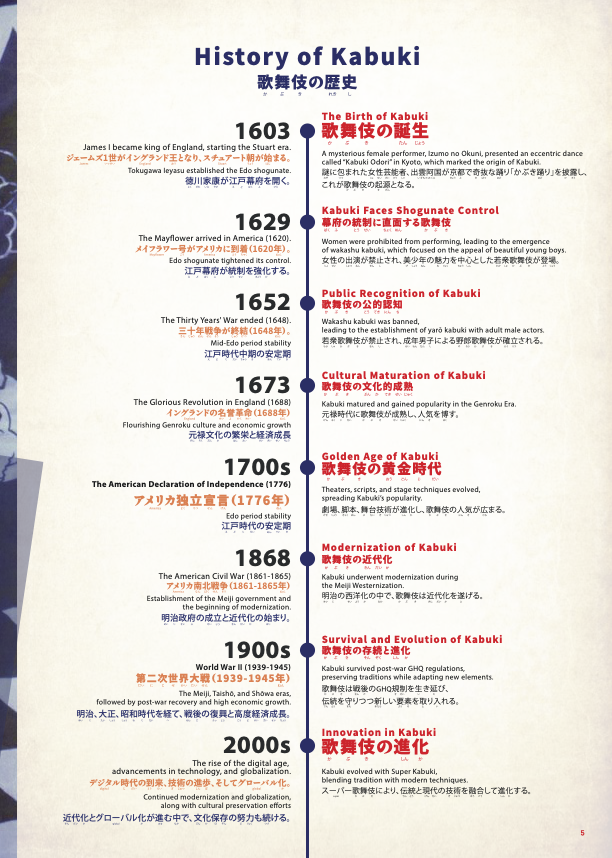

-

[Japan Style – August 2025 Issue]

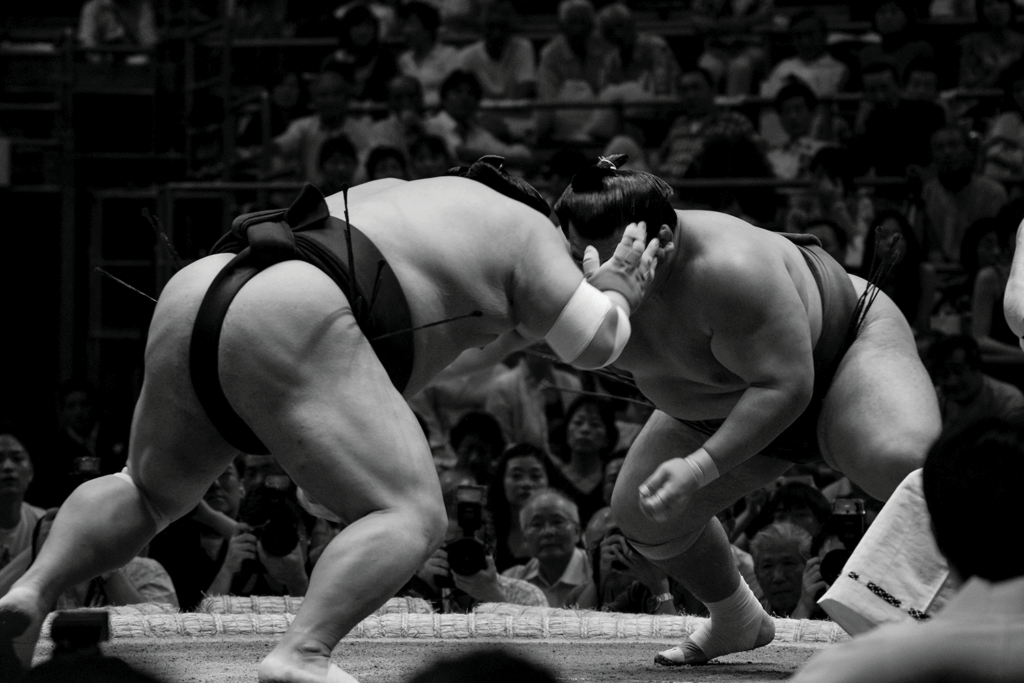

Sumo as a Sacred Ritual: The Divine Contest of Strength that Has Long Protected Japan’s Land

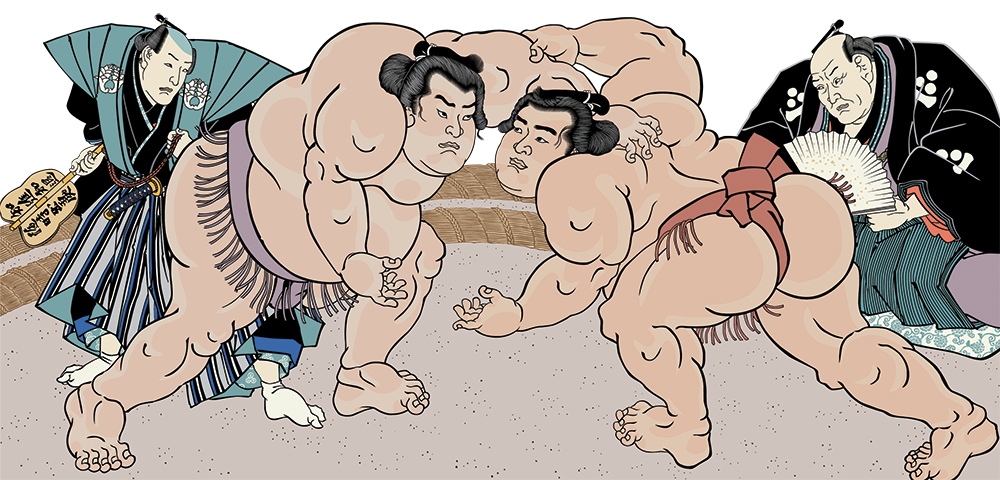

相撲という神事――聖なる力比べが守り続けた日本の大地Sumo is a uniquely Japanese physical art form, in which wrestlers wearing only a ceremonial loincloth (mawashi) clash atop the earthen ring. With bodies forged through spirit and technique, they confront one another not merely in competition, but as a solemn expression of discipline and reverence. Underlying this tradition is a deep-rooted belief: that the human body is a sacred gift from the divine—pure, unarmed, and to be honored as such.

相撲は、廻しを締めた力士が土俵でぶつかり合う、日本独自の身体文化です。力士は廻し一つの姿で土に立ち、精神と技によって鍛え抜かれた身体をぶつけ合います。そこには、身体は神から授かった清らかなものとする考えが根づいています。

The mawashi is not merely a piece of clothing. Like the sacred rope (shimenawa) found at Shinto shrines, it is thick, twisted counterclockwise (to the left), and carries spiritual significance. Hanging from the front are sagari—strips that mark the boundary between the sacred and the secular. The very appearance of the wrestler, clad in this ritual attire, signifies that he stands within a sacred space, embodying the presence of one who enters a realm of divine encounter.

この「廻し」は、単なる衣服ではありません。神社のしめ縄と同じく太く、左撚り(反時計回り)に綯(な)われた神聖な装束であり、前面には神域と俗世を隔てる「さがり」が垂れ下がっています。力士の姿そのものが、神聖な場に身を置く存在であることを物語っています。

