-

『日本語道(R)』について | About Nihongo-do

- Hiragana Times

- Oct 06, 2025

Japanese is an isolated language born from a ‘Galapagos culture.’

日本語は、「ガラパゴス文化」から生まれた孤立言語。

Japanese is an isolated language that developed independently in an island nation located at the edge of the Eurasian continent. This language, with its unparalleled complexity, can express even the subtlest nuances.

日本語は、ユーラシア大陸の端に位置する島国で独自に発展してきた孤立言語です。その言語は、世界に類を見ない複雑さにより、微妙なニュアンスまで表現できる言語となっています。

Japan, while being an advanced country, has a unique traditional culture woven into daily life. This culture is not only deeply tied to the Japanese language, but it is also no exaggeration to say that the language itself has nurtured the culture.

日本は先進国でありながら、日常生活にユニークな伝統文化が息づいています。そして、この文化は日本語と深く結びついているだけでなく、日本語そのものが文化を育んでいるといっても過言ではありません。

In recent years, many earthenware artifacts dating back around 15,000 years have been discovered in Japan, archaeologically proving that civilization existed at that time. This has led to the perspective that Japan should be classified as an “isolated civilization,” distinct from Chinese civilization.

近年、日本では1万5千年前後の土器が多く見つかり、当時から文明が存在していたことが考古学的に証明されました。これにより、日本は中華文明に含まれない「孤立文明」として分類される見方が生まれました。

What is even more intriguing is that no weapons have been found among the excavated items. It is believed that Japan enjoyed over 10,000 years of peace, which may have influenced the character of the Japanese people.

さらに興味深いのは、出土品から武器がまったく発見されていないことです。当時の日本は1万年以上の平和が続いていたと考えられ、それが日本人の性格形成に影響を与えたのではないかと推測されています。

Even in modern Japan, unique cultural practices exist. For example, there are spotless public facilities with no litter, a rich food culture that incorporates dishes from various countries, trains that run on time, elementary school children going to school by themselves, safe streets where people can walk at night, and moral behaviors such as turning in a lost wallet to the police instead of keeping it for oneself.

現代の日本でも、独特な文化が存在します。例えば、ごみのない清潔な公共施設、各国の料理を取り入れた豊かな食文化、時刻通りに走る電車、子どもだけで学校に通う小学生、夜中でも出歩ける治安の良さ、そして、財布を拾っても自分のものにすることなく派出所等に届けるといったモラルある行動などが挙げられます。

Could it be that these cultures and morals have been created, nurtured, and preserved by the Japanese people? We believe that the existence of the Japanese language plays a significant role. Just as a program is installed in a computer, the thoughts and sensibilities of those born and living in Japan are ingrained in them.

こうした文化やモラルが今も失われずにあるのは、いずれも日本人が生み出し、育み、守り続けてきたからでしょうか?私たちは、「日本語」の存在が大きいと考えています。コンピュータにプログラムがインストールされているように、日本という国に生まれ、生きる人々の思考や感覚に組み込まれているのです。

Many tourists who come to Japan from abroad are moved by its food culture and express a desire to live in Japan. We often hear them say that after arriving, they feel their hearts have become calmer, touched by the politeness and courtesy of the Japanese, even when buying something as small as a single juice.

海外から日本にやって来る多くの観光客は、日本の食文化に感動し、日本に住みたいと言います。たった1本のジュースを買う時でさえ丁寧で礼儀正しく対応する日本人に触れ、日本に来てから心が穏やかになったという声もまた、よく聞かれます。

We see the Japanese language, which lies at the foundation of Japanese culture, not merely as a communication tool but as a profound traditional art form, akin to the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, judo, and kendo. This is what we call “Nihongo-do” (The Way of the Japanese Language).

私たちは、日本文化の根底にある日本語を、単なるコミュニケーションツールではなく、茶道や華道、柔道、剣道と同じく、奥深い日本の伝統文化として捉えています。それが「日本語道」です。

Through this Nihongo-do section, we hope to share Japanese culture with people worldwide.

この日本語道のコーナーを通し、世界中の人々と日本文化を分かち合って行きたいと思います。

By stepping into Nihongo-do today, you become a “Nihongo-jin.”

日本語道に足を踏み出すあなたは今日から「日本語人」です。

Let’s begin! | さあ、始めましょう!

Nihongo-do Content | 日本語道コンテンツ

■ 言波 [コトハ / Kotoha ~ Voice Wave]

Even when the same words are spoken, the way they are conveyed changes depending on the atmosphere in which they are expressed. Words seem to have “waves,” like frequencies. Beneath the surface of these waves, there must be something like a heartbeat that creates the waves. This is the “heart,” and in Japan, we call it “Kotodama” (the spirit of words).

同じ言葉を発しても、発する際の雰囲気によって伝わり方が変わります。言葉にはまるで周波数のような「波」が存在しているかのようです。また、「波」が生まれる奥底には、その波を生み出す鼓動のようなものがあるはずです。それが「心」であり、日本ではこれを「コトタマ(言霊)」と呼びます。

■ 言葉 [コトノハ / Kotonoha ~ Voice Leaves]

Words are like leaves on a tree. They are colored by people’s thoughts and emotions, and they are carried to others. The reason the character for “leaf” is used in the word “kotoba” (words) is believed to be connected to the Japanese reverence for nature. Japan’s oldest poetry collection is also titled “Manyoshu” (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves).

言葉はまるで木の葉のようです。人の心や考えに色づけられ、他者へと伝わっていきます。「ことば」に「葉」という漢字を当てた背景には、日本人の自然崇拝が関係していると考えられます。日本最古の歌集も『万葉集』と名付けられています。

■ 言技[コトワザ Kotowaza ~ Voice Art]

The so-called “proverbs” are written as “諺” (kotowaza). Here, however, we will introduce not only proverbs in their traditional sense but also teachings from “The Analects of Confucius,” waka poetry, and even modern expressions, all of which are practical blends of “voice waves” and “voice leaves” in daily life. These words, which foster human sensibilities, are what we call “voice art” (kotowaza).

