Seasonal Word Leaves: Japan’s November, “Shimotsuki” — The country’s long, changing face from north to south.

- Hiragana Times

- Oct 22, 2025

[NIHONGO DO – Word Leave – November 2025 Issue]

Japan’s November, “Shimotsuki” — The country’s long, changing face from north to south.

日本の11月「霜月」—縦に長い列島が見せる多様な晩秋の表情。

“Shimotsuki” may suggest first frost, but Japan’s long north–south span means the season varies: early frost in the north, harvest’s afterglow and chrysanthemum scent in the south. The name is lunar in origin, and recent climate shifts have widened regional differences. Here we capture local rhythms—harvested fields, autumn foliage, kotatsu preparations—through on-the-ground scenes and local voices.

霜月と聞けば初霜を思い浮かべますが、縦に長い日本では北で早く霜や初雪が降る一方、南ではまだ収穫の余韻と菊の香りが残ります。名は太陰暦に由来して現代暦と一致せず、近年の気候変動で季節感の差も広がっています。刈り取りを終えた田、色づく紅葉、こたつや鍋の支度。各地の移ろいを風景と声で伝えます。

This article is from the November 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年11月号より掲載しています。

-

[NIHONGO DO – Voice-word Art – October 2025 Issue]

Seasonal Voice-Word Art: Taifū Ikka — the clearing after a typhoon

季節の言技:台風一過This “Voice-Word Art” section introduces seasonal words related to the time of year. Enjoy the timeless beauty of these artistic expressions.

この「言技」セクションでは、季節にちなんだ季語を紹介しています。時代を超えて響く言葉のアート(言技)をお楽しみください。

“The clearing after a typhoon” |「台風一過」

“Taifū ikka” literally describes the weather after a typhoon has passed: the heavy clouds and humidity are swept away, leaving clear, bright skies and crisp air. By extension it is used metaphorically when a troubling episode or uproar ends and people feel relieved and refreshed — as if a long storm has finally passed and a new, clearer day begins.

「台風一過」とは、本来は台風が通り過ぎたあとに空が晴れ渡り、さわやかな好天になることを指す表現です。台風一過の空は、厚い雲や湿気が一掃されて、陽光が眩しく、風が澄んで感じられます。転じて、騒動や問題が収束して心が晴れやかになる様子にも使われ、悪い流れが過ぎ去り、新しい一歩を踏み出す比喩として日常でもよく登場します。

■ Meaning / 意味

Taifuu: A powerful tropical cyclone that brings strong winds, heavy rain, and sometimes storm surge and flooding.

台風: 熱帯低気圧が発達した強い暴風雨のこと。大雨や強風、高潮など被害を伴うことが多い。

Ikka: Literally “passing over once” — here meaning that the storm (or trouble) has moved on and been cleared away.

一過: 「一時的に通り過ぎること」。ここでは「(悪天や騒動が)一度通り過ぎていく」という意味合いを表します。

■Usage / 使う場面

Misaki: The rain and wind were awful a little while ago, but look — the sky’s completely blue now.

美咲:まだ4時なのに、もう外が薄暗くなってきたね。

Kenji: Yeah. That’s taifū ikka all right.

健二:本当だね。まさに『秋の日はつるべ落とし』だ。そろそろ家に帰らないと、すぐに真っ暗になっちゃうよ。

Sarah: That project crisis finally wrapped up. Everyone seems so much lighter.

サラ:あのプロジェクトのトラブル、ようやく決着がついたね。みんなほっとしてる感じ。

Michael: Exactly — it feels like taifū ikka: the stress is gone and we can move forward.

マイケル:そうだね。長い不安が消えて、職場の空気も一変したよ。まさに『台風一過』ってやつだ。

This article is from the October 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年10月号より掲載しています。

-

『日本語道(R)』について | About Nihongo-do

- Hiragana Times

- Oct 06, 2025

Japanese is an isolated language born from a ‘Galapagos culture.’

