-

[JAPAN MAZE | 迷宮ニホン – February 2026 Issue]

You may understand the words, but still get lost in communication. This corner takes you on a fun journey through the maze of Japanese language and culture with four-panel manga. Unlocking the punchline is the key – it reveals the essence of Japanese expression and leads you to the exit, with a smile and a fresh insight.

言葉の意味はわかるのに、なぜか通じない――。日本語と日本文化の迷宮を、4コマ漫画で楽しく探検するコーナーです。 “オチ”を読み解けば、日本語の本質が見えてくる。迷宮の出口には、気づきと笑いが待っています。

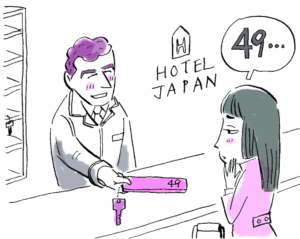

チェックイン | Check in

Scene 1

スタッフ:ごゆっくりどうぞ。

Staff : Take your time.日本人客:でも、番号がシキュウ。

Japanese guest : But, the number reads shikyuu (urgent).Scene 2

スタッフ:お部屋の番号が気になりますか。

Staff: Are you concerned about room numbers?日本人客:縁起の悪い数字ですからね。

Japanese guest : I am, because it’s an unlucky number.Scene 3

スタッフ:では、53号室が空いてますが …… 。

Staff : Well then, room 53 is available.日本人客:今度はゴミ部屋?

Japanese guest : This time it’s the garbage room is it?Scene 4

スタッフ:すみません。39号室はいかがですか。

Staff : I’m sorry. How about room 39?日本人客:いいですね。サンキュウ。

Japanese guest : Good. Thank you.

Maze Navigation / 迷宮ナビ

Let’s break down each scene | それぞれのシーンを理解しよう。Scene 1

At hotel check-in, the staff assigns Room 49. In Japanese, 4 is read “shi” and 9 is read “ku,” and together they form shikyuu, meaning “urgent.”

ホテルのチェックイン。スタッフは49号室を案内します。日本では、4は「し」、9は「きゅう」と読み、合わせると「至急」という意味になります。そのため、「しきゅう」と言われた案内と、部屋番号の意味が矛盾します。

■ 案内する [to guide / to assign]

■ 至急 [urgent]

■ 意味 [meaning]

■ 矛盾する [to contradict]Scene 2

The receptionist thinks the guest is simply worried about the room number. In Japan, both 4 (shi) and 9 (ku/kyuu) are seen as unlucky: shi sounds like “death,” and ku sounds like “suffering.” This superstition makes the guest uneasy.

スタッフは、お客が番号を気にしているのだと思っています。日本では、4(し)は「死」、9(く/きゅう)は「苦」と連想させる不吉な数字とされています。そのため、客はどうしても気になってしまいます。

■ 番号 [number]

■ 気にする [to be concerned about]

■ 不吉 [unlucky / ominous]

■ 死 [death]

■ 苦 [suffering / hardship]Scene 3

Now the guest is being shown to Room 53. But 5 can be read go and 3 can be read mi, which together form gomi (“garbage”). So the guest can’t help thinking, “A garbage room?”

今度は53号室を案内します。しかし、5は「ご」、3は「み」とも読み、続けると「ゴミ」になります。そのため客は「ゴミ部屋?」と連想してしまいます。

■ 続ける [to put together / to combine]

■ ごみ [garbage / trash]

■ 連想する [to associate with / to be reminded of]Scene 4

Finally, they suggest Room 39. The number 39 can be read san-kyuu, which sounds very close to “thank you” in English. This kind of wordplay is something many Japanese people enjoy.

最後は39号室を提案しました。39は「サンキュー」と読めるため、英語の “thank you” によく似た音になります。こうした語呂合わせは、日本人にとても親しまれています。

■ 提案する [to suggest]

■ 語呂合わせ [wordplay / pun]

■ 親しまれている [be liked / be familiar to]

Maze Exit / 迷宮出口

What did the punchline reveal? / 今回のオチでわかったことCultural Insight / 新しい発想・文化知識

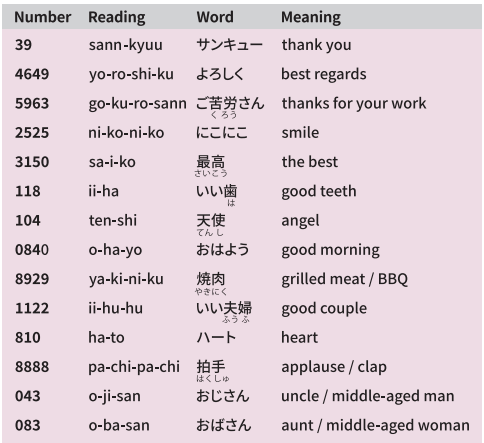

Goro-Awase, Hidden Codes, and Wordplay in Japanese Numbers

数字が語る日本語の世界Japanese numbers carry more than numerical value—they echo sounds, meanings, and even hidden messages. From playful goro-awase puns to coded expressions used online, numbers in Japanese culture often “speak” in creative and surprising ways. Once you begin to recognize these patterns, simple digits start to reveal humor, and personality.

日本語の数字は、単なる数ではなく、音や意味、リズムをもって“語る”存在です。語呂合わせや隠語、ネット表現など、数字は日本語文化の中で多様な役割を担っています。仕組みを知ると、数字の裏に潜むユーモアや感性が見えてきます。

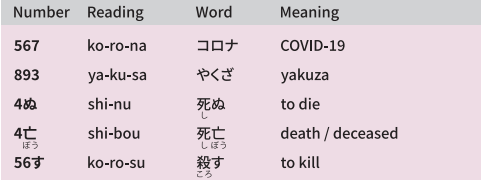

Standard & Useful Goro-awase

一般の語呂合わせ

Hidden slang, BAN-avoidance, and other coded number expressions

隠語・BAN回避などの数字表現On platforms where certain words (death, violence, illness, etc.) may be restricted, Japanese speakers often use numbers to express those concepts indirectly. Some of these codes also come from long-standing slang or subcultural usage.