The so-called “proverbs” are written as “諺” (kotowaza). Here, however, we will introduce not only proverbs in their traditional sense but also teachings from “The Analects of Confucius,” waka poetry, and even modern expressions, all of which are practical blends of “voice waves” and “voice leaves” in daily life. These words, which foster human sensibilities, are what we call “voice art” (kotowaza).いわゆる「ことわざ」は「諺」と書きます。ここでは本来の意味での「諺」にとどまらず、論語、和歌、さらには現代口語表現まで、人々の生活の中で「言波」と「言葉」が自由闊達[かったつ]に融合し実生活に活用され、人々の感性を育てている言葉のアート(言技)として紹介していきます。

-

Tracing the Memory of Sentiment —

The Role of World Languages and Japanese

情感の記憶を辿るーー世界の言語と日本語の役割 [前半]- Hiragana Times

- Oct 15, 2025

Tracing the Memory of Sentiment — The Role of World Languages and Japanese

情感の記憶を辿るーー世界の言語と日本語の役割 [前半]

About 4.6 billion years ago, the Earth was born. Then, roughly 600 million years later, life emerged in the ocean.

46億年前に地球が誕生し、その後約6億年を経て生命が海で誕生しました。

All living creatures, including us humans, share a common origin in this primitive form of life.

私たち人間を含むすべての生物は、この原始生命を共通の起源としています。

While all organisms possess a fundamental “will to survive,” animals were also gifted with “sentiments.”

すべての生物は共通して「生存欲求」を持っていますが、動物にはさらに「情感」が与えられました。

Among them, humans developed this ability most profoundly, leading to a rich capacity for emotional expression.

特に人間はこの情感を高度に発達させ、豊かな感情表現を生み出しました。

Fear, joy, sorrow, and love—these emotions evolved as intuitive tools to help us make survival decisions.

恐怖、喜び、悲しみ、愛情——これらの感情は、生存に必要な判断を直感的に行う力として進化してきました。

Eventually, humans created “logic” to regulate their sentiments and live more efficiently.

人間はやがて、情感を制御し、より効率的に生きるために「論理」を築きました。

Logic brought order and productivity—but when taken too far, it often served self-interest and disrupted harmony.

論理は秩序や効率をもたらしましたが、時として自己都合に偏り、調和を乱すこともありました。

To correct this imbalance, humanity awakened to “ethics” and moral sensibility.

こうした歪みを正すため、人類は「倫理」(道徳心)を芽生えさせました。

Survival instinct, sentiment, logic, and ethics—these four elements can be said to form the foundation of human harmony and progress.

生存欲求、情感、論理、倫理——調和と人類の真の発展には、これら四つが基本的要素だと言えます。

However, over the past 2,000 years of recorded history, the world has largely favored those who suppressed sentiment and prioritized logic.

しかし、人類は有史以来の約2000年間、情感を抑制し論理を発達させた民族が勝利する世界を築いてきました。

As a result, material civilization and science have advanced at an astonishing pace.

その結果として物質文明や科学技術は飛躍的に発展しました。

But at the same time, this imbalance gave rise to tragedies like war—where logic and strategy determine victory, not sentiment.

一方で戦争という悲劇も生み出しました。戦場では情感よりも論理的な戦略・戦術が勝敗を決するからです。

Today, there is no question that English is the most influential language in the world.

現在、世界で最も影響力のある言語は言うまでもなく英語です。

Highly logical in nature, English traces its roots to Proto-Indo-European, the ancestral language of many modern European tongues.

英語は論理性に優れ、「インド・ヨーロッパ祖語(印欧祖語)」を起源としています。

This ancient language is believed to have originated in the grasslands north of the Black Sea and west of the Caspian Sea.

この祖語が生まれたのは、黒海の北、カスピ海の西の草原地帯とされています。

The nomadic people who lived there mastered horses and wheels, and developed strong military power.

そこに暮らしていた遊牧民は馬と車輪を使いこなし、優れた戦闘能力を有していました。

Through conquest and migration, their language spread far and wide, becoming the foundation of many European languages we know today.

彼らの言葉は移動と征服によって広範囲に拡散し、現代のヨーロッパ諸語の源流となりました。

English, French, German, and most other European languages are descended from this Proto-Indo-European origin.

英語をはじめ、フランス語、ドイツ語など、今日のヨーロッパ言語の大半は、この「インド・ヨーロッパ祖語」を起源としています。

In contrast, Japanese is considered an isolated language, not belonging to any known language family.

一方、日本語はどの語族にも属さない「孤立言語」だと言われています。

As an island nation surrounded by sea, Japan remained relatively untouched by foreign invasions for centuries, allowing its people to cultivate a sentiment-rich way of life.

四方を海に囲まれた島国であったため、長らく外敵の侵略を免れ、情感豊かに暮らしてきました。

Even during the Age of Exploration, when Spain and Portugal posed colonial threats, Japan preserved its peaceful society through strong leadership and national seclusion policies.

大航海時代にスペインやポルトガルの脅威が迫った際にも、強力なリーダーシップのもとで鎖国政策を採用し、平穏な暮らしを維持しました。

Thanks to this, the Japanese language maintained a deep connection with nature and human sentiment, preserving a wealth of delicate and nuanced expressions.

その結果、日本語は自然や情感との深い結びつきを保ち、微妙で繊細な表現を豊富に残すことができたのです。

This article is from the December 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年8月号より掲載しています。

-

The World of Words Connected by Those Who Hope [Part 1] | 希望するものたちがつなぐ言葉の世界 (前編)

[Japan Style – March 2025 Issue]

Looking back at human history, conflicts between ethnic groups have continued without end. In the latter half of the 19th century, one person began to wonder: “Could language differences be the cause of misunderstandings and conflicts?” “If people had a common language, wouldn’t it be possible to build an equal and peaceful society?”