日本語は、「ガラパゴス文化」から生まれた孤立言語。

Japanese is an isolated language that developed independently in an island nation located at the edge of the Eurasian continent. This language, with its unparalleled complexity, can express even the subtlest nuances.

日本語は、ユーラシア大陸の端に位置する島国で独自に発展してきた孤立言語です。その言語は、世界に類を見ない複雑さにより、微妙なニュアンスまで表現できる言語となっています。

Japan, while being an advanced country, has a unique traditional culture woven into daily life. This culture is not only deeply tied to the Japanese language, but it is also no exaggeration to say that the language itself has nurtured the culture.

日本は先進国でありながら、日常生活にユニークな伝統文化が息づいています。そして、この文化は日本語と深く結びついているだけでなく、日本語そのものが文化を育んでいるといっても過言ではありません。

In recent years, many earthenware artifacts dating back around 15,000 years have been discovered in Japan, archaeologically proving that civilization existed at that time. This has led to the perspective that Japan should be classified as an “isolated civilization,” distinct from Chinese civilization.

近年、日本では1万5千年前後の土器が多く見つかり、当時から文明が存在していたことが考古学的に証明されました。これにより、日本は中華文明に含まれない「孤立文明」として分類される見方が生まれました。

What is even more intriguing is that no weapons have been found among the excavated items. It is believed that Japan enjoyed over 10,000 years of peace, which may have influenced the character of the Japanese people.

さらに興味深いのは、出土品から武器がまったく発見されていないことです。当時の日本は1万年以上の平和が続いていたと考えられ、それが日本人の性格形成に影響を与えたのではないかと推測されています。

Even in modern Japan, unique cultural practices exist. For example, there are spotless public facilities with no litter, a rich food culture that incorporates dishes from various countries, trains that run on time, elementary school children going to school by themselves, safe streets where people can walk at night, and moral behaviors such as turning in a lost wallet to the police instead of keeping it for oneself.

現代の日本でも、独特な文化が存在します。例えば、ごみのない清潔な公共施設、各国の料理を取り入れた豊かな食文化、時刻通りに走る電車、子どもだけで学校に通う小学生、夜中でも出歩ける治安の良さ、そして、財布を拾っても自分のものにすることなく派出所等に届けるといったモラルある行動などが挙げられます。

Could it be that these cultures and morals have been created, nurtured, and preserved by the Japanese people? We believe that the existence of the Japanese language plays a significant role. Just as a program is installed in a computer, the thoughts and sensibilities of those born and living in Japan are ingrained in them.

こうした文化やモラルが今も失われずにあるのは、いずれも日本人が生み出し、育み、守り続けてきたからでしょうか?私たちは、「日本語」の存在が大きいと考えています。コンピュータにプログラムがインストールされているように、日本という国に生まれ、生きる人々の思考や感覚に組み込まれているのです。

Many tourists who come to Japan from abroad are moved by its food culture and express a desire to live in Japan. We often hear them say that after arriving, they feel their hearts have become calmer, touched by the politeness and courtesy of the Japanese, even when buying something as small as a single juice.

海外から日本にやって来る多くの観光客は、日本の食文化に感動し、日本に住みたいと言います。たった1本のジュースを買う時でさえ丁寧で礼儀正しく対応する日本人に触れ、日本に来てから心が穏やかになったという声もまた、よく聞かれます。

We see the Japanese language, which lies at the foundation of Japanese culture, not merely as a communication tool but as a profound traditional art form, akin to the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, judo, and kendo. This is what we call “Nihongo-do” (The Way of the Japanese Language).

私たちは、日本文化の根底にある日本語を、単なるコミュニケーションツールではなく、茶道や華道、柔道、剣道と同じく、奥深い日本の伝統文化として捉えています。それが「日本語道」です。

Through this Nihongo-do section, we hope to share Japanese culture with people worldwide.

この日本語道のコーナーを通し、世界中の人々と日本文化を分かち合って行きたいと思います。

By stepping into Nihongo-do today, you become a “Nihongo-jin.”