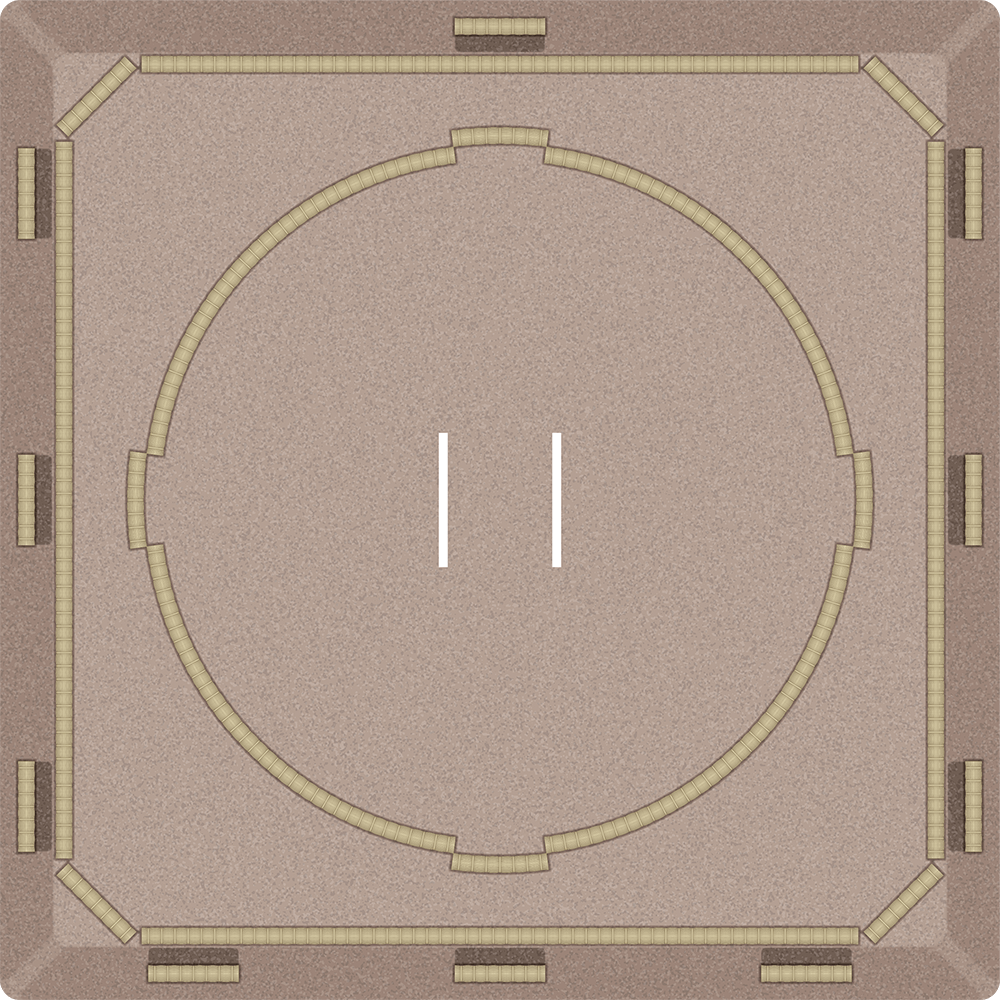

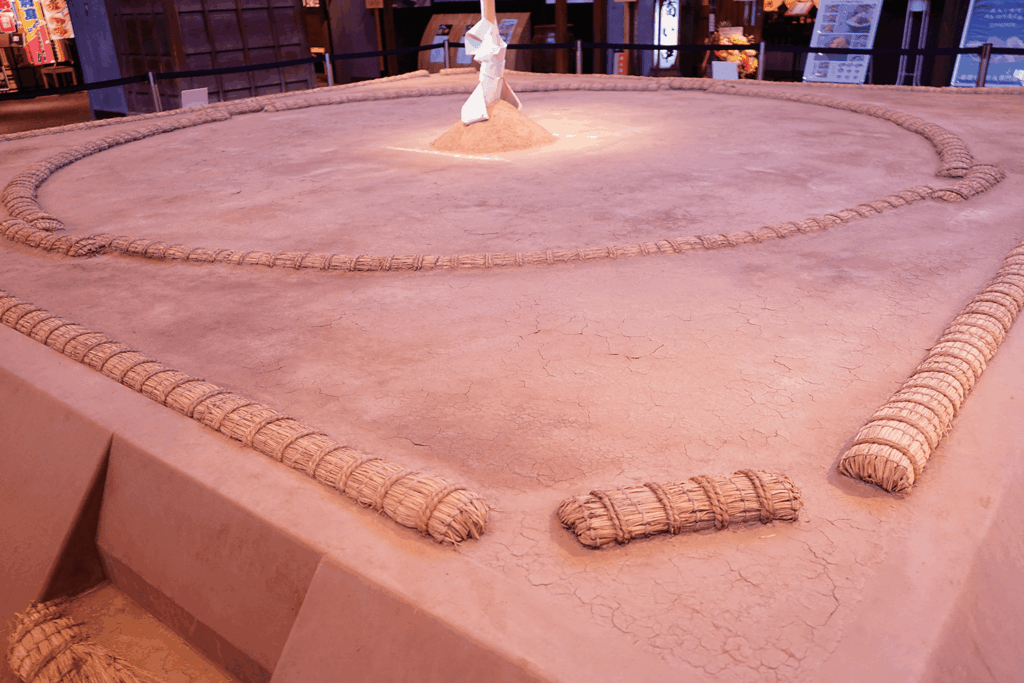

In the world of sumo—aptly called Kakukai, meaning “the square world”—the dohyō (sumo ring) is constructed by firmly packing the earth into a square base. At its center, a perfect circle measuring 4.55 meters (15 shaku) in diameter is outlined with rice-straw bales.

相撲の世界が「角界(かくかい)」と呼ばれるように、土俵は四角く土を突き固めて築かれ、その中央に直径4.55メートル(15尺)の円が俵で描かれています。

In the past, sumo matches were sometimes held on square dohyō without the circular ring we see today. Even now, in regions such as Iwate and Okayama, traditional sumo is still practiced on kaku-dohyō—square rings. Going further back in history, it is said that sumo was performed without any defined ring at all, inside a hitogaki—a naturally formed circle of spectators who gathered around the wrestlers.

かつては四角いままの土俵で取られていたこともあり、今も岩手県や岡山県では「角土俵」による相撲が伝えられています。さらに古くは、土俵という構造自体がなく、観客が自然に円を描く「人垣(ひとがき)」の中で行われていたと伝えられています。

This circular formation is regarded as the prototype of today’s dohyō. Because it allowed the match to be viewed clearly from all four directions—east, west, south, and north—it eliminated blind spots, making it possible to judge the instant a wrestler stepped out with fairness and clarity.

この円形こそが現在の土俵の原型とされ、東西南北どの方向からも見渡せるため「死角」がなく、足が出た瞬間の判定も公正に行えました。

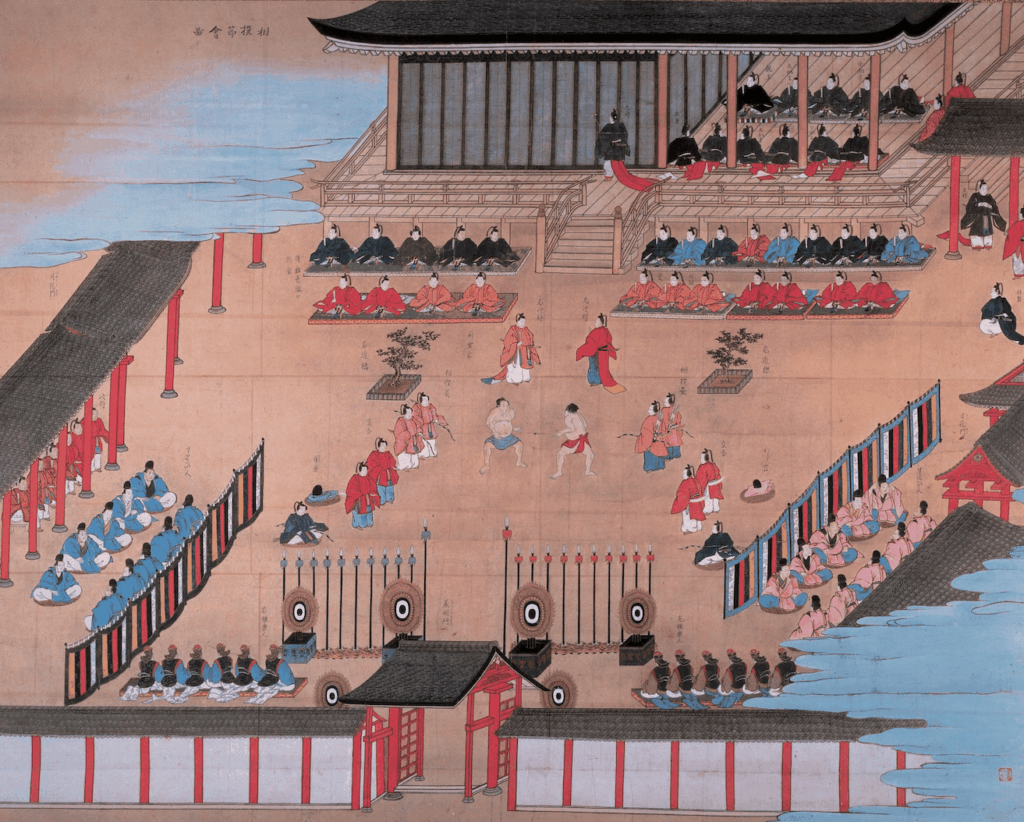

Sumo boasts a history of at least 1,500 years, evolving in form and function over the ages as it has been handed down to the present day. Its origins appear in mythology as a test of strength among the gods, and historical records of sumo first emerge during the Nara period. By the Heian period, it had become an established court ritual known as Sumai no Sechie, held to pray for a bountiful harvest.

Sumo boasts a history of at least 1,500 years, evolving in form and function over the ages as it has been handed down to the present day. Its origins appear in mythology as a test of strength among the gods, and historical records of sumo first emerge during the Nara period. By the Heian period, it had become an established court ritual known as Sumai no Sechie, held to pray for a bountiful harvest.相撲は、少なくとも1500年以上の歴史をもち、時代を追うごとに姿と役割を変えながら、現代へと受け継がれてきました。起源は神々の「力比べ」として神話に登場し、文献上は奈良時代にその記録が現れます。平安時代には、五穀豊穣を願う宮中の祭事「相撲節(すまいのせち)」として定着しました。

During the Warring States period (Sengoku Jidai), sumo was employed as a practical means to assess the strength and skill of retainers. Historical records also note that Oda Nobunaga held sumo matches, demonstrating its significance even in military and political contexts.

During the Warring States period (Sengoku Jidai), sumo was employed as a practical means to assess the strength and skill of retainers. Historical records also note that Oda Nobunaga held sumo matches, demonstrating its significance even in military and political contexts.戦国時代には、家臣の力量を見極める実践的な手段として用いられ、織田信長も相撲を催した記録が残っています。

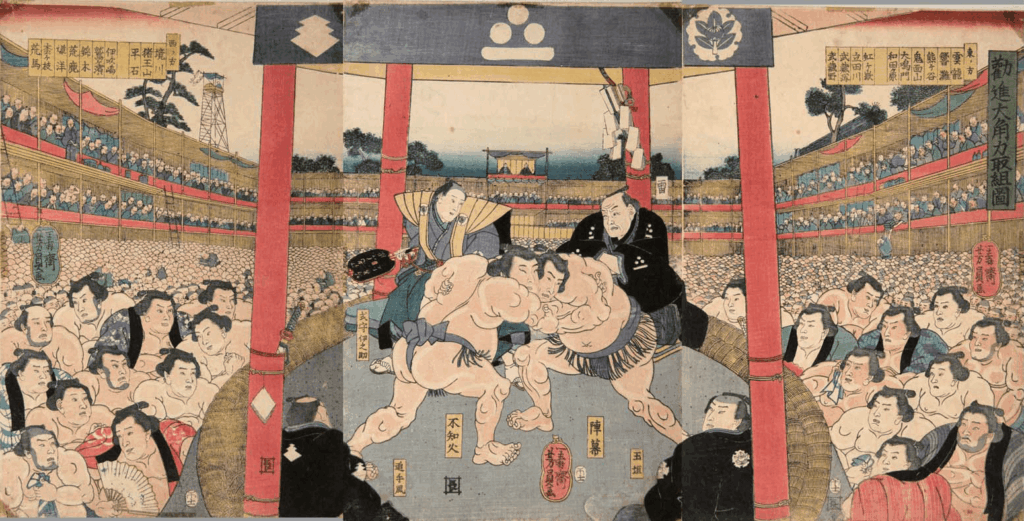

During the Edo period, sumo became a major form of entertainment among the common people, standing alongside kabuki in popularity. It was during this era that the foundations of modern ōzumō (professional sumo) were firmly established.