SNSや動画サイトでは、死亡・暴力・病名などがNGワードになることがあり、数字で言い換える文化があります。また、古くから使われる隠語の数字も存在します。

This article is from the February 2026 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2026年2月号より掲載しています。

-

[JAPAN MAZE | 迷宮ニホン – January 2026 Issue]

You may understand the words, but still get lost in communication. This corner takes you on a fun journey through the maze of Japanese language and culture with four-panel manga. Unlocking the punchline is the key – it reveals the essence of Japanese expression and leads you to the exit, with a smile and a fresh insight.

言葉の意味はわかるのに、なぜか通じない――。日本語と日本文化の迷宮を、4コマ漫画で楽しく探検するコーナーです。 “オチ”を読み解けば、日本語の本質が見えてくる。迷宮の出口には、気づきと笑いが待っています。

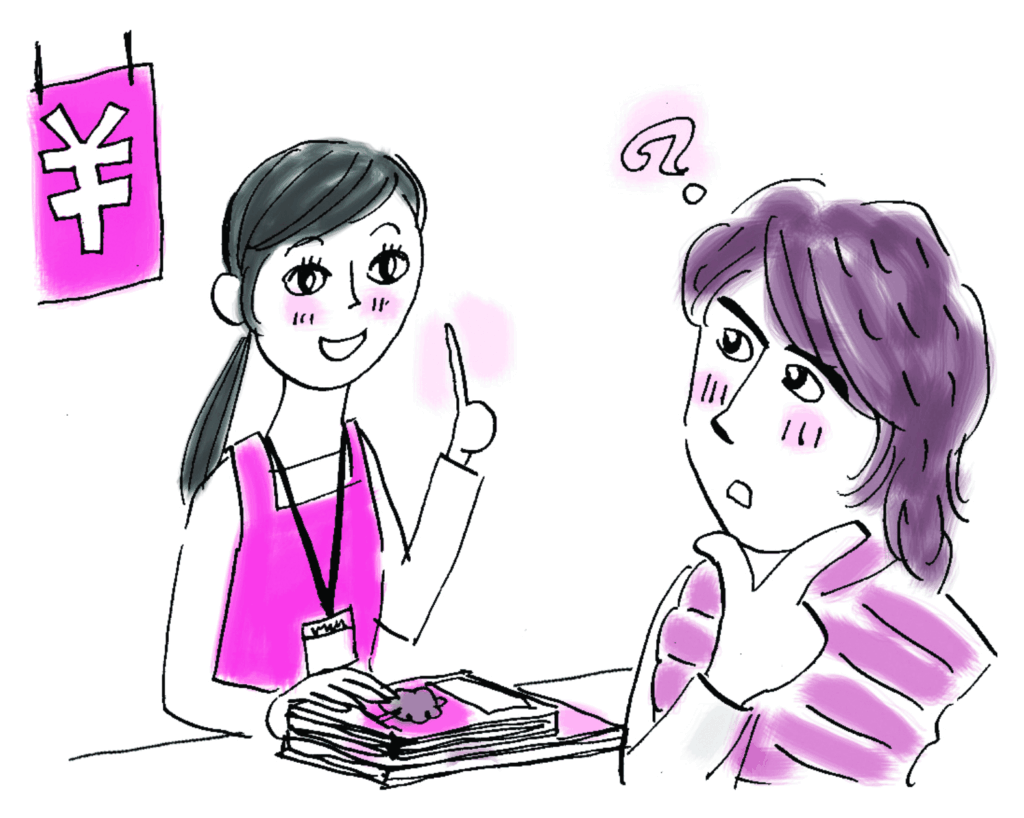

もういっぱい | Another Drink

Scene 1

ホストマザー:お茶はいかがですか。

Host Mother: How about a cup of tea?

留学生:ありがとう。

Foreign Student: Thank you.

Scene 2

留学生:とてもおいしい。

Foreign Student: It’s really good.ホストマザー:そう、それではもう一杯いかがですか。

Host Mother: Well then, how about another cup?Scene 3

留学生:すみません。もういっぱい。

Foreign Student: Thank you, I have had enough.ホストマザー:あなた、本当にお茶が好きなんですね。

Host Mother: You really like tea.

さあ、さあ。

Please please.Scene 4

留学生:もういっぱい。たくさんです

Foreign Student: I have had enough, no more thanks.ホストマザー:そう、どうぞ、どうぞ。たくさん飲んで!

Host Mother: Good, please, please. Drink a lot!

Maze Navigation / 迷宮ナビ

Let’s break down each scene | それぞれのシーンを理解しよう。Scene 1

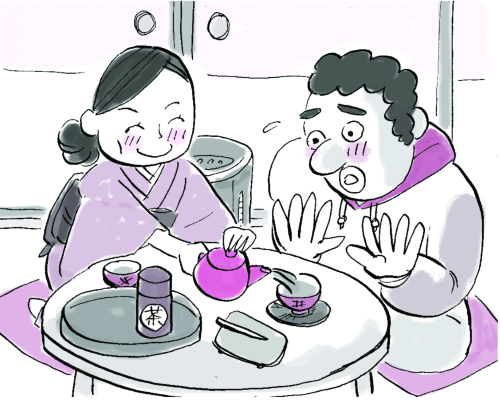

When visiting a Japanese home, it is common to be welcomed with a warm cup of tea. In this scene, the host mother offers tea to a student who has just arrived in Japan. Serving tea is a Japanese custom that expresses “welcome,” and the student gladly responds.

日本の家庭を訪問すると、温かいお茶でもてなされることがよくあります。このシーンでは、訪日したばかりの留学生に、ホストマザーがお茶を勧めています。お茶は「ようこそ」の気持ちを伝える日本の習慣で、留学生も喜んで応じています。

■ 家庭 [home]

■ もてなす [to welcome / to treat]

■ 勧める [to offer / to recommend]

■ 習慣 [custom]Scene 2

In many Japanese homes, a hot-water pot is kept so that tea can be prepared anytime. The host mother pours hot water into a teapot and carefully serves the tea into a cup. The student relaxes and smiles, saying it tastes good.