人類の歴史を振り返ると、民族間の対立は絶えず続いてきました。19世紀後半、ある人物が「言語の違いが誤解や争いの原因ではないか」「共通の言語を持つことで、平等で平和な社会を築けるのではないか」と考えました。That person was Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof (1859–1917). He was born in Białystok, in northeastern Poland. At the time, this region was under the rule of the Russian Empire and had a complex history with many ethnic groups living together. In this town, which had a population of only about 20,000 people, as many as five or six different languages were spoken in daily life.

その人物こそが、ルドヴィコ・ザメンホフ(Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof, 1859–1917) です。彼はポーランド北東部のビャウィストクで生まれました。当時、この地域はロシア帝国の支配下にあり、多民族が混在する複雑な歴史を持つ土地でした。人口わずか約20,000人の町で、5~6種類もの言語が日常的に使われていたのです。In 1887, Zamenhof published a book under the pen name “Doktoro Esperanto” (Doctor Hoper), rather than using his real name. The book was titled Unua Libro (The First Book of the International Language). What he proposed was a neutral, common language that would transcend ethnic and national borders. Over time, the pen name Esperanto (meaning “one who hopes”) itself became the name of the language.

1887年、ザメンホフは本名ではなく、「Doktoro Esperanto(エスペラント語で希望する医師)」というペンネームで、一冊の本を発表しました。その本の名は「国際語 第一書(Unua Libro)」。彼が提案したのは、民族や国境を超えた中立的な共通言語でした。やがて、「Esperanto(希望する)」というペンネーム自体が、そのまま言語の名前として定着していきます。

Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof

Zamenhof’s ideal was not merely to create an international common language, but rather, he believed that “the very act of learning Esperanto itself would cultivate a desire for peace within people.” Even today, his philosophy lives on, as Esperantists around the world continue to learn the language and deepen their connections. His ideals remain alive, passed down among those who aspire for peace.

ザメンホフの理想は、単に国際共通語を作ることではなく、「エスペラント語を学ぶこと自体が、人々の中に平和を目指す意思を育む」と考えることでした。現在も彼の思想を受け継ぎ、世界各地のエスペランティストたちがこの言語を学び、交流を深めています。その理念は今も息づき、平和を願う人々の間で受け継がれています。Zamenhof had experience as an ophthalmologist and is thought to have valued “regularity” from a scientific perspective. The grammar of Esperanto, which he designed, completely eliminates exceptions and irregular changes, forming a “perfectly regular structure.” This was the result of his goal to create “a language that is fair to everyone and can be learned in the shortest time.”

ザメンホフは眼科医としての経験を持ち、科学的な視点から「規則性」を重視していたことが想像できます。そんな彼が設計したエスペラント語の文法は、例外や不規則変化を一切排除した「完全に規則的な構造」を持っています。これは、「誰にとっても公平で、最短で習得しやすい言語」を目指した結果でした。On the other hand, English, which has now become the world’s common language, is full of exceptions and irregularities. English has many irregularities, such as verb conjugations, plural forms, and inconsistencies in pronunciation, making it almost the opposite of Esperanto. Yet, why did English, with all its irregularities, spread across the world?

一方、今や世界の共通語となった英語は、例外や不規則変化に満ちています。動詞の活用、複数形の変化、発音の不統一など、エスペラント語とは正反対ともいえる「不規則性」が数多く存在します。にもかかわらず、なぜ英語は世界に広まったのでしょうか?Perhaps, from a human perspective, something that includes a certain degree of irregularity feels more natural and easier to get used to than something that is entirely systematic. And it may not be a coincidence that nations with flexible languages were the ones that expanded their influence throughout history.

もしかすると、人間の感覚としても、すべてが整然としているより、ある程度の不規則性を含んだほうが、自然でなじみやすいのかもしれません。そして、そうした柔軟性を持つ言語を操る国が、歴史の中で影響力を広げていったのも、自然な成り行きだったのかも知れません。So, as English spread across the world, when and how did it reach Japan? In this issue, we trace that history. Japan’s first encounter with the English language dates surprisingly far back—to the late Sengoku period, in the year 1600, when the Battle of Sekigahara took place.

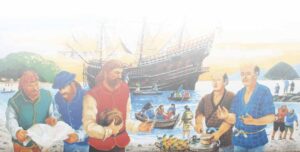

では、英語が世界へ広がる中で、日本にはいつ、どのようにして伝わったのでしょうか? 今回は、その歴史をたどってみました。日本人が初めて英語に触れたのは意外にも古く、戦国時代後期、関ヶ原の戦いが起こった西暦1600年までさかのぼります。That year, a Dutch ship called De Liefde drifted ashore on the coast of Ōita Prefecture. This ship was one of five vessels that had set out from the Netherlands in 1598, aiming for East Asia. At the time, the Netherlands was competing with Portugal and Spain to establish trade routes with Asia, and De Liefde’s voyage was part of that effort.

この年、大分県の海岸に1隻のオランダ船、リーフデ号が漂着しました。この船は、1598年にオランダを出発し、東アジアを目指した5隻の船団のうちの1隻でした。当時のオランダは、ポルトガルやスペインと競いながら、アジアとの貿易路を確立しようとしており、リーフデ号の航海もその一環だったのです。The journey was extremely harsh, and out of the five ships, only De Liefde managed to reach its destination. The crew, which had initially numbered about 110, had been reduced to just 24, finally making landfall in Japan in a state of extreme exhaustion.

航海は過酷を極め、5隻のうち目的地に到達できたのはリーフデ号ただ1隻のみでした。乗組員も当初の約110名からわずか24名にまで減少し、極限状態の中でようやく日本にたどり着いたのです。Among the crew was an English navigator named William Adams. He is said to be the first Englishman ever to set foot in Japan.