日本語道に足を踏み出すあなたは今日から「日本語人」です。

Let’s begin! | さあ、始めましょう!

Nihongo-do Content | 日本語道コンテンツ

■ 言波 [コトハ / Kotoha ~ Voice Wave]

Even when the same words are spoken, the way they are conveyed changes depending on the atmosphere in which they are expressed. Words seem to have “waves,” like frequencies. Beneath the surface of these waves, there must be something like a heartbeat that creates the waves. This is the “heart,” and in Japan, we call it “Kotodama” (the spirit of words).

同じ言葉を発しても、発する際の雰囲気によって伝わり方が変わります。言葉にはまるで周波数のような「波」が存在しているかのようです。また、「波」が生まれる奥底には、その波を生み出す鼓動のようなものがあるはずです。それが「心」であり、日本ではこれを「コトタマ(言霊)」と呼びます。

■ 言葉 [コトノハ / Kotonoha ~ Voice Leaves]

Words are like leaves on a tree. They are colored by people’s thoughts and emotions, and they are carried to others. The reason the character for “leaf” is used in the word “kotoba” (words) is believed to be connected to the Japanese reverence for nature. Japan’s oldest poetry collection is also titled “Manyoshu” (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves).

言葉はまるで木の葉のようです。人の心や考えに色づけられ、他者へと伝わっていきます。「ことば」に「葉」という漢字を当てた背景には、日本人の自然崇拝が関係していると考えられます。日本最古の歌集も『万葉集』と名付けられています。

■ 言技[コトワザ Kotowaza ~ Voice Art]

The so-called “proverbs” are written as “諺” (kotowaza). Here, however, we will introduce not only proverbs in their traditional sense but also teachings from “The Analects of Confucius,” waka poetry, and even modern expressions, all of which are practical blends of “voice waves” and “voice leaves” in daily life. These words, which foster human sensibilities, are what we call “voice art” (kotowaza).

The so-called “proverbs” are written as “諺” (kotowaza). Here, however, we will introduce not only proverbs in their traditional sense but also teachings from “The Analects of Confucius,” waka poetry, and even modern expressions, all of which are practical blends of “voice waves” and “voice leaves” in daily life. These words, which foster human sensibilities, are what we call “voice art” (kotowaza).いわゆる「ことわざ」は「諺」と書きます。ここでは本来の意味での「諺」にとどまらず、論語、和歌、さらには現代口語表現まで、人々の生活の中で「言波」と「言葉」が自由闊達[かったつ]に融合し実生活に活用され、人々の感性を育てている言葉のアート(言技)として紹介していきます。