日本の家庭では、温かいお茶をすぐ入れられるよう、保温ポットを置いていることがよくあります。ホストマザーは急須にお湯を注ぎ、丁寧に湯呑みにお茶をついでいます。留学生はリラックスし、おいしいと、笑顔を見せています。

■ 保温 [keep warm]

■ 急須 [teapot]

■ お湯 [hot water]

■ 注ぐ [to pour]

■ 丁寧に [carefully / politely]Scene 3

The student thinks he is saying “mō ippai,” meaning “I’ve had enough,” but the host mother hears it as “mō ippai,” meaning “one more cup.” This misunderstanding leads her to assume he reallyt loves tea, and she continues to offer him more.

留学生は「もういっぱい、イコール、もう十分です、と断っているつもりですが、ホストマザーはそれを、もう一杯、イコール、おかわり、と受け取りました。行き違いが生まれ、お茶好きだと思い込んだホストマザーは、さらに勧めています。

■ 断る[to refuse]

■ 受け取る[to take, to interpret as]

■ 行き違い[misunderstanding]

■ 思い込む[to assume]Scene 4

Finally, the student says, “Mō ippai, takusan desu,” meaning he’s had more than enough. However, the host mother hears it as “One more cup, a lot please,” and continues pouring tea for him.

とうとう、留学生は「もういっぱい、たくさんです」と断っていますが、ホストマザーはそれを「もう一杯、たくさん欲しい」と受け取り、さらにお茶を注ぎます。

■ もう一杯 [one more cup]

■ いっぱい [enough / full]

■ たくさん [a lot]

■ さらに [further / additionally]

Maze Exit / 迷宮出口

What did the punchline reveal? / 今回のオチでわかったことCultural Insight / 新しい発想・文化知識

Japanese has an exceptionally large number of homophones—words that sound the same but have different meanings. This may seem difficult at first, but English has similar examples such as “knight” and “night,” or “pair” and “pear.” Even when words sound identical, their meanings become clear from context.

日本語には、音が同じで意味が異なる言葉(同音異義語)が非常に多く存在します。最初は難しく感じるかもしれませんが、英語にも “knight / night” や “pair / pear” のような例があります。音が同じでも、文脈によって意味は自然に理解されます。

Homophones in Japanese form a world where depth and playfulness coexist. They sound the same to the ear, yet look and feel different to the eye—this duality is part of the charm of the Japanese language.

同音異義語は、日本語の奥深さと遊び心が混ざり合った世界。耳では同じ、目では違う、その二重性こそが、日本語の魅力です。

This article is from the January 2026 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2026年1月号より掲載しています。

-

[JAPAN MAZE | 迷宮ニホン – December 2025 Issue]

You may understand the words, but still get lost in communication. This corner takes you on a fun journey through the maze of Japanese language and culture with four-panel manga. Unlocking the punchline is the key – it reveals the essence of Japanese expression and leads you to the exit, with a smile and a fresh insight.

言葉の意味はわかるのに、なぜか通じない――。日本語と日本文化の迷宮を、4コマ漫画で楽しく探検するコーナーです。 “オチ”を読み解けば、日本語の本質が見えてくる。迷宮の出口には、気づきと笑いが待っています。

レストルーム | Restroom

Scene 1

ゆみ:どうなさいましたか。

Yumi: What’s the matter?

Scene 2

ジミー:レストルームはどこですか。

Jimmy: Where’s the restroom?ゆみ:大丈夫ですか。

Yumi: Are you ok?Scene 3

ジミー:がまんできます。

Jimmy: I can’t hold on.ゆみ:でも、お体が震えていらっしゃいます。

Yumi: But… you are shaking.Scene 4

ジミー:どこか教えてください、早く!

Jimmy: Tell me where it is, hurry!ゆみ:あ、保健室へご案内いたします。

Yumi: I’ll take you there. Let the nurse take a look at you.

Maze Navigation / 迷宮ナビ

Let’s break down each scene | それぞれのシーンを理解しよう。Scene 1 — “Something’s Wrong!”|「なにか変!?」

At the information counter, Jimmy, a foreign man, approaches Yumi. He seems restless and troubled.

ビルの案内所で、外国人のジミーがゆみに話しかけます。どこか落ち着かず、困っている様子です。■ 案内所[information counter]

■ 外国人[foreigner]

■ 様子[appearance / situation]

■ 困る[to be troubled]

■ 緊張[nervousness]Scene 2 — “The Restroom Riddle”|「レストルームのなぞ」

Jimmy asks Yumi where the restroom is. But Yumi thinks he’s looking for a place to rest!

ジミーは「レストルームはどこですか?」と尋ねますが、

ゆみは「休む部屋」を探していると勘違いします。■ 休む[to rest]

■ 部屋[room]

■ 探す[to look for]

■ 尋ねる[to ask / to inquire]

■ 勘違い[misunderstanding]

■ 通じない[not understood / miscommunication]Scene 3 — “Can’t Hold It!!”|「もう限界!」

Jimmy is desperate to go to the toilet,

but Yumi doesn’t realize his urgency and only shows concern.ジミーは今すぐトイレに行きたいのに、

ゆみは心配するばかりで状況を理解していません。■ 今すぐ[right away / immediately]

■ 震える[to tremble / to shake]

■ 我慢できない[can’t hold it / can’t endure]

■ 状況[situation / condition]

■ 心配[worry / concern]Scene 4 — “Hospital Instead!?”|「トイレじゃなくて保健室!?」

Jimmy gets impatient,

while Yumi, misunderstanding his condition,

decides to take him to the infirmary.焦るジミーを見て、ゆみは「体調不良」と思い込み、

保健室へ連れて行こうとします。■ 案内する[to guide / to escort]

■ 看護師[nurse]

■ 焦る[to panic / to be flustered]

■ 診る[to examine / to check (a patient)]

■ 体調不良[feeling unwell]

■ 思い込む[to assume / to believe mistakenly]