During the Edo period, sumo became a major form of entertainment among the common people, standing alongside kabuki in popularity. It was during this era that the foundations of modern ōzumō (professional sumo) were firmly established.江戸時代には、歌舞伎と並ぶ庶民の一大娯楽となり、現在の大相撲の原型が形づくられました。

In this way, sumo has never been merely a contest of strength—it has been deeply intertwined with sacred ritual, politics, performing arts, and martial discipline, forming a core part of the Japanese spiritual and cultural identity. Above all, its role as a shinji—a ritual praying for bountiful harvests and national peace—has endured, with hōnō-zumō (dedicatory sumo) still held at shrines throughout Japan today.

In this way, sumo has never been merely a contest of strength—it has been deeply intertwined with sacred ritual, politics, performing arts, and martial discipline, forming a core part of the Japanese spiritual and cultural identity. Above all, its role as a shinji—a ritual praying for bountiful harvests and national peace—has endured, with hōnō-zumō (dedicatory sumo) still held at shrines throughout Japan today.このように相撲は、単なる勝負事ではなく、神事・政治・芸能・武道と深く結びつき、日本人の精神文化の中核を成してきたのです。なかでも、五穀豊穣や国の安寧を祈る“神事”としての性格は今も受け継がれ、奉納相撲は全国各地で続いています。

Even during ōzumō (grand sumo) regional tours, wrestlers step onto local dohyō to stamp the earth, drive out evil spirits, and purify the land. In this sense, sumo serves as a “traveling ritual,” delivering prayers across the country. The spirit of sumo as shinji—a sacred rite—continues to live on today in the wrestlers’ movements and in the very structure of the dohyō itself.

大相撲の巡業でも、各地の土俵で力士が大地を踏み鎮め、邪気を祓い、土地を清める——相撲は“移動する神事”として、日本各地に祈りを届けているのです。こうした“神事”としての相撲の精神は、力士の所作や土俵の構造に今なお息づいています。

🟤 The Ritual Movements of the Rikishi (Sumo Wrestlers) / 力士の所作

-

Scattering Salt — Purifying the Ring and Offering Prayers to the Divine | 塩まき――土俵を清め、神に祈る

Before stepping into the ring, a rikishi scatters salt onto the dohyo. Known as “cleansing salt,” this act is akin to purification rituals performed at Shinto shrines. It serves to ward off evil spirits, sanctify the ground, and offer silent prayers before taking the first step. Each wrestler has their own unique way of casting the salt, making this simple gesture a personal expression of reverence.

力士は土俵に上がる前に塩を撒きます。これは「清めの塩」と呼ばれ、神社で行われるお祓いと同じ意味を持ちます。土俵を清め、邪気を祓い、神への祈りを込めて一歩を踏み出します。取り組みごとに何度も撒かれ、撒き方にも力士ごとの個性があります。

-

-

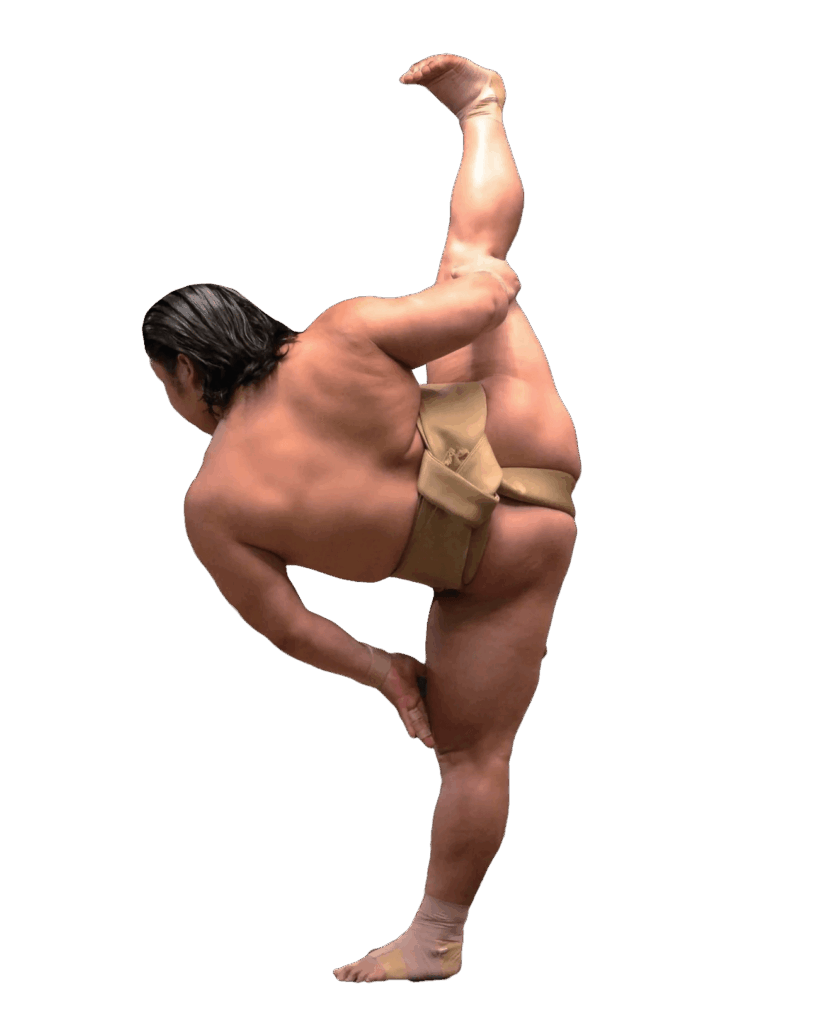

Shiko — Stomping to Suppress Evil Spirits | 四股――邪気を踏み鎮める

One of the most striking movements on the dohyo is shiko, in which a wrestler lifts one leg high and forcefully stomps it down. Since ancient times, this act has symbolized the subjugation of “impure” or evil forces. It is a sacred motion believed to drive out malevolent spirits lurking in the earth and to purify the arena, reaffirming the spiritual foundation of sumo.

土俵上で最も印象的な動作「四股(しこ)」は、片足を高く上げ、力強く踏み下ろす所作です。古くから「醜いもの」を地に封じる意味があり、地中に潜む邪気を鎮め、場を清める神聖な動作とされています。

-

Chikara-mizu and Chikara-gami — Purifying Body and Mind | 力水・力紙――身体と心を清める

Chikara-mizu and Chikara-gami — Purifying Body and Mind | 力水・力紙――身体と心を清める

Before a bout, wrestlers rinse their mouths with chikara-mizu (“power water”), a ritual act similar to the temizu purification performed before entering a Shinto shrine. They then wipe their mouths with a white paper cloth called chikara-gami. Together, these actions serve to cleanse both body and spirit, allowing the wrestler to step onto the dohyo in a state of ritual purity.

取り組み前に口をすすぐ「力水(ちからみず)」は、神事における手水と同様の意味を持ちます。続けて白い「力紙(ちからがみ)」で口を拭うことで、心身を清め、清らかな状態で土俵に臨みます。