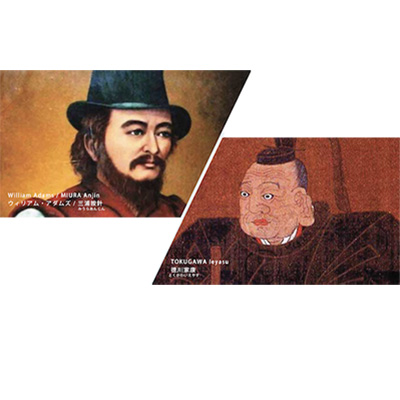

この船には、イギリス人航海士ウィリアム・アダムズが乗船していました。彼こそが、日本に初めて足を踏み入れたイギリス人とされています。

Encounter Drawn by Nobuyuki Tamada (2000)

At the time, the Netherlands was a maritime power, excelling in shipbuilding technology and engaging in trade with countries around the world. Amsterdam was a bustling international commercial hub, a thriving port city where many ships came and went. People dreaming of great fortunes and adventurous sailors eager to explore unknown lands joined Dutch ships, even from neighboring countries, in an attempt to ride the waves of the Age of Exploration.

当時、オランダは造船技術に優れ、世界と交易を行う海洋大国でした。アムステルダムは活気あふれる国際商業の中心地で、多くの船が行き交う港町として栄えていました。一攫千金を夢見る者や、未知の世界に憧れる冒険心あふれる船乗りたちが、周辺国からもオランダ船に乗り込み、大航海時代の波に乗ろうとしていたのです。Adams was one such sailor, but his experiences in Japan were entirely unexpected. After drifting ashore, he was suspected of being a “foreign spy” or even a “pirate” and was held in confinement for some time. This suspicion is believed to have been fueled by Spanish and Portuguese missionaries already in Japan, who had warned the shogunate to be cautious.

そんなオランダ船の乗組員の一人だったアダムズですが、日本での体験はまったくの想定外でした。漂着後、彼は「異国のスパイ」や「海賊」として疑われ、しばらく幽閉されることになります。その背景には、すでに日本に滞在していたスペインやポルトガルの宣教師たちが、幕府に警戒を呼びかけていたともされています。However, Adams’ fate took a dramatic turn when he met Tokugawa Ieyasu. Ieyasu, known for his curiosity, took an interest in Adams’ knowledge and skills and had lengthy discussions with him through an interpreter. Adams explained the political situation in Europe and advised Ieyasu to be particularly wary of the influence of Catholic nations like Portugal and Spain. It is said that this advice later influenced Japan’s policy of national isolation.

しかし、彼の運命を大きく変えたのが、徳川家康との出会いでした。好奇心旺盛な家康は、アダムズの持つ知識と技術に関心を示し、通訳を介してじっくりと話を聞いたとされています。アダムズはヨーロッパの情勢を伝え、特にカトリック国であるポルトガルやスペインの影響力には警戒が必要だと進言しました。この助言は、後の鎖国政策にも影響を与えたとされています。

Ieyasu also recognized Adams’ expertise in navigation and ordered the construction of Japan’s first Western-style sailing ship. Working alongside Japanese craftsmen, Adams helped build an approximately 80-ton ship, and this technology was later applied to the shogunate’s trading vessels, known as shuin-sen (red-seal ships).

また、家康はアダムズの航海技術にも注目し、日本で初めて西洋式帆船を建造させました。アダムズは日本の技術者と協力しながら約80トン級の帆船を完成させ、その技術はのちに幕府の貿易船(朱印船)にも受け継がれていきます。Furthermore, Ieyasu granted Adams samurai status and an estate in the Miura Peninsula (in present-day Kanagawa Prefecture). He was also given the Japanese name “Miura Anjin,” with “Anjin” meaning “navigator”—a reference to his profession.

さらに、家康はアダムズに武士としての身分を与え、三浦半島(現在の神奈川県)に領地を授けました。そして、「三浦按針」という日本名を与えます。「按針」とは航海士を意味する言葉で、その職務に由来しています。Though Adams had no choice but to remain in Japan, he had a wife and children in England and repeatedly requested permission to return home. However, Ieyasu highly valued Adams and would not let him go, leaving Adams’ wish to return home unfulfilled.

その後、日本での生活を余儀なくされたアダムズでしたが、イギリスには妻子がいたため、何度も家康に帰国を願い出ました。しかし、家康は彼を重用し、手放すことはありませんでした。こうして、アダムズの帰国の願いはかなわぬままとなりました。Ironically, in 1613, when the English trading ship Clove arrived in Hirado, Nagasaki, Adams served as an interpreter and successfully facilitated trade negotiations between England and Japan. However, he did not take this opportunity to return home.

皮肉なことに、1613年、イギリスの商船「クローブ号」が長崎県平戸に到着した際、アダムズは通訳として関与し、イギリスとの交易交渉を成功させます。しかし、彼はこれを機に母国へ帰ることはありませんでした。By this time, Adams had already accepted life in Japan, married a Japanese woman, and started a family. He made significant contributions to Japan through his work in interpretation, shipbuilding, and navigation instruction, and later engaged in trade voyages alongside Japanese merchants.

アダムズはすでに日本での生活を受け入れ、日本人の妻を娶り、家庭を築いていました。彼は通訳、造船、航海術の指導を通じて日本に多大な貢献を果たし、さらに日本人商人たちとともに貿易航海にも携わるようになりました。Then, on May 16, 1620, at the age of 55, he passed away in Hirado, Nagasaki. In his will, he specified that his estate should be divided between his families in Japan and England.

そして、1620年5月16日、55歳で長崎県平戸にて生涯を閉じました。彼の遺言には、日本とイギリスの両方の家族に財産を分配することが記されていました。Among the crew of De Liefde was another Dutch navigator, Jan Joosten, who, like Adams, served under Ieyasu. Joosten resided in what is now Tokyo’s Yaesu district, which was named after him.