Maze Exit / 迷宮出口

What did the punchline reveal? / 今回のオチでわかったこと

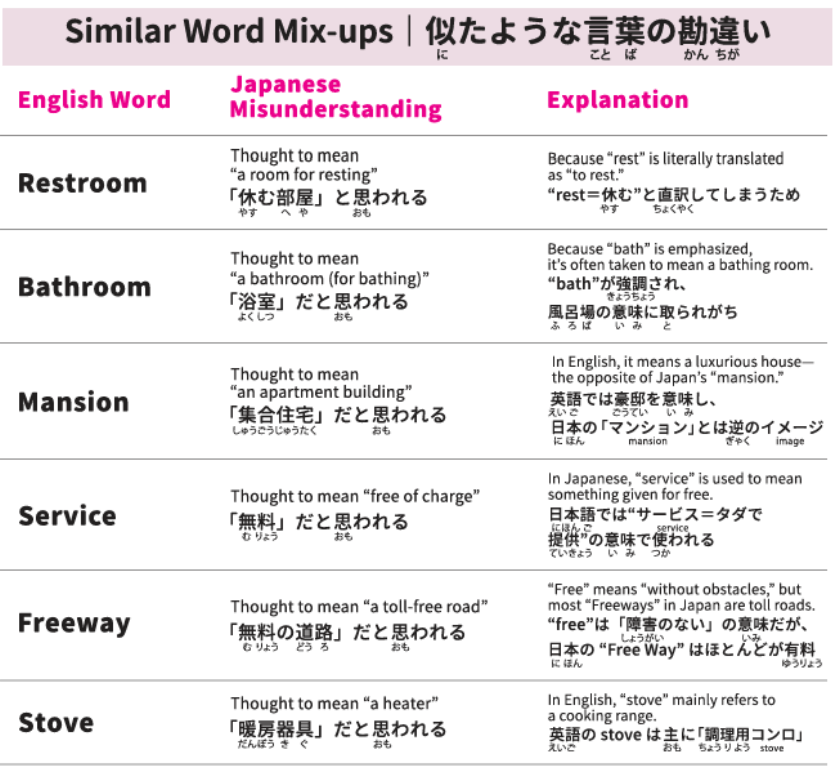

Cultural Insight / 新しい発想・文化知識In Japan, the word “toilet” is the most common expression, and few people know that “restroom” means the same thing.

Another common term is “otearai”, which literally means “a place to wash your hands,” but it is used in the same way as “bathroom” in English.日本では「トイレ」という言葉が一般的で、「restroom=トイレ」と知る人は少ないのです。

もう一つの言い方に「お手洗い」があり、直訳すると「手を洗う場所」ですが、英語の “bathroom” のようにトイレを意味します。Most Western-style toilets in Japan come with a variety of advanced features.

You can adjust the seat temperature, and many include a warm-water washing function.

In addition, there are options for water pressure control, warm-air drying, deodorizing, and even sound-masking systems that let users feel more comfortable.日本の洋式トイレのほとんどには、さまざまな機能がついています。

便座の温度を調整できるほか、お湯でお尻を洗う「温水洗浄」機能もあります。

そのほかにも、水量の調整、温風での乾燥、脱臭、さらに音を気にしないで済む「消音装置」など、多様な工夫がされています。There is also a saying in Japan that “a toilet reflects the heart of the household.”

A clean and well-kept toilet is seen as a symbol of hospitality.

In both homes and businesses, keeping the toilet clean is considered important, and there is even a belief that cleaning the toilet brings good luck.また、日本では「トイレはその家の“心”を映す」と言われます。

清潔で整えられたトイレは、おもてなしの象徴です。

家庭や店舗ではトイレ掃除を大切にする文化が根づいており、

「トイレをきれいにすると運が良くなる」という言い伝えもあります。

This article is from the December 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年12月号より掲載しています。

-

[JAPAN MAZE | 迷宮ニホン – November 2025 Issue]

You may understand the words, but still get lost in communication. This corner takes you on a fun journey through the maze of Japanese language and culture with four-panel manga. Unlocking the punchline is the key — it reveals the essence of Japanese expression and leads you to the exit, with a smile and a fresh insight.

言葉の意味はわかるのに、なぜか通じない――。日本語と日本文化の迷宮を、4コマ漫画で楽しく探検するコーナーです。“オチ”を読み解けば、日本語の本質が見えてくる。迷宮の出口には、気づきと笑いが待っています。

手を打て | Clap your hands te wo ute

Scene 1

社員: 課長! 安倍さんの電車が遅れています。

kachou! abe san no densha ga okurete imasu

Staff: Section chief! Mr. Abe’s train has been delayed.

課長: 何ですって! もうすぐ大事なプレゼンが始まるのに。

nandesutte! mou sugu daijina purezen ga hajimaru noni.

Chief: What! We are due to start giving an important presentation soon.

Scene 2

社員: どうしましょうか?

dou shimashou ka?Staff: What shall I do?

課長: すぐ手を打ちなさい。

sugu te wo uchinasai

Chief: Act quickly to resolve the problem.

Scene 3

社員: はい、神社はこちらの方向でしたね?

hai, jinja wa kochira no houkou deshita ne?

Staff: Ok. The shrine is this way, isn’t it?

課長: 何しているの?

nani shite iru no?

Chief: What are you doing?

Scene 4

社員: 神様に解決をお願いしました。

kamisama ni kaiketsu wo onegai shimashita

Staff: I prayed to the gods to solve our problem.

課長: お手上げだね。

oteage da ne

Chief: I throw up my hands.

Maze Navigation / 迷宮ナビ

Let’s break down each scene | それぞれのシーンを理解しよう。Scene 1

In Japan, staff address their superiors by their job title, as in “kachou (section chief),” instead of by name. The word “presentation” is now used in Japanese, but it is generally shortened to “purezen.”

日本では、社員は上司を名前で呼ばずに「課長」のように役職で呼ぶのが一般的です。「プレゼンテーション」は近年日本語としても使われますが、一般的に「プレゼン」と短く言います。

Keywords

■社員 (shain): staff ■上司 (joushi): superiors ■課長 (kachou): section chief ■役職 (yakushoku): job title ■一般的 (ippanteki): common ■近年 (kinen): recent years

Scene 2

The phrase “te wo utsu” means “to plan” and “take action to solve an issue.”

「手を打つ」は解決のための策を立てるという慣用句です。

Keywords

■手を打つ (te wo utsu): to plan / take action to solve an issue ■解決 (kaiketsu): solution ■策 (saku): measures ■立てる (tateru): stand up ■慣用句 (kanyouku): Idiom

Scene 3

When Japanese pray for something, they go to a shrine. It is customary to clap one’s hands together before the altar. He has misunderstood his boss and thinks that he has been asked to pray.