-

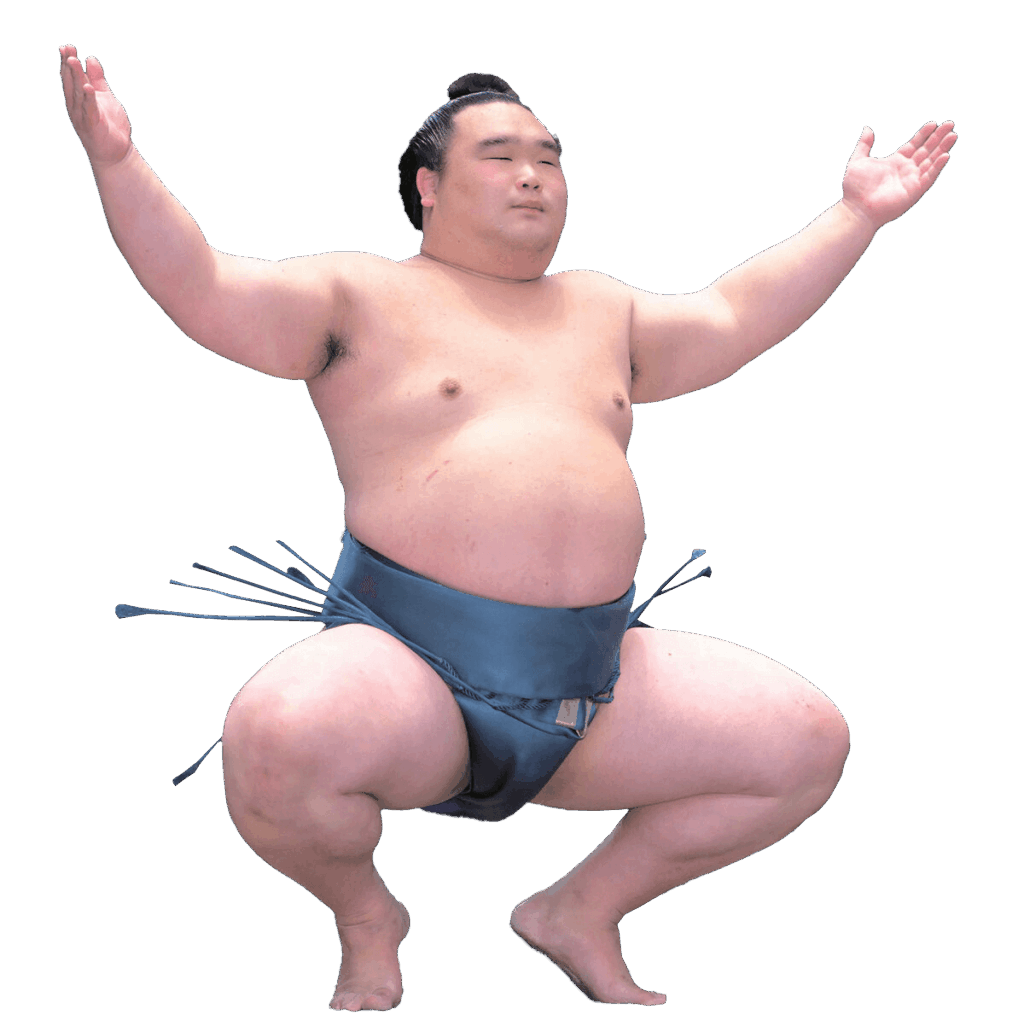

Sonkyo — A Posture of Respect and Readiness | 蹲踞(そんきょ)――敬意と覚悟の姿勢

Sonkyo is the fundamental stance a wrestler assumes upon stepping onto the dohyo. With knees wide apart, back straight, and fingertips resting lightly on the knees while standing on the balls of the feet, this posture embodies both reverence toward the opponent and a calm mental readiness. Seen in traditional martial arts and religious rituals alike, sonkyo is a classic expression of “stillness and respect” in Japanese spiritual culture.

土俵に上がった力士が取る基本姿勢が「蹲踞」。爪先立ちで膝を大きく開き、背筋を伸ばして手を膝に置くこの姿勢は、相手に対する敬意と、心身を整える覚悟の表れです。蹲踞は武道や神事でも見られる「静と礼」の基本姿勢です。

-

Chirichozu — A Vow to Fight Unarmed | 塵手水――刀を持たぬ戦いの誓い

Chirichozu — A Vow to Fight Unarmed | 塵手水――刀を持たぬ戦いの誓い

Chirichozu is the ritual gesture performed after sonkyo, where the wrestler claps his hands, extends his arms, and displays his open palms to the audience. This act purifies the body and spirit while also symbolizing the absence of weapons—a declaration of fair combat. It is a solemn moment in which the wrestler pledges sincerity, respect for the opponent, and readiness to face the match with honor, reflecting the sacred nature of sumo as a ritual rather than mere sport.

蹲踞の後、力士は柏手(かしわで)を打ち、両手を広げて手のひらを見せる所作を行います。これは身の穢れを払い、心を整え、「武器は持っていません」という潔白の証であり、相手への敬意を示す意味も含みます。力士が神と相手、そして自身の内なる誓いに向き合う瞬間でもあります。

-

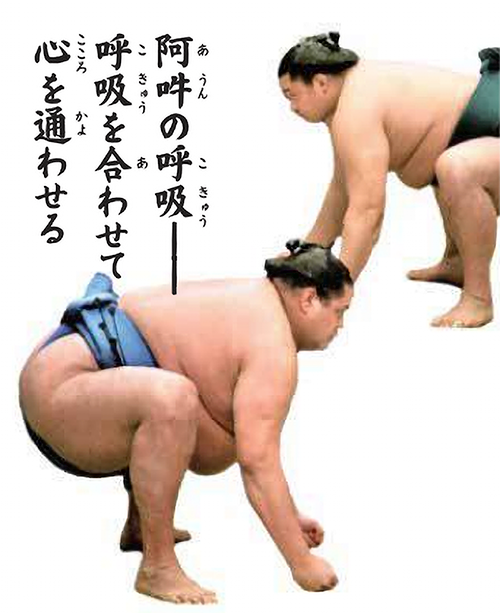

A-un no Kokyū — Harmonizing Breath, Connecting Hearts | 阿吽(あうん)の呼吸――呼吸を合わせて心を通わせる

A-un no Kokyū — Harmonizing Breath, Connecting Hearts | 阿吽(あうん)の呼吸――呼吸を合わせて心を通わせる

The a-un no kokyū—literally “the breath of A and Un”—is a concept rooted in Buddhism, referring to the synchronized breathing between two individuals. In sumo, it is the sacred exchange that takes place at the tachiai (initial charge), as the two wrestlers seek a shared moment of harmony before clashing. Within that intense stillness, their spirits rise, and the moment of release becomes an explosion of stored energy. It is here, in this silent communion, that the spiritual intensity and dramatic power of sumo truly reside.

相撲の立ち合いで求められる「阿吽の呼吸」は、仏教に由来し、呼吸を合わせて心を通わせることで、力士同士が“調和の間”を探る神聖なやり取りです。その静けさの中で気が高まり、蓄えられたエネルギーが一気に解き放たれる――そこにこそ、立ち合いの迫力と神聖さが宿っています。

-

Ring Names and Nature Worship — Invoking the Spirit of Mountains, Seas, Wind, and Sky | 力士の名前と自然信仰――山・海・風・空に宿る力

Ring Names and Nature Worship — Invoking the Spirit of Mountains, Seas, Wind, and Sky | 力士の名前と自然信仰――山・海・風・空に宿る力

Many rikishi adopt ring names (shikona) that include characters like “-yama” (mountain), “-umi” (sea), “kaze” (wind), or “ryū” (dragon)—symbols drawn from nature and the spiritual realm. These names reflect Japan’s ancient tradition of nature worship, or animism, in which all things in the natural world are believed to possess a spiritual essence. In this way, a sumo wrestler’s name becomes more than an identity—it becomes a vessel of sacred power, echoing the forces of nature they embody in the ring.

多くの力士の四股名には「○○山」「○○海」「風」「龍」など、自然や霊的な存在を表す文字が使われています。これは、日本古来の自然信仰(アニミズム)を体現しているとも言えるでしょう。