また、リーフデ号の乗組員には、アダムズ同様に家康に仕え、現在の東京・八重洲(ヤン・ヨーステンの名に由来)に居住していたことで知られるオランダ人航海士ヤン・ヨーステン(Jan Joosten)もいました。After Adams’ death, Japan established a trade system with the Netherlands as its only European trading partner for nearly 200 years. In 1639, the shogunate expelled the Portuguese and fully implemented its policy of national isolation. The only remaining European trading post was the Dutch trading house on Dejima in Nagasaki.From then on, Japan’s knowledge of the West was limited to what came through the Dutch, and the study of Dutch (Rangaku, or “Dutch learning”) flourished.

アダムズが亡くなってから約200年間、日本はオランダをヨーロッパ唯一の交易相手とする体制を築きました。1639年、幕府はポルトガル人を追放し、鎖国政策を本格化。ヨーロッパとの唯一の窓口として長崎・出島にオランダ商館が残されました。以降、日本の西洋に関する知識はオランダ経由のものに限られ、オランダ語(蘭学)が発展していきます。

Coast of Miura Peninsula

However, this situation drastically changed with the Phaeton Incident of 1808. One day, a ship suddenly appeared in Nagasaki Bay, flying the Dutch flag. The magistrate’s office responded as usual, sending interpreters and Dutch trading post staff to the ship, but events took an unexpected turn.

しかし、その状況が一変するきっかけとなったのが、1808年の「フェートン号事件」でした。その日、長崎湾に1隻の船が静かに姿を現し、オランダ国旗を掲げていました。奉行所は通常通り対応し、通訳や在留オランダ商館員を船に派遣しましたが、事態は予想外の展開を迎えます。Two Dutchmen who boarded the ship were suddenly taken hostage. The ship then lowered the Dutch flag and raised the British flag, revealing itself as an enemy vessel. This was nothing short of “piracy disguised as diplomacy.” From the ship, a threatening voice rang out: “Provide water, food, and firewood—or we will kill the hostages!”

船に乗り込んだオランダ人2名は、突如として乗組員に拘束され、人質にされました。さらに、船はオランダ国旗を降ろし、新たにイギリスの国旗を掲げたのです。これは、まさに「友好の仮面をかぶった海賊行為」でした。船上からは「水、食料、薪を供給せよ。さもなくば、人質を殺害する!」という脅迫の声が響き渡り、長崎の町に緊張が走りました。The magistrate’s office was outraged, declaring, “Foreigners residing in Japan are under our protection, just like our own people. We must do everything in our power to rescue the hostages!” However, Japan had no means to resist the ship’s overwhelming firepower and had no choice but to comply with its demands.

奉行所は激怒し、「たとえ外国人であろうと、日本に在留する者は我が国の人々同然。全力を尽くして人質を奪還せよ!」と命じたのです。しかし、圧倒的な武力を持つフェートン号に対抗する手段はなく、日本側はやむなく要求を受け入れるほかありませんでした。Thus, Japan provided water and firewood, and the hostages were released. However, the Phaeton continued to prowl Nagasaki Bay for three days, firing warning shots and disrupting the peace of the harbor. Finally, as if nothing had happened, the British ship left.

こうして、日本側は水や薪を供給し、人質は解放されました。しかし、フェートン号は威嚇の砲声を響かせながら長崎湾内を徘徊し、3日間にわたり港の平穏を揺るがし続けました。最終的に、何事もなかったかのように長崎湾を離れ、イギリス船は姿を消しました。The person who took the greatest responsibility for this incident was the Nagasaki magistrate at the time, Matsudaira Yasuyasu. Feeling deeply accountable for the disgrace brought upon Japan, he took his own life by committing seppuku.

この事件の責任を最も重く受け止めたのが、当時の長崎奉行・松平康英でした。彼は、日本の尊厳を傷つけたことへの責任を痛感し、自ら切腹してその命を絶ちました。Furthermore, during the incident, the interpreters on board made a shocking discovery. They learned that the once-dominant Netherlands had been occupied by France and Britain and was in decline. This alarming report heightened the shogunate’s sense of crisis, making it impossible for Japan to ignore the presence of English-speaking nations.

また、事件の際、船上で通訳を担当した通詞たちは驚くべき事実を耳にします。それは、かつての覇権国家であったオランダが、フランスやイギリスに占領され、衰退しているという情報でした。この衝撃的な報告は幕府の危機感を与え、日本は英語圏諸国の存在を無視できなくなります。 -

Japanese, the ‘mother sounds’ language, creates a world filled with compassion and sentiment.

- Hiragana Times

- Sep 20, 2024

[Kagawa Teruyuki’s Nihongo Do – October 2024 Issue]

Japanese, the ‘mother sounds’ language, creates a world filled with compassion and sentiment.

「母音言語・日本語」が創る思いやりと情感あふれる世界。Editor-in-Chief (EIC): The most widely used script in the world is the Latin alphabet, with English, German, and French using its 26 letters.

編集長: 世界で最も多く使用されている文字はラテンアルファベットで、英語、ドイツ語、フランス語はその26文字を使用しています。Kagawa: Hebrew has 22 letters. In contrast, Japanese has 50 sounds.

香川: ヘブライ語は22文字です。それに対して、日本語は50音。EIC: Japanese sentences are written using a mixture of kanji and kana, so it is considered a very complex language.

編集長: 日本語の文章は漢字かな混じりですから、非常に複雑な言葉だと捉えられています。Kagawa: Furthermore, a major difference between Japanese and other languages is that it is a “mother sounds” (vowels) language.

香川: もう一つ、日本語が他の言語と大きく異なるのは「母音言語」であることですね。EIC: That’s certainly true.

編集長: 確かにそうですね。Kagawa: In English, it’s common for words to end with consonants like “t” or “r,” but in Japanese, all words end with “vowels” (a, i, u, e, o), except for “n.”

香川: 英語には、tやrなど子音で終わる言葉も多くありますが、日本語はすべての言葉が、「ん」を除き、母音(あいうえお)で終わります。EIC: All 22 letters in Hebrew are consonants. We could say that the West is generally a “consonant culture.”