日本人は何かお願いごとをするときに神社に行きます。拝殿の前では手を叩くのが慣習です。社員はそうしろと言われたと勘違いしたのです。

Keywords

■神社 (jinja): shrine ■拝殿 (haiden): worship hall ■手をたたく (te wo tataku): clap one’s hands ■慣習 (kanshuu): custom ■勘違い (kanchigai): misunderstanding

Scene 4

The phrase “o te age” means “I’ve given up hope.” This literally means “raising hands,” a phrase related to “hands.”

「お手上げ」は「どうしようもない」というフレーズです。これは「手を上げる」という意味で、手に関する慣用句の一つです。

Keywords

■お手上げ (oteage): giving up ■どうしようもない (doushiyoumonai): no way ■手を上げる (te wo ageru): give up

Maze Exit / 迷宮出口

What did the punchline reveal? / 今回のオチでわかったこと

Cultural Insight / 新しい発想・文化知識

The Culture of “Hand” in the Japanese Language日本語に息づく「手」の文化

There is an astonishing number of expressions in Japanese that involve the word “te” (hand). Since ancient times, the Japanese have regarded the hand as an organ that connects to the heart. Craftspeople put their souls into their handiwork, and in traditional arts such as tea ceremony and calligraphy, the way one moves the hands is said to reflect one’s inner self. In other words, the hand is an extension of the heart – a visible expression of one’s character. The abundance of hand-related expressions mirrors a cultural spirit in which feelings are conveyed not through words, but through action. Here are some common Japanese expressions that include “hand.”

日本語には「手」に関わる表現が驚くほど多くあります。古くから日本人にとって「手」は、“心”とつながる器官でした。職人が手仕事に魂を込め、茶道や書道などの芸道では「手つき」「手の運び」がその人の内面を映し出すとされます。つまり、手とは心の延長であり、目に見える人格のあらわれでもあったのです。「手」にまつわる言葉の多さは、行動を通して心を表す日本人の精神文化を映す鏡でもあるのです。そんな「手」に関係する表現を、いくつかまとめてみました。

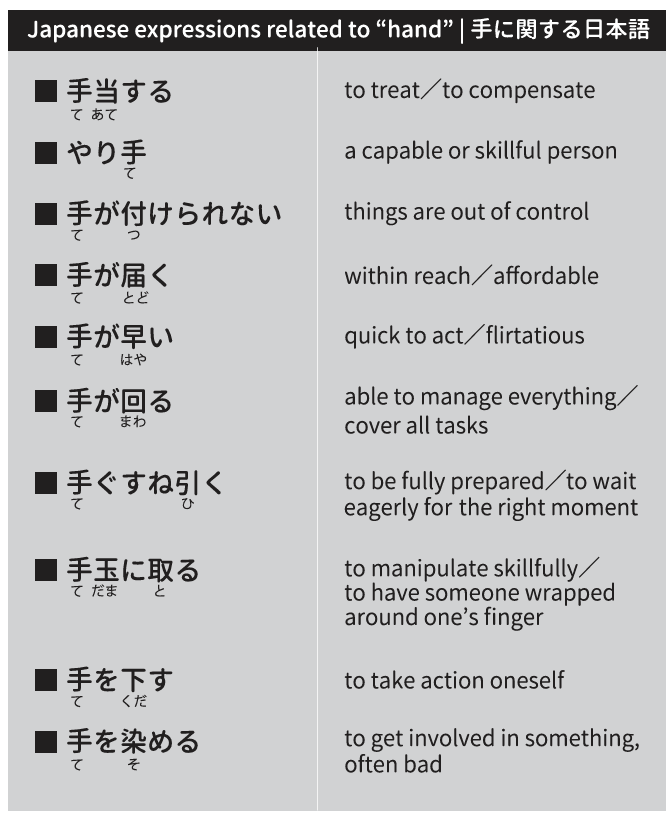

Japanese expressions related to “hand” | 手に関する日本語

This article is from the November 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年11月号より掲載しています。

-

[JAPAN MAZE | 迷宮ニホン – October 2025 Issue]

You may understand the words, but still get lost in communication. This corner takes you on a fun journey through the maze of Japanese language and culture with four-panel manga. Unlocking the punchline is the key — it reveals the essence of Japanese expression and leads you to the exit, with a smile and a fresh insight.

言葉の意味はわかるのに、なぜか通じない――。日本語と日本文化の迷宮を、4コマ漫画で楽しく探検するコーナーです。“オチ”を読み解けば、日本語の本質が見えてくる。迷宮の出口には、気づきと笑いが待っています。

誕生日の贈り物 | Birthday Present

Scene 1 ジョン: これ、誕生日の贈り物です。

ジョン: これ、誕生日の贈り物です。John: This is a birthday present.

ユイ: バースデープレゼント? サンキュウ!

Yui: A birthday present? Thank you!

Scene 2

ジョン: 首飾りです。

ジョン: 首飾りです。

John: It’s a necklace.

ユイ: ネックレスのことね?

Yui: You mean a necklace?

Scene 3

ジョン: 食堂へ行こう。ブドウ酒で乾杯しよう。

John: Let’s go to a restaurant and make a toast with wine.

ユイ: レストランで、ワインで乾杯ということね?

Yui: You mean make a toast with wine in a restaurant?

Scene 4

ジョン: ユイ、どうしていちいち英語で確認するの?

ジョン: ユイ、どうしていちいち英語で確認するの?John: Why do you confirm each word with the English version?

ユイ: 英語の方がわかりやすいの。

Yui: English terms are much easier to understand.