-

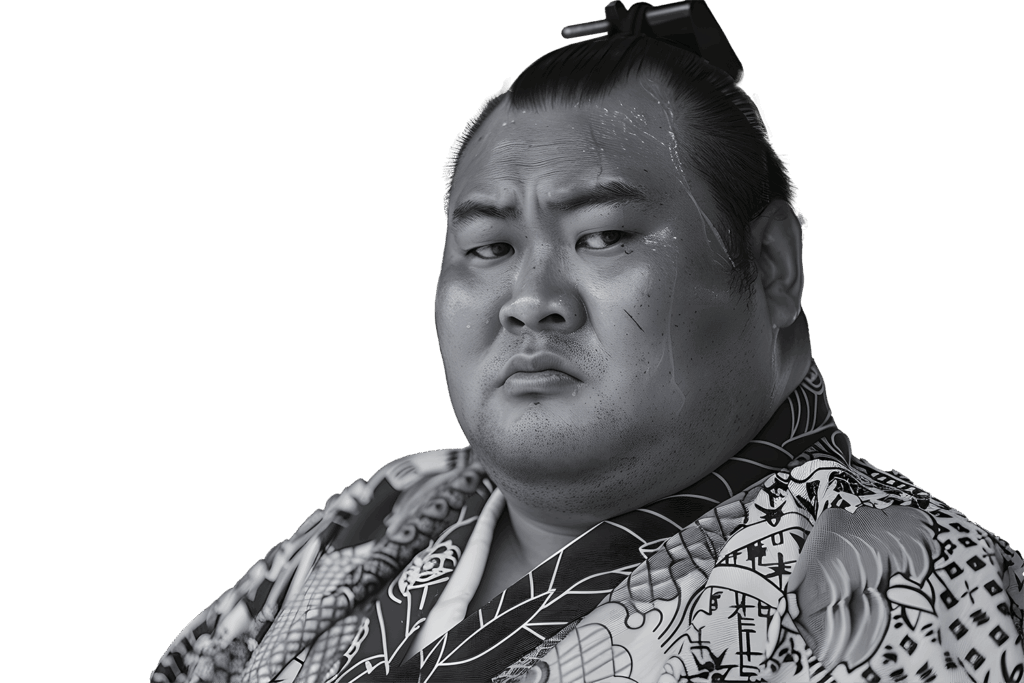

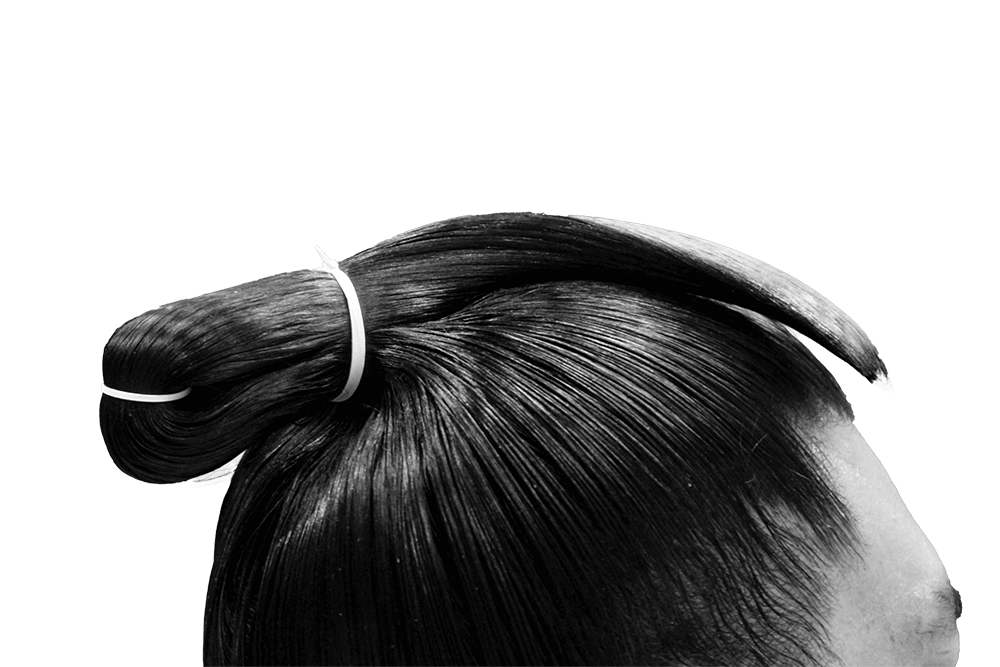

The Topknot (Mage) — A Symbol of Dignity and Sacred Devotion | 髷(まげ)――威厳と祈りを背負う象徴的な姿

The topknot (mage) worn by sumo wrestlers is more than a hairstyle—it is a sacred adornment that embodies the dignity of those who step into the ring. The ōichō (great ginkgo leaf) style, in particular, traces its origins to the samurai of the Edo period and conveys a sense of formality and refinement. As a part of sacred ceremony, the mage signifies the wrestler’s solemn readiness to participate in divine rituals. Upon retirement, a ritual hair-cutting ceremony (danpatsu-shiki) is held, during which the topknot is severed—a powerful moment that marks the close of a wrestler’s career, witnessed with reverence, gratitude, and heartfelt prayers.

力士の髷(まげ)は、神聖な姿を整えるための重要な所作です。なかでも「大銀杏(おおいちょう)」と呼ばれる結い方は、江戸時代の武士に由来し、格式と品格を象徴します。髷は、神事の場に立つ者の威厳と覚悟を示す、神聖な装束でもあります。引退の際には髷を切り落とす断髪式が行われ、その人生の節目を多くの人が見届け、労いと祈りを捧げます。

🟤 The Dohyō and Its Symbolism 土俵とその象徴性

-

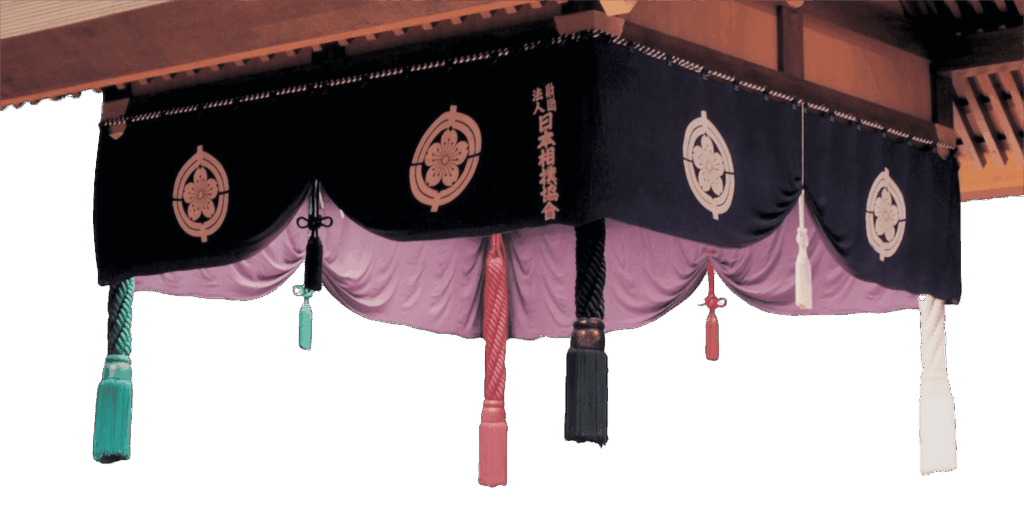

Tassels and the Four Guardian Deities — Protectors of the Sacred Ring | 房(ふさ)と四神――土俵を守る神々

Hanging from the four corners of the dohyō canopy are colored tassels—blue (green), red, white, and black—each symbolizing a season and a celestial guardian of direction:

Blue (Green) – Spring, protected by the Azure Dragon (Seiryū) of the East

Red – Summer, protected by the Vermilion Bird (Suzaku) of the South

White – Autumn, protected by the White Tiger (Byakko) of the West

Black – Winter, protected by the Black Tortoise (Genbu) of the North

This symbolizes that the dohyō is a sacred space.

土俵の屋根四隅に垂れる青(緑)・赤・白・黒の「房」は、以下を象徴しています。

青(緑)…春 東を守護する青龍

赤…夏 南を守護する朱雀

白…秋 西を守護する白虎

黒…冬 北を守護する玄武

これは、土俵が神域であることを表しています。

-

The Dohyō as a Mandala — A Sacred Microcosm of the Cosmos and Deities | 土俵は曼荼羅的空間――宇宙と神仏の縮図

The Dohyō as a Mandala — A Sacred Microcosm of the Cosmos and Deities | 土俵は曼荼羅的空間――宇宙と神仏の縮図

The dohyō (sumo ring) embodies traditional Japanese spatial philosophy: the circle represents infinity, while the square symbolizes stability. This structure reflects the design logic seen in Buddhist mandalas—cosmic diagrams that express the order of the universe. The dohyō is not just a ring, but a sacred space that connects heaven and earth, the four directions, and the divine.

「円は無限」、「四角は安定」。土俵は、こうした伝統空間論に基づいた構造をもちます。仏教の曼荼羅(宇宙図)にも通じ、天地四方を意識した、神仏とつながる神聖な空間です。

-

Dohyō Matsuri — The Ritual of Inviting the Divine | 土俵祭(どひょうまつり)――土俵に神を迎える儀式

Before the start of each official tournament, a sacred ceremony known as Dohyō Matsuri is performed. Shinto priests and sumo referees (gyōji) gather to consecrate the ring by burying offerings such as salt, rice, kelp, dried squid, and sake into the center of the dohyō. This ritual symbolizes that the ring is not merely a venue for sport, but a sacred space prepared to welcome the presence of the divine.

本場所の初日前には「土俵祭」が行われ、神職や行司が立ち会い、塩・米・昆布・スルメ・酒などを土俵に埋めて神を招き入れます。土俵が“神を迎える場”として扱われていることの象徴です。

🟤 The Yokozuna and the Sacred Rituals 横綱と儀式性

-

The Yokozuna as a Sacred Presence — A Vessel of Divine Power | 神聖な存在、横綱――神の力を体現する存在

The ceremonial rope (tsuna) worn by a yokozuna mirrors the shimenawa found at Shinto shrines, signifying the yokozuna’s status as a sacred being. As the highest-ranked wrestler, the yokozuna serves as a living vessel (yorishiro) for divine spirits.

横綱が締める綱は、神社のしめ縄と同じく、神聖な存在であることの証とされています。横綱は人の姿を借りた神の依り代としての役割を担っています。

-

The Yokozuna Ring-Entering Ceremony — A Ritual Dance Dedicated to the Divine | 横綱土俵入り――神前に捧げる神事の舞

During the dohyō-iri (ring-entering ceremony), the yokozuna performs one of two ritual forms—Unryū or Shiranui—movements believed to ward off evil spirits. Accompanied by attendants (the sword bearer and dew sweeper), the yokozuna’s solemn entry into the ring is a sacred offering performed before the divine.

横綱が土俵入りで見せる型(雲龍型・不知火型)は、悪霊を払う祈りの舞とも言われます。露払い、太刀持ちを従えた儀式的な登場は、まさに神前で行われる奉納の儀です。

-

Bows to the Four Directions — A Gesture of Harmony with Heaven and Earth | 四方への礼――天地四方とのつながりを示す所作

As part of the ring-entering ceremony, the yokozuna and the referee bow toward the four cardinal directions. This act expresses reverence and prayer to the heavens, the earth, and the four corners of the world—symbolizing connection with the cosmic order.