-

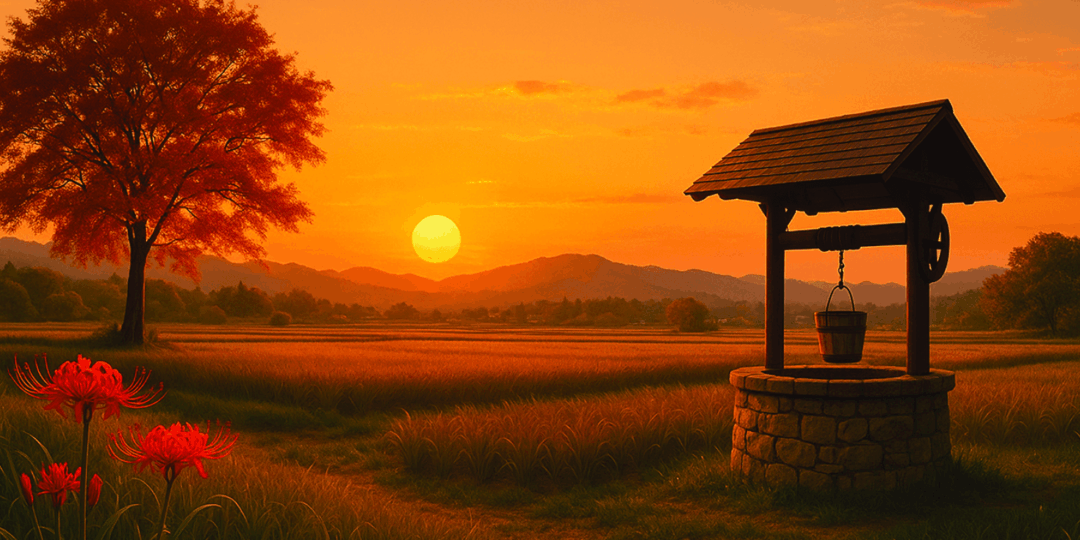

[NIHONGO DO – Voice-word Art – September 2025 Issue]

Seasonal Voice-Word Art: An autumn day drops like a well bucket

季節の言技:秋の日はつるべ落とし

This “Voice-Word Art” section introduces seasonal words related to the time of year. Enjoy the timeless beauty of these artistic expressions.

この「言技」セクションでは、季節にちなんだ季語を紹介しています。時代を超えて響く言葉のアート(言技)をお楽しみください。

“An autumn day drops like a well bucket” |「秋の日はつるべ落とし」

“Aki no hi wa tsurube otoshi” is a proverb that describes how quickly the day ends in autumn, with the sun setting suddenly. It compares this to the way a “tsurube”—a bucket used for drawing water from a well—drops straight and fast. In contrast to the slow, gradual sunsets of summer, it can be surprising in autumn how a sky that was bright just moments before suddenly darkens. The phrase is used not only to describe the early arrival of night but also as a metaphor for how things can come to an abrupt end.

「秋の日はつるべ落とし」とは、秋になると太陽が急に沈み、あっという間に日が暮れる様子を表すことわざです。井戸から水を汲む「つるべ」という桶が、まっすぐ速く落ちる様子に例えています。夏の夕暮れがゆっくりと移り変わるのとは対照的に、秋はさっきまで明るかった空が急に暗くなり驚かされます。この言葉は日暮れの早さだけでなく、物事があっけなく終わる様子の比喩としても使われます。

■ Meaning | 意味

Aki no hi: An autumn day. It especially refers to the time of year when daylight hours are getting shorter.

秋の日: 秋の一日。特に、日照時間が短くなっていく時期を指します。

Tsurube: A bucket attached to a rope or pole, used for drawing water from a well.

つるべ: 井戸の水を汲み上げるために使われる、縄や竿の先につけた桶のこと。

Otoshi: To drop. Here, it refers to the way the bucket falls straight and fast under its own weight.

落とし: 落とすこと。ここでは、つるべが重力に従って、まっすぐに速く落ちる様子を表しています。 Ask

■Usage | 使う場面

Misaki: It’s only 4 o’clock, but it’s already getting dim outside.

美咲:まだ4時なのに、もう外が薄暗くなってきたね。

Kenji: You’re right. It’s a perfect example of ‘aki no hi wa tsurube otoshi.’ If we don’t head home now, it’ll be pitch-black.

健二:本当だね。まさに『秋の日はつるべ落とし』だ。そろそろ家に帰らないと、すぐに真っ暗になっちゃうよ。

Sarah: The weekend barbecue was fun, but it was over in a flash.

サラ:週末のバーベキュー、楽しかったけど、あっという間に終わっちゃったね。

Michelle: I know. Fun times fly by so quickly, just like ‘aki no hi wa tsurube otoshi.’

マイケル:そうだね。楽しい時間は、まるで『秋の日はつるべ落とし』みたいに、すぐに過ぎてしまうものさ。

This article is from the September 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年9月号より掲載しています。

Information From Hiragana Times

-

February 2026 Issue

January 21, 2026

February 2026 Issue

January 21, 2026 -

January 2026 Issue – Available as a Back Issue

January 15, 2026

January 2026 Issue – Available as a Back Issue

January 15, 2026 -

December 2025 Issue —Available as a Back Issue

November 20, 2025

December 2025 Issue —Available as a Back Issue

November 20, 2025