Maze Navigation | 迷宮ナビ

Let’s break down each scene | それぞれのシーンを理解しよう。Scene 1

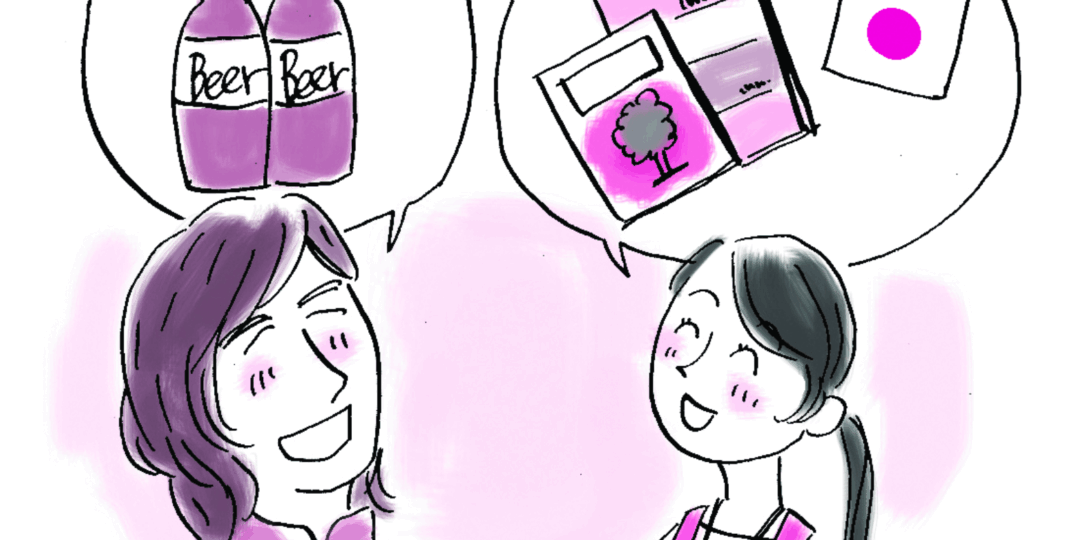

In a cafe, John hands Yui a birthday present, saying in Japanese, “Kore, tannjoubi no okurimono desu.” Nowadays “ba-sudei purezento” is used more frequently than “tanjoubi no okurimono.”

喫茶店。 ジョンはユイに「誕生日の贈り物」と言って箱を手渡します。 今では、「誕生日の贈り物」より、「バースデープレゼント」の方がより使われています。

Keywords:

■ 誕生日 (tanjoubi): birthday ■ 箱 (hako): box ■ 手渡す (tewatasu): hand over / pass

■ 喫茶店 (kissaten): café ■ 〜の方が (〜no hou ga): rather than / is more

Scene 2

John calls that present a kubikazari (neck ornament), but nowadays almost no one uses that word. In Japanese as well, people usually say necklace.

ジョンはそのプレゼントが首飾りといいますが、現在では首飾りという人はほとんどいません。 日本語でもネックレスといいます。

Keywords:

■ 首飾り (kubikazari): necklace ■ 現在 (genzai): now/at present/currently

■ ほとんど (hotondo): almost/hardly/nearl ■ いいます (iimasu): say/call

Scene 3

John invites Yui to have a toast at a shokudo. Shokudo generally refers to a casual, inexpensive eatery, while establishments that serve wine are usually called restaurants. In addition, the word budōshu (“grape liquor”) is now considered old-fashioned; in modern Japanese, the borrowed word wine is commonly used.

ジョンは食堂で乾杯しようとユイを誘います。 「食堂」は一般的に大衆的な飲食店を指し、ワインを提供する店は通常「レストラン」と呼ばれます。 また、「ぶどう酒」という言葉も今では古風な表現であり、日本語でも一般的に「ワイン」という外来語が使われています。

Keywords:

■ 誘う (sasou): invite/ask/suggest ■ 古風 (kofuu): old-fashioned/archaic ■ 一般的 (ippanteki): general/common/typical

Scene 4

John asks Yui why she rephrases these words in English to confirm their meaning. In fact, most of the Japanese words John learned are no longer used in daily life. Today, many English-derived words have taken their place in Japanese.

ジョンはユイに、なぜこれらの言葉を英語に言い換えて確認するのかと尋ねます。 ジョンが学んだ日本語の多くは、もはや日常では使われていません。 今では、その代わりに数多くの英語由来の言葉が日本語として用いられています。

Keywords:

■ 言い換える (iikaeru): rephrase/paraphrase / say differently ■ 由来 (yurai): origin/ derivation/source

Maze Exit| 迷宮出口

What did the punchline reveal? | 今回のオチでわかったことCultural Insight | 新しい発想・文化知識

Lost in Translation: 日本語から英語へ移った言葉

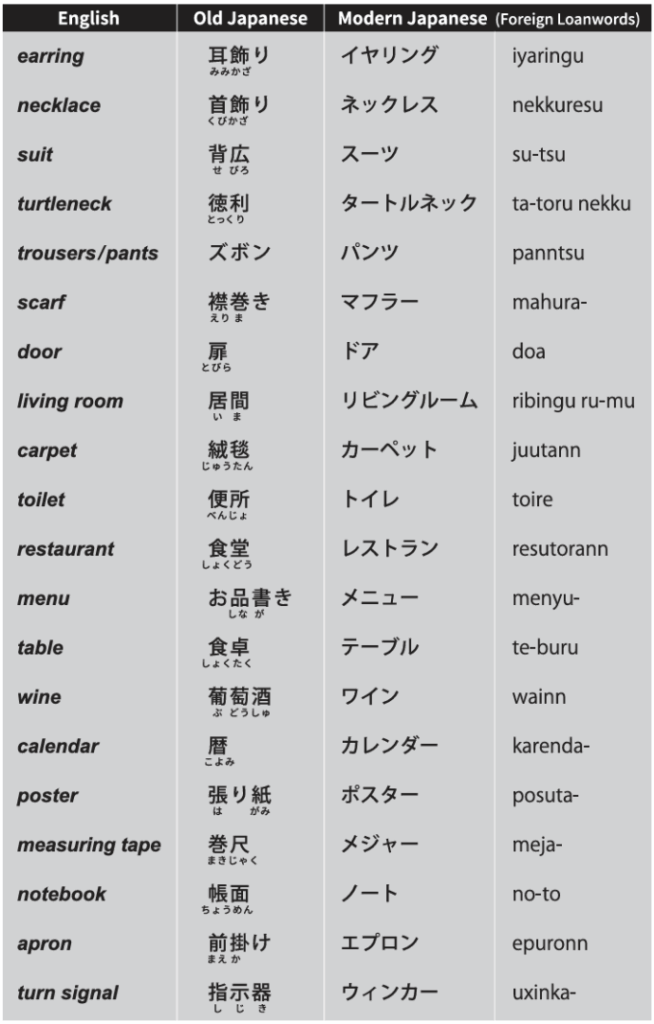

There are various estimates, but according to research by the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics and others, about 10 to 15 percent of the vocabulary used in modern Japanese consists of loanwords, the majority of which are derived from English.