土俵入りの際、横綱や行司が行う「四方に向かっての礼」には、東西南北・天地に向けて敬意と祈りを示す意味が込められています。

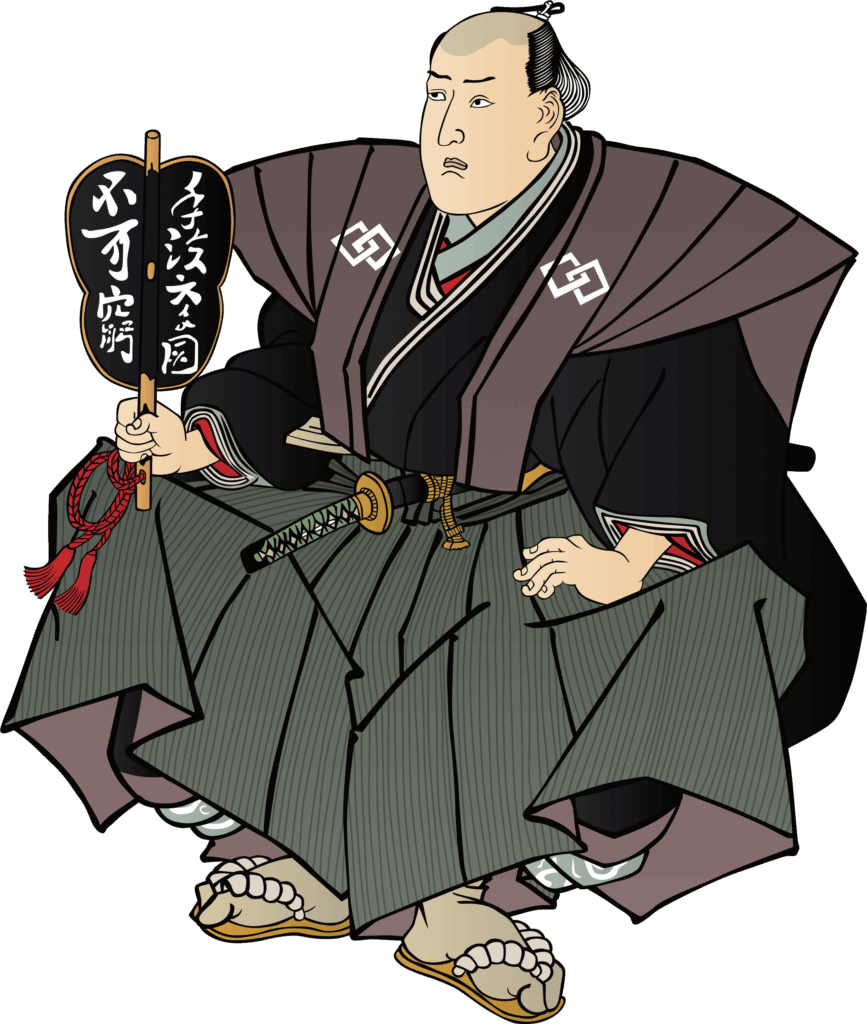

🟤 The Gyoji and the Sacred Nature of Judging | 行司と勝負の神聖性

-

The Gyoji’s Attire — Carrying on the Robes of a Shinto Priest | 行司の装束――神職の姿を受け継ぐ役目

The gyoji (sumo referee) dons traditional garments such as the eboshi hat and hitatare robe, resembling the attire of a Shinto priest. The war fan (gunbai) held by senior gyoji symbolizes divine judgment, representing their sacred role in determining the victor.

行司は烏帽子をかぶり、直垂という装束を身につけ、まるで神社の神職のような姿をしています。高位の行司が持つ軍配団扇は神への裁きにも通じ、神聖な勝敗の判定を行う役割を象徴します。

-

The War Fan and Sacred Judgments — Decisions Guided by the Divine | 軍配と勝負審判――神の視点を意識する判断

The War Fan and Sacred Judgments — Decisions Guided by the Divine | 軍配と勝負審判――神の視点を意識する判断

The gunbai once symbolized a retainer of a warrior deity, and its use in sumo retains a ritual meaning. When a match decision is contested, the ensuing mono-ii (discussion) among judges is not merely procedural—it reflects a careful effort to reach a decision that aligns with the will of the divine.

行司が手にする軍配は、かつて武神に仕える者の象徴とされ、神事的な判定の道具でもありました。判定に異議が出た際の「物言い」や「協議」もまた、“神意に沿う”裁きを導くための慎重な合議として受け継がれています。

Interestingly, sumo is not legally designated as Japan’s national sport.

This contrasts with countries like South Korea, where Taekwondo is officially recognized by law as the national martial art, or Mongolia, where Bökh (traditional wrestling) holds that status. Similarly, Chile’s rodeo and Brazil’s capoeira are formally acknowledged as national cultural heritages by their governments.

興味深いことに、相撲は「日本の国技」として法律で定められているわけではありません。韓国のテコンドーやモンゴルのブフ、チリのロデオ、ブラジルのカポエイラなどが、いずれも法令で「国技」や「国家文化遺産」として公式に認定されているのとは対照的です。

However, Japan has no legal framework to formally designate a “national sport.” Even the national flag and anthem were only codified into law as recently as 1999. And yet, many Japanese naturally regard sumo as the national sport. This shared perception reflects a long-standing, unspoken cultural consensus that has quietly taken root over centuries.

しかし、日本には「国技」を法的に定めた制度は存在しません。国旗や国歌ですら、法令で明文化されたのは1999年と、ごく最近のことです。それでも、相撲を「日本の国技」と自然に受けとめる感覚は、多くの人に共有されています。そこには、長い歴史のなかで育まれてきた“無言の文化的合意”があるからです。

Rather than relying on systems or words, the Japanese spirit has long found expression in daily life through prayer, gratitude, and harmony with nature.

This unique cultural mindset flows quietly through the background of sumo as well.

Now more than ever, it may be time for us, the Japanese, to reconsider the true value of such a culture—one that has been passed down not through explanation, but through quiet transmission.制度や言葉に頼らず、祈りや感謝、自然との調和を日々の営みに込める——。

そうした日本独自の精神文化が、相撲の背景にも脈々と流れています。そうした“語らずとも伝わってきた文化”に、今こそあらためてその価値を見つめ直すことが、私たち日本人に求められているのではないでしょうか。Now, as we reexamine sumo through the lens of a sacred rite, what emerges is a reflection of Japan’s past, present, and future— clashing within the sanctified circle of the dohyō. In that moment—what do you see?

今、相撲を、“神事”として見つめ直すとき、そこには、土俵という聖域でぶつかり合う日本の「現在・過去・未来」の姿が浮かび上がってきます。その瞬間 ――あなたは、そこに何を見出しますか?

This article is from the August 2025 issue of Hiragana Times.

この記事は、月刊誌『ひらがなタイムズ』2025年8月号より掲載しています。

-

-

Japan: A Nation of Addition, Multiplication, and Harmony | 足して、掛けて、和する国、日本

[Japan Style – February 2025 Issue]

In the United States, over 240 million people, accounting for about 70% of the population, identify as Christians, and there are approximately 120,000 churches.

アメリカでは、人口の約70%にあたる2億4,000万人以上がキリスト教徒であり、教会の数はおよそ12万にも上ります。On the other hand, Japan, with a total population of about 120 million, roughly 2/5 that of the United States, and a land area just 1/26 of the size, has approximately 165,000 shrines and temples. Furthermore, when including smaller shrines attached to major ones, the number of shrines is said to exceed 300,000.

一方、日本は総人口が約1億2,000万人とアメリカの約2/5であり、国土面積に至っては1/26程度と大幅に小さいにもかかわらず、約16万5,000の神社仏閣が存在します。さらに、神社においては、主要な神社に付属する小規模な神社を含めるとその数は30万社以上に達すると言われています。Shrines are facilities where the deities of Japan’s indigenous Shinto religion are enshrined, and rituals are performed, while temples (Buddhist temples) house Buddhist statues and conduct Buddhist ceremonies.

神社は日本固有の神道の神々を祀り神事を行う、寺(仏閣)は仏像を祀り仏事を行う施設です。The history of shrines is older than that of temples, dating back to the 5th to 3rd centuries BCE. Before the arrival of Buddhism, mountains, forests, rivers, and rocks themselves were revered as sacred and became objects of worship.

神社の歴史は寺よりも古く、紀元前5~3世紀までさかのぼるとされています。仏教が伝来する以前、日本では山や森、川、岩など、自然そのものが神聖視され、崇拝の対象とされていました。This practice, known as animism, later merged with Buddhism, forming a unique Japanese religious system called Shinbutsu-shūgō (the syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism) that endured for over 1,000 years.

これが自然崇拝(アニミズム)であり、この土着信仰に仏教が融合し、神仏習合という形で1000年以上にわたり日本独自の信仰体系が形成されてきました。However, with the Meiji Restoration in 1868 and the enactment of the Shinbutsu Bunri (Separation of Shinto and Buddhism), shrines and temples were formally divided, resulting in the independent institutions we see today.

しかし、明治維新(1868年)の神仏分離令により、神社と寺は分離され、現在のようにそれぞれ独立した施設として存在するようになりました。During the Jomon period, which was centered around hunting and gathering, it is believed that a peaceful and prosperous society flourished for over 10,000 years.

狩猟が中心だった縄文時代には、1万年以上にわたり平和で繁栄した社会が築かれていたと考えられています。The descendants of the sun goddess Amaterasu, known as the Tenson clan (migratory people), sought to claim this land.

この地を、天照大神を祖とする天孫族(渡来系民族)が手に入れようとしました。At that time, the region was governed by the land of Izumo, and Amaterasu Ōmikami sent emissaries many times. However, some of the emissaries were so captivated by the richness and allure of the land that they ended up staying there, and negotiations did not proceed as intended.

当時その地を統括していたのは出雲の国であり、天照大神は何度も使者を送りました。しかし、使者たちはその地の豊かさや魅力に心を奪われてそのまま居着いてしまうこともあり、交渉は思うように進みませんでした。Ultimately, Amaterasu sent Takemikazuchi-no-Mikoto and Futsunushi-no-Okami, gods of war, to negotiate by demonstrating their power. As a result, a peaceful transfer of the land was achieved, avoiding conflict.

最終的に、天照大神は戦いの神である武甕槌命と経津主大神を送り、力を見せつける形で交渉を行いました。結果、争いを避けた平和的な国譲りが実現しました。Takemikazuchi-no-Mikoto and Futsunushi-no-Ōkami, who played key roles in this negotiation, were later enshrined in Kashima Jingū (then known as Kashima Shrine) and Katori Jingū (then known as Katori Shrine), respectively.