編集長: ヘブライ語の文字は全てが子音です。西洋はおおよそ「子音文化」と言えます。Kagawa: This isn’t limited to the West; nowadays, countries like Indonesia and the Philippines also use the Latin alphabet due to the influence of colonialism.

香川: 西洋にとどまらず、今ではインドネシアやフィリピンなども、植民地時代の影響でラテンアルファベットを使う国になっています。EIC: The Latin alphabet, or the “consonant culture sphere,” has spread worldwide.

編集長: ラテンアルファベット圏、つまり「子音文化圏」は世界中に広がりましたね。Kagawa: That might have some connection to the state of the world.

香川: それが世界の情勢と何らかの関係があるのかもしれません。EIC: Incidentally, in ancient Japanese kototama studies (the dynamics of the spirit becoming sound), in addition to “mother sounds” (vowels) and “children sounds” (consonants), there is also a sound called “father sounds.”

編集長: ちなみに、日本古代の言霊学[ことたまがく]には、母音(ぼおん)、子音(しおん)に加え、「父韻(ふいん)」という音も存在します。Kagawa: What kind of sounds are those?

香川: それらはどんな音ですか?EIC: “Father sounds” are like brief sparks and refer to sounds like t (chi), y (i), k (ki), m (mi), s (shi), r (ri), h (hi), and n (ni).

編集長: 父韻は一瞬の火花のような存在で、t(チ), y(イ), k(キ), m(ミ), s(シ), r(リ), h(ヒ),n(ニ)を指します。Kagawa: I see, so those “father sounds” combine with “mother sounds” (vowels) to create “children sounds” (consonants).

香川: なるほど、そうした父韻が母音に交わり子音が生まれるわけですね。EIC: Exactly as you said.

編集長: まさにおっしゃる通りです。Kagawa: In that case, what has spread worldwide might not be “consonant culture,” but rather “father sounds culture.”

香川: そうすると、世界に広まっているのは「子音文化」ではなく、むしろ「父韻文化」と言えるのかもしれません。EIC: Ah, that might be why there are so many fights.

編集長: ああ、だから戦いが多いのかもしれませんね。Kagawa: Perhaps the world should feel more of the “mother.”

香川: 世界はもっと「母」を感じてもいいですね。EIC: Consonants, when voiced continuously, return to vowels, and vowels resonate forever as vowels, no matter how long you voice them.

編集長: 「子音」は発声し続けると「母音」に還ります。そして、「母音」はどこまで発声しても永遠に「母音」のまま響き続けます。Kagawa: Indeed. Actually, Kabuki is an art form of “mother sounds” (vowels).

香川: そうですね。実は、歌舞伎は母音の芸能なのです。EIC: That’s fascinating. How are the vowels used?

編集長: それは興味深いです。どのように母音が使われているのですか?Kagawa: In Kabuki, vowels are called “umiji” (birth syllables).

香川:歌舞伎では母音のことを「うみじ(産字)」と呼びます。EIC: That’s the first time I’ve heard that.

編集長: 初めて耳にしました。Kagawa: For example, in the performance of “Yamato Takeru,” when calling “E-hime Korehe” (Princess Ehime, come here), the vowel “e” is extended and layered, as in “e-hime-e-e kore-e-e.” Without doing this, Kabuki cannot be performed.

香川:例えば、「ヤマトタケル」の演目で「兄橘姫(えひめ)これへ」と呼ぶ際、「えぇひぃぃめぇぇ こぉぉれぇぇえぇ」と「え」にさらに「え」を付けて母音を重ねます。これをしないと歌舞伎は成立しないのです。EIC: I see. That’s why Kabuki lines move people’s emotions, and perhaps that’s why its history has continued for so long, just like vowels.

編集長: なるほど。だから、歌舞伎のセリフには感情が揺さぶられるのですね。そして、その歴史も母音のように長く続いているのかもしれませんね。Kagawa: That may be true.

香川: そうかもしれません。EIC: That’s interesting. Related to this, some people say that the reason Japanese people struggle with learning English is because of “Katakana English.”

編集長: 面白いです。これに関連して、日本人が英語の習得を苦手とする原因は「カタカナ英語」にあると言う人がいます。Kagawa: I hear that a lot.

香川: よく耳にします。EIC: However, I believe it’s because Japanese, being a “mother sounds” (vowels) language, absorbs any foreign language and makes it its own.

編集長: しかしそれは、母音言語である日本語が、どんな外国語でも自分の言葉として取り込んでしまうことによるものだと思います。Kagawa: Any foreign language becomes Japanese. In the world of languages too, “the mother is strong,” and “mother sounds” (vowels) are strong. The fundamental reason Japanese people are said to struggle with English is that the influence of the “mother tongue” is too strong.

香川: どんな外国語も日本語になってしまう。言語の世界でも「母は強し」、母音は強しですね。日本人は英語が苦手だと言われる根本原因は、母語の力が強すぎるということですね。EIC: If Japanese people become aware of this, they might face foreign languages with more confidence. We should also cherish the Japanese language, which is our identity.

編集長: 日本人はこれを自覚すると、外国語に対してもっと自信を持って向き合えるかもしれません。そして自分たちのアイデンティティである日本語を大切にしていくべきです。Kagawa: Lately, it’s often said that this is the “age of women.” This doesn’t refer to gender but rather suggests that by resonating the “mother sounds” (vowels)—the sounds of sentiment—we might cultivate a kinder, more compassionate world.

香川: 最近はよく「女性の時代」と言われます。これは性別ということでなく、情念の音である母音を響かせることを指していると考えれば、そうあることで優しく思いやりある世界が拡がっていくことでしょう。EIC: And may that compassionate world echo eternally, like the “mother sounds.”

編集長: そして、その思いやりある世界が「母音」のように永遠に響き続けるといいですね。

This article is from the October 2024 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2024年10月号より掲載しています。

-

[Cover Story – September 2024 Issue]

This month’s feature is on the Japanese language and Kabuki. The cover features Kabuki actor Ichikawa Chusha (also known as actor Teruyuki Kagawa).