諸説ありますが、国立国語研究所などの調査によると、現代日本語で使われる語彙の約1割〜1.5 割が外来語であり、その大半は英語由来とされています。

In other words, if you are an English speaker, you already naturally know a large part of Japan’ s vocabulary. This reality itself can serve as the foundation for what may be called the “fastest and most effective method” of mastering Japanese.

つまり、あなたが英語話者であれば、すでに日本語の膨大な語彙の一部を自然に知っているのです。 この現実を足がかりにする学習法こそ、「超最短・最速の日本語習得法」といえるでしょう。

This article is from the October 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年10月号より掲載しています。

-

[JAPAN MAZE | 迷宮ニホン – September 2025 Issue]

You may understand the words, but still get lost in communication. This corner takes you on a fun journey through the maze of Japanese language and culture with four-panel manga. Unlocking the punchline is the key — it reveals the essence of Japanese expression and leads you to the exit, with a smile and a fresh insight.

言葉の意味はわかるのに、なぜか通じない――。日本語と日本文化の迷宮を、4コマ漫画で楽しく探検するコーナーです。“オチ”を読み解けば、日本語の本質が見えてくる。迷宮の出口には、気づきと笑いが待っています。

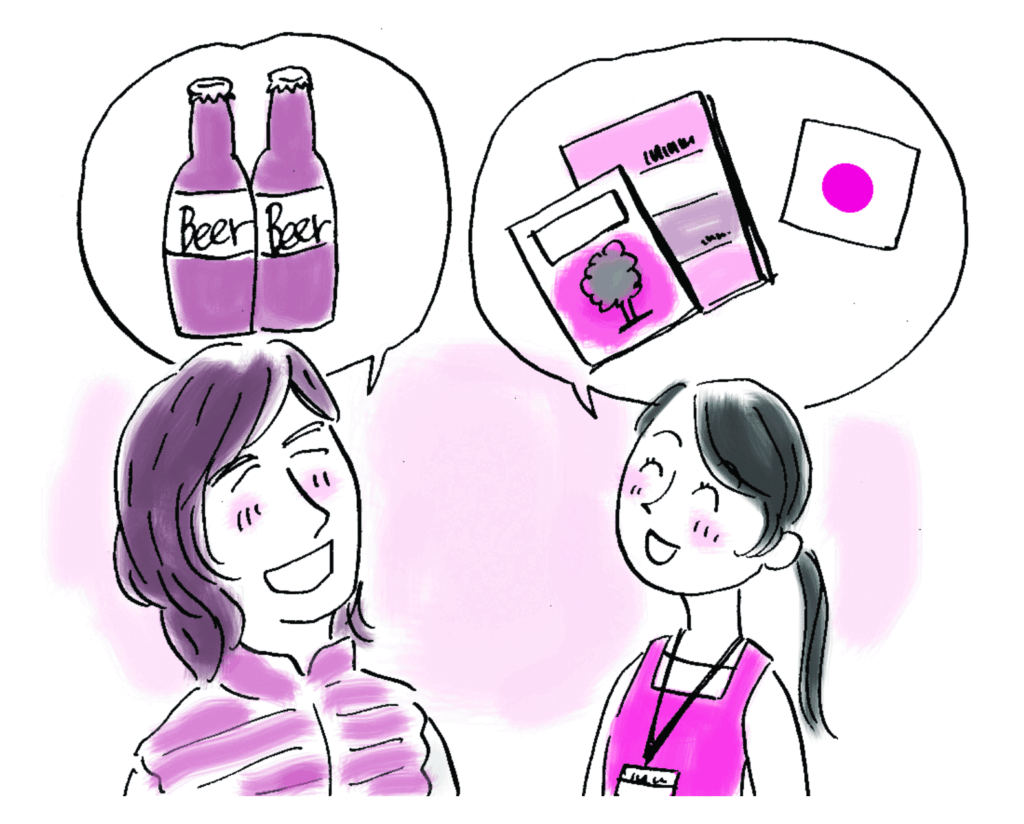

日本を買いたい。| I want to buy Japan.

Scene 1

ティム: ニホン、クレジットカードで買えますか。

Tim: Can I buy ‘nihon’ (two books) with my credit card?

ユリ: え!日本を買うんですか。

Yuri: Wow! You want to buy Japan?

Scene 2

ティム: ツーブックスだから2本でしょう。おかしいですか。

Tim: Two books, so that’s ‘nihon’, am I wrong?

ユリ: 本は冊をつけて数えます。 たとえば、1冊、2冊と。

Yuri: Books are counted by adding “satsu”, for example: ‘issatsu’, ‘nisatsu’.

Scene 3

ティム: ホンと?

Tim: ‘Honto’ (Really)?

ユリ: 「ホン」はビール瓶などに使います。

Yuri: “Hon” is used for things like beer bottles.

Scene 4

ティム: ビール2本は「ニッポン」ですか、「ニホン」ですか。

Tim: For two bottle of beers, do you say “hippon” or “nihon”?

ユリ: あなたはどうしても「にほん」 買いたいのですね。

Yuri: You reallly want to buy “nihon,” dont’ you?