この交渉で活躍した武甕槌命と経津主大神はその後、鹿島神宮(当時の鹿島社)と香取神宮(当時の香取社)にそれぞれ祀られることになりました。Kashima Jingū (in Kashima City, Ibaraki Prefecture) and Katori Jingū (in Katori City, Chiba Prefecture) have a Kanameishi (keystone), which is believed to have the power to calm earthquakes. This Kanameishi is a massive natural stone buried deep underground and has been revered by ancient people.

鹿島神宮(茨城県鹿島市)と香取神宮(千葉県香取市)には、地震を鎮める力があるとされる要石が存在します。この要石は地中深くまで埋まっている巨大な自然石で、古代の人々に崇められてきました。Additionally, Kashima Jingū also enshrines Ōkuninushi-no-Mikoto, who was the counterpart in the land transfer negotiations. In addition to calming earthquakes, it plays an important role alongside the gods who brought peace, supporting the peace and order of all Japan.

さらに、鹿島神宮には国譲りの相手であった大国主命も祀られています。地震の鎮静だけでなく、平和をもたらした神々と共に、日本全体の平和と秩序を支える存在として重要な役割を果たしています。

The Tenson clan gained governing authority through the land transfer, but their effective control did not immediately extend across all of Japan. Indigenous clans and powers were still scattered across the Japanese archipelago, and the Yamato region (modern-day Nara) was especially known as a politically and geographically important hub.

天孫族は、国譲りによって統治権を受け取ったものの、その実効力は即座に日本全土に及ぶことはありませんでした。依然として、土着の豪族や勢力が日本列島各地に分散しており、特に大和地方(現在の奈良)は、政治的にも地理的にも重要な拠点として知られていました。Thus, Amaterasu Ōmikami entrusted her grandson Ninigi-no-Mikoto with the Three Sacred Treasures and initiated new governance over the Japanese archipelago. Ninigi-no-Mikoto established his base in the land of Takachiho, consolidating his power and laying the foundation for governance.

そこで、天照大神は孫の瓊瓊杵尊に三種の神器を託し、日本列島での新たな統治を開始させました。瓊瓊杵尊は高千穂の地を拠点に勢力を固め、統治の基盤を築きました。Later, during the era of his great-grandson Iwarebiko, efforts to expand governance further led to a campaign eastward toward the Yamato region. Yamato, with its vast plains suitable for agriculture, had long been a land of powerful clans and was a key region for extending the Tenson clan’s governance across Japan.

そして、曽孫[ひまご]にあたるイワレビコの時代になると、統治をさらに拡大しようと大和地方を目指して東に進軍します。大和は平地が広がり農業にも適しており、古くから豪族たちが力を持つ土地一つで、天孫族の統治を日本全土に広げる鍵となる土地だったのです。After three failed attempts, on the fourth attempt, they were guided by a figure (or clan) known as Yatagarasu, and finally defeated Nagasunehiko, who ruled over the Nara region, successfully conquering the land.

3度の失敗を経て、4度目の試みで八咫烏と呼ばれる人物の導きに助けられ、ついには奈良の地を支配していた長髄彦に勝利し、奈良の地を征服しました。Yatagarasu is known as a three-legged being and is now the symbol of the Japan Football Association. Additionally, some believe that the image of this three-legged crow represents an elderly person with a staff, symbolizing “wisdom,” “experience,” and “spiritual guidance.”

「八咫烏」は3本の足を持つ存在として知られ、現在では日本サッカー協会のシンボルにもなっています。また、この3本の足を持ったカラスの姿は、「知恵」「経験」「霊的な導き」を象徴する杖をついた老人を指しているのではないかと考える人もいます。Having conquered the land of Yamato, Iwarebiko ascended the throne as Emperor Jimmu, the first emperor of the Yamato Court. This event is traditionally dated to January 1, 660 BCE (according to the lunar calendar). From that day to the present 126th Emperor, Reiwa Tennō, the Japanese imperial line has been passed down as a single unbroken lineage.

こうして大和の地を征服したイワレビコは、ヤマト王権の初代天皇である神武天皇として即位します。その時期は紀元前660年1月1日(旧暦)とされています。この日から現在の第126代令和天皇に至るまで、日本の天皇は一つの血統として受け継がれてきました。The Three Sacred Treasures entrusted by Amaterasu Ōmikami to the Tenson clan (Ninigi-no-Mikoto) consist of the Yata-no-Kagami, representing “wisdom”; the Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi, representing “military power”; and the Yasakani-no-Magatama, representing “spiritual power.” The emperor has always carried these treasures as symbols of authority and used them to govern the nation.

天照大神が天孫族(瓊瓊杵尊)に託した三種の神器は、「知力」を司る八咫鏡、「武力」を司る草薙剣、そして「霊力」を司る八尺瓊勾玉(やさかにのまがたま)から成ります。天皇はこれらの神器を常に携え、国家統治を行ってきました。However, during the reign of the 10th Emperor, Emperor Sujin, a series of epidemics and disasters occurred, and it was decided that the spiritual power of the sacred treasures was too strong, leading to their being enshrined separately.

しかし、疫病や災害が相次いだ第10代崇神天皇の時代に、神器の霊力が強すぎるとして神器は分散して祀ることになりました。The Yata-no-Kagami was moved to Ise Jingū as a symbol of Amaterasu Ōmikami. The Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi was used during the reign of the 12th Emperor, Emperor Keikō, by his son, Ōusu, to suppress rebellious local clans and foreign forces, thereby strengthening governance.

八咫鏡は天照大神の象徴として伊勢神宮に移されました。草薙剣は、12代景行天皇の時代に、その息子である小碓が地方豪族や異民族などの反乱勢力を平定し、統治を強化する際に使用されました。Ōusu was given the name Yamato Takeru as a brave figure who unified Japan, and after his death, the Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi was enshrined at Atsuta Shrine in Aichi Prefecture.

小碓は日本を統一した勇猛な人物としてヤマトタケルと名付けられ、彼の死後、草薙剣は愛知県の熱田神宮に祀られました。In this way, only the Yasakani-no-Magatama remained with the emperor and is still kept in the Imperial Palace today.

こうして、八尺瓊勾玉だけが天皇の手元に残り、現在も皇居内で保管されています。

As Japan developed into a unified nation, the spread of wet rice cultivation progressed, enabling a stable food supply. As a result, the population, estimated to have been around 200,000 to 260,000 during the mid-Jomon period (around 3000 BCE), is believed to have grown to 1 to 1.5 million by the late Yayoi period.

統一国家へと発展した日本は水田稲作の普及が進み、安定した食料供給が可能となりました。その結果、縄文時代中期(紀元前3000年頃)には推定20~26万人程度とされる人口が、弥生時代後期には100~150万人に達したと考えられています。Subsequently, irrigation projects aimed at developing rice fields advanced, and the soil excavated during these efforts was used to construct burial mounds. During the Kofun period, the population is estimated to have reached 4 to 5 million.

その後も、稲作地開墾を目的に灌漑事業が進み、その際に出た土を用いて古墳が作られるようになりました。古墳時代には人口400~500万人に達したと推測されています。Shrines were also deeply connected to the development of rice cultivation and spread throughout the country. For example, Inari shrines, with Fushimi Inari Taisha as their main shrine, number approximately 30,000 across Japan and are widely revered as shrines dedicated to the deity of rice (ine).

神社も稲作の発展と深く結びつき、全国に広がっていきました。例えば、伏見稲荷大社を総本宮とする稲荷神社は日本全国に約3万社あり、「稲(米)」の神様として広く信仰されています。Shrines are adorned with shimenawa, which symbolize thunderclouds, and these ropes are accompanied by bells and strands of rope. The white paper strips (shide) hanging from the shimenawa are jagged in shape, representing lightning. Additionally, the straw hanging from the shimenawa symbolizes rain, representing the natural phenomena essential for rice cultivation.

神社には雷雲を象徴する「しめ縄」が飾られており、そこには鈴と縄が付いています。しめ縄にぶら下がる白い紙垂は稲妻を表すギザギザの形をしています。また、しめ縄から垂れるワラは雨を象徴し、稲作に必要な自然現象を表しています。Since ancient times, years with frequent thunderstorms have been considered years of good harvests. For this reason, people visiting shrines would view the ropes hanging from the shimenawa as pillars of clouds and shake these ropes and bells to “create thunder,” praying for a bountiful harvest.

古来より雷が多い年は豊作とされてきました。そのため、神社を訪れる人々は、しめ縄から垂れる縄を雲の柱を見立て、その縄と鈴を揺らし「雷」を鳴らすことで豊作を祈りました。Nitrogen (N₂) in the air is a component that serves as fertilizer for plants, but plants cannot directly absorb it from the atmosphere. However, when lightning occurs, the components in the air are broken down, and nitrogen (N₂) dissolves into the soil along with rain, becoming fertilizer.

空気中には含まれる窒素(N₂)は植物の肥料となる成分ですが、植物は空気中から直接取り込むことができません。しかし、雷が発生すると空気中の成分が分解され、窒素(N₂)が雨とともに土壌に溶け込んで肥料となります。Nitrogen is an essential nutrient for crop growth and is still used as a component of chemical fertilizers today. In ancient times, people regarded lightning as the “wife of rice.” They had discerned the mechanisms of nature.

窒素は作物の成長に欠かせない栄養素であり、現代でも化学肥料として利用されています。古代の人々は稲妻を「稲の妻」と捉えていました。自然のメカニズムを見抜いていたのです。Shrines were not only places to pray for bountiful harvests but were also built in safe locations, such as on mountains, in disaster-prone Japan and were used for storing rice and cultivating or distributing seedlings. They also functioned as hubs connecting the central imperial court with local regions.