今月号の特集は、日本語と歌舞伎。表紙は歌舞伎俳優の市川中車さん(俳優の香川照之さん)です。

Kabuki, a popular culture born from the common people at the beginning of the Edo period, transformed from a common entertainment into a high-class traditional art during Japan’s rapid modernization under the influence of the Meiji Restoration. With the support of the upper class and intellectuals, Kabuki was redefined as an elegant culture.

江戸時代の初めに庶民から生まれた大衆文化である歌舞伎は、明治維新の影響で日本が急速に近代化を進める中、庶民の娯楽から格式の高い伝統芸能へと変貌しました。上流階級や知識人層の支持を得ることで、歌舞伎は雅な文化として再定義されたのです。

“The rebellious spirit of Omodakaya did not accept this. My father, the third-generation Ichikawa Ennosuke, was concerned about the state of the Kabuki world, where only traditional performances were staged. He created a new performance called ‘Yamato Takeru.'”

「反骨の精神を持つ澤瀉屋はそれをよしとしませんでした。私の父である三代目市川猿之助は、伝統に捉われた演目ばかりが演じられる歌舞伎界の現状を危惧し、新たに『ヤマトタケル』という演目を作り上げました」

The newly created Super Kabuki became a stage art that skillfully incorporated modern elements while retaining its classical charm, attracting many audiences. Merely preserving tradition is just maintaining the status quo; evolution is necessary to create new forms. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the spirit of Omodakaya, often considered unconventional, has supported the transformation of Kabuki.

こうして生み出されたスーパー歌舞伎は、古典的な魅力を保ちながらも現代的な要素を巧みに取り入れた舞台芸術となり、多くの観客を惹きつけました。伝統を守るだけでは現状維持に過ぎず、新たな形を創り出すためには進化が必要です。異端とも評される澤瀉屋のスピリットが、その後の歌舞伎の変革を支えてきたと言っても過言ではないでしょう。

We have planned a special series where Mr. Chusha will talk about Kabuki and the Japanese language in this month’s issue and the next October issue. Let’s learn from Mr. Chusha, who expresses that he feels “constantly connected to the heavens through words,” about the spirit residing in the Japanese language.

今月号と次号10月号で、中車さんに、歌舞伎と日本語について語っていただく集中連載を企画しました。「言葉を介して常に天とつながっているような感覚がある」と日本語を表現する中車さんに、日本語に宿る魂について教えていただきましょう。

Text: IKEDA Miki

文: 池田 美樹 -

Japan as Seen by Foreigners in History – 歴史上の外国人が見た日本

[Echoes of Japan – April 2024 Issue]

Among the historical figures widely known in Japan, many foreigners visited Japan and left comments or episodes about the country.

日本で広く知られる歴史上の人物の中には、来日して日本についてのコメントやエピソードを残した外国人もたくさんいます。

At the end of the 16th century, when Japan was in the Sengoku period, the world was said to be in the Age of Exploration.日本が戦国時代であった16世紀末、世界は大航海時代と言われる時代でした。

Christian missionary Francis XAVIER comes to Japan from Portugal for missionary work.

ポルトガルからキリスト教の宣教師、フランシスコ・ザビエルが布教のために来日します。

Xavier and his missionary group stated in letters that the Japanese people possess splendid culture and high morals, surpassing any other non-Christians, valuing honor more than money within their hierarchical society.

ザビエルら宣教師一行は、日本人は素晴らしい文化と高いモラルを持ち、どの異教徒よりも優秀で、階級社会の中で金銭よりも名誉を重んじて生きていると書簡で述べています。

“History of Japan” written by the missionary Luis FROIS has become a valuable source for understanding medieval history.

宣教師のルイス・フロイスが書いた「日本史」は、中世史を知る貴重な資料となっています。

It is said that this document strongly reflects the individual’s position and emotions, as it highly praises ODA Nobunaga, the ruler of this era, while harshly criticizing TOYOTOMI Hideyoshi, who succeeded him in unifying the country.

この時代の覇者である織田信長を非常に高く評価する一方で、その次に天下統一を成し遂げた豊臣秀吉を酷評するなど、個人の立場や感情が強く反映されている資料とも言われています。

Nobunaga, who adopted Western civilization, was tolerant of Christian missionary work. Hideyoshi inherited Nobunaga’s policies but upon learning that the Portuguese were buying and enslaving Japanese people, he banned missionary work and expelled the missionaries.

西洋文明を取り入れた信長はキリスト教の布教に寛大でした。秀吉は信長の政策を引き継ぎましたが、ポルトガル人が日本人を売買して奴隷にしていると知り、布教を禁止して宣教師を追放しました。

From the beginning of the Edo period when the country closed its doors, through the opening of Japan in the late Edo period, to the early Meiji period (17th to 19th centuries), many records exist where foreign visitors wrote about their impressions of Japan.

鎖国が始まった江戸時代初期から、幕末の開国以降、大勢の外国人がやってきた明治時代初頭(17~19世紀)にかけて、訪日外国人が日本の印象を記した記録がたくさんあります。

The German physician Philipp SIEBOLD arrived in Japan as a Dutchman and was impressed by the unmanned vending stalls, where priced items were displayed, in Edo (modern-day Tokyo).

オランダ人として来日したドイツ人医師のフィリップ・シーボルトは、江戸(現在の東京)で値段がつけられた商品が並ぶ箱、つまり無人販売所を見て感動します。

Heinrich SCHLIEMANN, a German archaeologist, noted that the boatman returned him extra money when he rode a ferry in Japan.

ドイツの考古学学者、ハイリッヒ・シュリーマンは、日本で渡し船に乗った時に、船頭が余分なお金を返してくれたことを記しています。

Also, many foreigners who have visited Japan have left numerous comments about the country.