Maze Navigation | 迷宮ナビ

Let’s break down each scene | それぞれのシーンを理解しよう。Scene 1

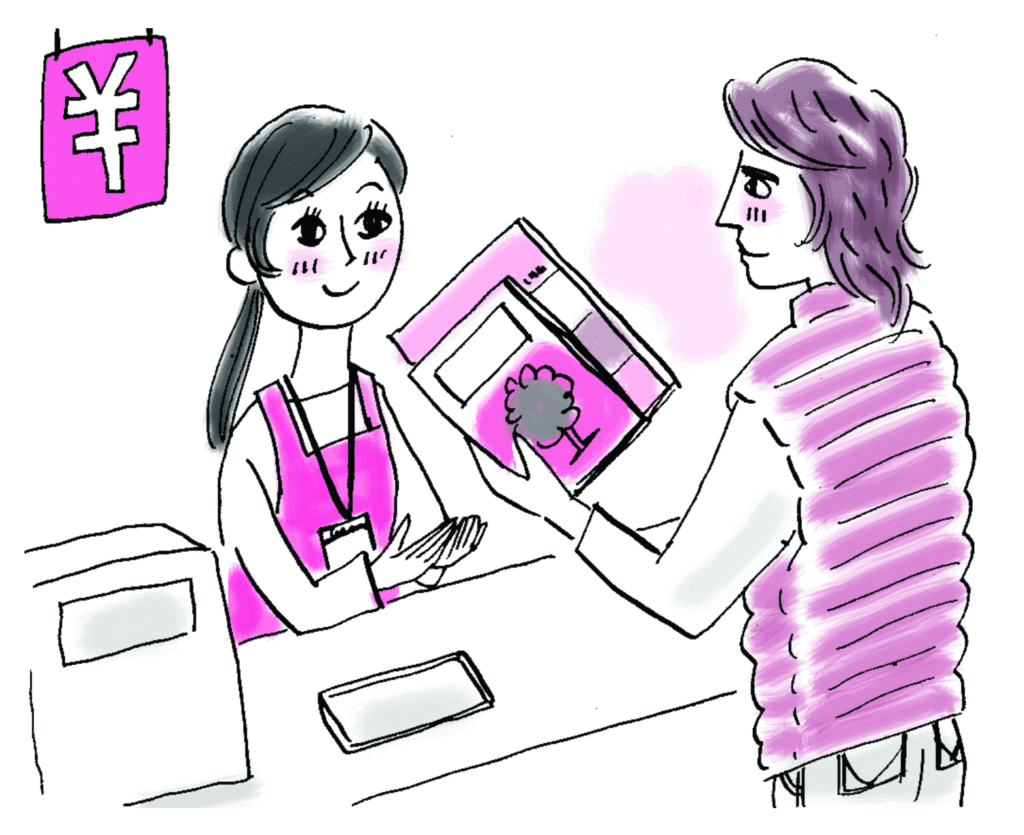

At a bookstore counter, Tim is trying to buy two books. But instead of saying “ni-satsu,” the correct counter for books, he mistakenly says “nihon,” which is used for long objects and Japan.

本屋のカウンターで、ティムが本を2冊買おうとしています。本なら「にさつ」と言うべきところを、間違えて「ニホン(=2本/日本)」と言ってしまいます。

Keywords:

■本屋[bookstore] ■カウンター[counter] ■本[book] ■買う[buy]

Scene 2

Yuri explains that in Japanese, books are counted using “satsu,” and gives examples like “issatsu, nisatsu.”

ユリは、日本語では「冊」を使って本を数えると説明し、「いっさつ、にさつ…」と例を挙げます。

Keywords:

■おかしい [funny, strange] ■挙げる [give (an example)] ■冊 [volume, bound document] ■例 [example]

Scene 3

Hearing this, Tim says “Honto?” — a pun playing on “hon” (book) and “honto” (really?).

それを聞いたティムは、「ホンと?」と言います。「ホン」が入ったダジャレです。

Keywords:

■聞いた [head, listened] ■言う [say, speak] ■ダジャレ [pun]

Scene 4

Tim jokes, “For two beers, is it Nihon or Nippon?” — playing on Japan’s two pronunciations.

ティムは「ビール2本の場合、“ニホン”?“ニッポン”?どっち?」とツッコミます。「日本」の呼び方が二通りあることを踏まえた、彼なりのジョークです。

Keywords:

■どっち [which] ■呼び方 [pronunciation / way of saying] ■ ツッコミ[punchline / quip ] ■二通り [two ways] ■踏まえた [based on / playing on]

Maze Exit| 迷宮出口

What did the punchline reveal? | 今回のオチでわかったことCultural Insight | 新しい発想・文化知識

💡 Do numbers have “shapes”? |「数」には“形”がある?

In English, “two books” and “two bottles” are both simply “two,” but in Japanese, the counter word changes depending on the shape or nature of the item— as in “ni-satsu no hon” (two books), “ni-hon no beer” (two bottles of beer), “ni-hiki no inu” (two dogs), and “ni-wa no tori” (two birds).

英語では “two books” も “two bottles” も “two” で済みますが、日本語では「2冊の本」「2本のビール」「2匹の犬」「2羽の鳥」と、物の形や性質に応じて助数詞が変わります。

This reflects a characteristic of the Japanese language: its sensitivity to how things are perceived. This linguistic nuance also expresses a unique cultural sensibility. For example, long objects (like pens or beer bottles) use the counter “hon,” flat objects (like plates) use “mai,” and small moving animals use “hiki.”

これは、ものをどう見るかに敏感な日本語の特徴であり、文化的な感性が言葉に現れたものです。たとえば、細長いもの(ペン・ビール瓶など)は「本」、平たいもの(皿など)は「枚」、小さくて動くもの(動物など)は「匹」といった具合です。

Furthermore, “hon” is a unique counter whose pronunciation changes with the number. It transforms rhythmically like music: ippon, nihon, sanbon… Similarly, “hiki” changes as ippiki, nihiki, sanbiki, and so on.

しかも、「本」は数によって読み方が変わる不思議な助数詞でもあります。 「いっぽん・にほん・さんぼん…」と、まるで音楽のリズムのように音が変化するのです。同様に、「匹」も「いっぴき・にひき・さんびき」のように変化します。

While the culture of counters is also found in Chinese, Japanese places special importance on sound and rhythm, adding a unique aesthetic sensibility. Counting things correctly may be a shortcut to internalizing the rhythm, sensibility, and culture of the Japanese language.

この助数詞の文化は中国語にも共通するものですが、日本語では音の響きやリズムも大切にされ、独自の美意識が加わっています。正しく数えることは、日本語のリズムや感性、そして文化を体得する近道かもしれません。

This article is from the September 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年9月号より掲載しています。

Information From Hiragana Times

-

February 2026 Issue

January 21, 2026

February 2026 Issue

January 21, 2026 -

January 2026 Issue – Available as a Back Issue

January 15, 2026

January 2026 Issue – Available as a Back Issue

January 15, 2026 -

December 2025 Issue —Available as a Back Issue

November 20, 2025

December 2025 Issue —Available as a Back Issue

November 20, 2025

ジョン: これ、誕生日の贈り物です。

ジョン: これ、誕生日の贈り物です。 ジョン: 首飾りです。

ジョン: 首飾りです。

ジョン: ユイ、どうしていちいち英語で確認するの?

ジョン: ユイ、どうしていちいち英語で確認するの?