この他にも、日本を訪れた外国人が日本について多くのコメントを残しています。

These comments cover a wide range of topics, including the beauty of nature and the richness of the four seasons, as well as Japan’s expertise in learning from foreign cultures, such as which flowers are planted in each house and the literacy of the common people.

自然の美しさや四季の豊かさはもちろんのこと、どの家にどのような花が植えられているか、日本人は外国から学ぶのが得意であること、庶民も読み書きできるなど、内容は多岐にわたります。

It can be said that these cultural aspects praised by foreigners have been inherited in present-day Japan.

外国人が称賛したこれらの文化は、現在の日本にも引き継がれていると言えるでしょう。

-

What Are the Genetic Roots of the Japanese People? – 日本人の遺伝子ルーツは?

[Echoes of Japan – March 2024 Issue]

Japan is experiencing issues such as depopulation in rural areas, labor shortages, and concerns about pension payouts.

日本では地方における過疎化や人手不足、 年金給付への不安などの問題が起きています。

To solve these issues, the government is actively promoting policies to countermeasure declining birth rates and support child-rearing, but the situation has not significantly improved.

それらを解消するために、政府は少子化対策や子育て支援の政策を進めていますが、改善されていないのが現状です。

Without a sufficient workforce, economic growth is not feasible. In this context, attention is turning to immigrants from overseas.

働き手がいなければ経済成長は望めません。 そんな中で注目されているのが海外からの移住者です。

Japan has largely refrained from accepting refugees. This is partly due to Japan being a nearly homogenous island nation with a single ethnicity and language, and a strong consciousness of preserving its unique culture and morals.

日本は難民をほとんど受け入れてきませんでした。 それは、日本がほぼ単一民族、単一言語の島国であること、 独く自の文化やモラらルるを守りたいという意識が強いこともあります。

Japan’s history began in the Paleolithic era, and around 12,000 years ago, it transitioned to the Jomon period, characterized by a lifestyle centered around hunting. It is said to have been a prosperous era of over 10,000 years in peace.

日本の歴史は旧石器時代から始まり、 約 1 万2千年前には狩猟生活を主とする縄文時代へと移りました。 1万年以上も 平和が続く豊 かな時代だったと言われています。

Later, around the 5th century BCE, ethnic groups from the continent migrated to Japan. This ushered in a new era known as the Yayoi period (3rd century BCE to 3rd century CE). Rice cultivation spread and iron tools emerged in the later stages.

その後、紀元前5 世紀頃から大陸から移民族がやっ てきます。日本は新たな時代、弥生時代(紀元前3 世紀~ 3 世紀)へ移りました。稲作が広がり、後期 には鉄器が出現します。

Until now, it has been believed that the roots of the Japanese people are Jomon people, the indigenous inhabitants of Japan, Yayoi people, descendants of immigrants who arrived from the continent, and are a mix of both people with Japanese culture being shaped by them.

これまで日本人のルーツは、日本に先住していた縄 文人と、大陸からやってきた渡来人の混合子孫であ る弥生人であり、彼らによって日本文化がつくられ たとされてきました。

However, the latest research on DNA analysis of human bones excavated from a site dating from the Kofun period (3-7th century), which began after the Yayoi period, has revealed that about 60% of their genetic genome is mainly East Asian in South descent and does not match either the Jomon or the migratory people.

しかし、弥生時代の次に始まる古墳時代(3 ~ 7 世紀)の遺跡から発掘された人骨を最新の研究で DNA 解析した結果、その遺伝子ゲノムの約60%は 主に東アジアの南方系であり、縄文人とも渡来人の ものとも一致しないことが判明しました。

It is becoming apparent that the genetic roots of modernday Japanese people extend across the entire East Asian region.

現代日本人の遺伝子のルーツが、東アジア全域に広 がっていることがわかりつつあります。

It can be inferred that during the Kofun period, a significant influx of people with East Asian in South ancestry migrated to Japan.

古墳時代には東アジアの南方系に祖先を持つ人々が 大量に移住してきたことが推察できます。

From the later part of the Yayoi period to the Kofun period, during which massive tomb mounds suddenly appeared, there is, unfortunately, no material found in Japan or China about those 150 years.

弥生時代の後期から、巨大な墳墓が突然登場する 150 年間の古墳時代についての資料は、残念なこと に日本でも中国でも発見されていません。

It remains unclear what events transpired during this period, leading to a significant influx of migrants. It’s possible that a migration era, similar to the modern-day USA, occurred.

この間にどのような出来事が起きて活発な移住者流 入があったのかはわかっていませんが、近代のアメ リカのような大移住者時代が存在したのかもしれま せん。

In any case, Japan’s highly distinctive unique culture can be said to have emerged through a period when the indigenous people of ancient Japan and those who migrated from the continent mixed.

いずれにしても独自性が高い日本の文化は、先住日 本人と大陸から移り住んだ人々が混在した時代を経 てつくられたと言えるでしょう。

Ancient Japan had no borders.

古代の日本には国境がありませんでした。

There is a growing sentiment in many countries that the Japanese mentality and culture of caring for others should become a global norm.

他人を思いやる日本人の精神性や文化は世界の規範 になるべきだとの声が、多くの国々で高まってい ます。

Perhaps now is the time for Japan to warmly embrace the migrants, refugees, and foreign workers who choose Japan to solve their problems, and together spread a culture of compassion throughout the world.

日本は今、日本を選ぶ移住者、難民、外国人労働者 を温かく受け入れて諸問題の解決を図り、共に思い やり文化を世界に広げていくときかもしれません。

Information From Hiragana Times

-

February 2026 Issue

January 21, 2026

February 2026 Issue

January 21, 2026 -

January 2026 Issue – Available as a Back Issue

January 15, 2026

January 2026 Issue – Available as a Back Issue

January 15, 2026 -

December 2025 Issue —Available as a Back Issue

November 20, 2025

December 2025 Issue —Available as a Back Issue

November 20, 2025