神社は豊作を祈る場であるだけでなく、災害の多い日本では山の上など安全な場所に建てられ、米の保管や苗の栽培・配布を行う場としても利用されてきました。また、中央の朝廷と地方をつなぐハブとしても機能しました。The “shrine network” is thought to have played a role in gathering information on regional economic and disaster conditions, thereby supporting a sense of unity across the nation.

「神社ネットワーク」は各地の景気や災害状況の情報を集約し、国家の一体感を支える役割を果たしていたと考えられます。

It is astonishing that such advanced knowledge and systems existed in ancient times, and it could even be said that ancient people may have understood the mechanisms of earthquakes.

こうした進歩的な知識やシステムが古代から存在していたことに驚かされますが、さらに言えば、古代の人々は地震のメカニズムさえも理解していた可能性があります。The Japanese archipelago is traversed by a massive fault line called the Median Tectonic Line, which stretches from the Kanto region to Kyushu. This fault has frequently caused large earthquakes. Located at what is believed to be the starting point of this fault is Kashima Jingū, which houses the Kanameishi, a stone believed to possess the power to calm earthquakes.

日本列島には、関東地方から九州地方にかけて広がる中央構造線という巨大な断層があります。この断層はたびたび大きな地震を引き起こしてきました。その起点とされる場所にあるのが、地震を鎮める力を持つと信じられてきた要石を擁する鹿島神宮です。How people in ancient times, without geological surveying tools, came to recognize the importance of this location remains a mystery to this day. Furthermore, Kashima Jingū is not only a shrine believed to calm earthquakes but also enshrines deities who brought peace through military strength, symbolizing peace and order throughout Japan.

地質調査機器もない古代において、この地の重要性をどのように知り得たのかは今も謎のままです。さらに鹿島神宮は、地震を鎮めるだけでなく、武力によって平和をもたらした神々を祀る社[やしろ]であり、日本全体の平和と秩序を象徴する存在とされています。In modern times, we tend to view ancient civilizations with the preconception that they were primitive. However, there is no doubt that they possessed “human qualities”—such as sensitivity, intellect, and even morality—that far surpassed those of modern people.

現代の私たちは、古代は原始的であるという先入観をもって捉えがちです。しかし彼らは、感性や知性、さらには道徳性においても、現代人をはるかに上回る「人間力」を備えていたことは間違いありません。 -

The Interwoven Story of Things and People: The Expo | モノと者が織りなす物語、万博

[Japan Style – January 2025 Issue]

The Japan World Exposition (Expo) will be held in Osaka from April 13, 2025, for 185 days.

2025年4月13日から185日間、大阪で「日本国際博覧会」(万博)が開催されます。Various expositions are held around the world, but those officially recognized by the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) are classified into the following four types based on their scale and theme.

世界各地でさまざまな博覧会が開催されていますが国際博覧会事務局(BIE)が認定する「万博」は、規模やテーマによって以下の4種類に分けられます。●Registered Expos: The largest type of expo, addressing global challenges and the future of interna- tional society. In Japan, this will be the third such expo, following the 1970 Osaka Expo and the 2005 Aichi Expo.

●登録博覧会: 国際社会全体の課題や未来を探求する、最も規模の大きな博覧会。日本では1970年の大阪万博、2005年の愛知万博に続き、今回が3回目の開催。●Specialized Expos: Expositions focusing on specific fields such as science, technology, energy, and the oceans. In Japan, past examples include the 1975 Okinawa Ocean Expo and the 1985 Tsukuba Science Expo.

●特別博覧会: 科学技術、エネルギー、海洋などに特化した博覧会。日本では過去に、1975年の沖縄海洋博覧会、1985年の筑波科学万博を開催。●Horticultural Expos: Expositions centered on flowers, greenery, environmental conservation, and urban greening. In Japan, the 1990 Osaka International Garden and Greenery Expo was held, and the Yokohama Interna- tional Horticultural Exposition is scheduled for 2027.

●園芸博覧会: 花や緑、環境保護、都市緑化などがテーマの博覧会。日本では1990年に大阪花博が開催され、2027年には横浜国際園芸博覧会が開催予定。●The Milan Triennale: An exposition specializing in design, fashion, and urban planning, held every three years in Milan, Italy.

●ミラノ・トリエンナーレ: デザイン、ファッション、都市計画などに特化した博覧会 。3年に1度、イタリアのミラノで 開 催 。

© BUNTA iNOUE | 井上 文太

The Bureau International des Expositions (BIE), established in Paris, highlights the deep connection between France and the concept of expos.

パリに設立された「万博」の事務局BIE(The Bureau International des Expositions)は、フランスと万博の深い結びつきを示しています。The roots of the expo can be traced back to the French Revolution (1789). Following the revolution, treasures and artworks from the royal family were made available for public viewing in various locations.

万博の源流はフランス革命(1789年)にまでさかのぼります。革命後、王家の財宝や芸術品が各地で一般公開されるようになりました。

© BUNTA iNOUE | 井上 文太

One of the symbolic initiatives was the opening of the Republic Museum (Musée de la République) within the Louvre Palace in 1793. After major renovations, the entire palace was transformed into a museum.

その象徴的な取り組みの一つとして1793年、ルーヴル宮殿内に共和国美術館(ミュゼ・ドゥ・ラ・ルピュブリック)が開館。その後、ルーブル宮の大改造を経て、宮殿全体が美術館として生まれ変わりました。

© BUNTA iNOUE | 井上 文太

This movement spread across Europe, leading to the establishment of institutions such as the British Museum, the Berlin Museum, and the Hermitage Museum.

この動きはヨーロッパ全土に広がり、大英博物館、ベルリン美術館、エルミタージュ美術館などが誕生します。The public display of royal collections not only elevated national pride and alleviated discontent, but also served as a means to assert cultural superiority over other nations.

王室コレクションの公開は国民の誇りを高め、不満の緩和を促し、他国への文化的優位性をアピールする役割をも果たしました。Looking even further back, records show that in ancient Egypt and Persia, royal coronation ceremonies featured displays of art and royal garments for the public, while in ancient Rome, war spoils and enslaved captives were paraded as symbols of conquest.

さらにさかのぼれば、古代のエジプトやペルシャでは国王即位の祝典で芸術品や王族の衣類が民衆に披露され、古代ローマでは征服戦争で得た戦利品や奴隷が誇示されたことが記録にあります。Humanity may have instinctively understood that showcasing something fosters unity and solidarity.

人類は古来、何かを披露することで連帯が高まることを本能的に知っていたのかもしれません。Britain, the industrial powerhouse, transformed expos from domestic exhibitions into global platforms for nations to promote themselves, with the first World Expo held in London in 1851.

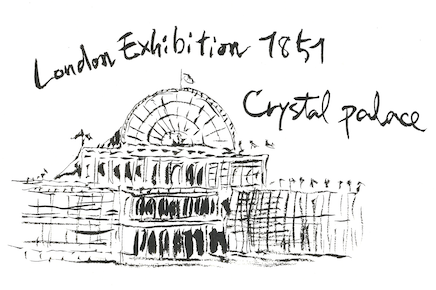

主に自国民向けだった「博覧会」を、自国を世界に向けてアピールする場へと変えたのが、産業革命で台頭したイギリスが1851年に開催した第1回「ロンドン万博」です。Held in London’s Hyde Park, the expo featured the magnificent Crystal Palace, a grand structure covered in approximately 290,000 panes of glass, which became a major highlight.

ロンドンのハイドパークで開催されたこの万博では、約29万枚のガラスで覆われた壮大な建築「クリスタルパレス(水晶宮)」が大きな話題となりました。

© BUNTA iNOUE | 井上 文太

With participation from over 44 countries, Britain showcased the achievements of the Industrial Revolution, including steam locomotives, spinning machines, and the famous diamond loaned by Queen Victoria, asserting its dominant presence.

44カ国以上が参加する中、イギリスは蒸気機関車や紡績機、ヴィクトリア女王が貸し出した有名なダイヤモンドなど、産業革命の成果を豪華に披露し、その圧倒的な存在感を示しました。The London Expo inspired a competitive spirit in other nations, particularly France.

ロンドン万博はフランスをはじめ、他国の競争意識を刺激しました。Among them, the United States acted quickly. Inspired by the London Expo, American entrepreneurs organized the World’s Fair in New York in 1853.

中でも行動が早かったのはアメリカで、ロンドン万博に感銘を受けた実業家たちが1853年にニューヨークで万国博覧会を開催。

© BUNTA iNOUE | 井上 文太

The exhibition featured innovations such as Otis Elevator Company’s lifts, sparking a boom in travel to the United States.オーチス社のエレベーターなど独自の工業製品を展示し、アメリカ旅行ブームを巻き起こしました。

In 1855, the Paris Expo was held at the Champ de Mars. Under the direction of Napoleon III, the expo featured not only industrial products but also artworks and jewelry, showcasing France’s cultural sophistication.

1855年にはパリ万博がシャン・ド・マルスで開催されました。ナポレオン3世の指揮のもと、工業製品だけでなく美術工芸品や宝飾品も展示され、フランスの文化的洗練が大いにアピールされました。

© BUNTA iNOUE | 井上 文太

At this event, French wine was served, and the first official wine classification system was established.

この時に会場でフランスワインが振る舞われ、初の公式格付けが行われます。これが、現在のボルドーワイン格付けの基礎を築いたのです。The competition between France and Britain continued, leading to yet another London Expo in 1862.

フランスとイギリスの競争は続き、1862年には再びロンドンで万博が開催されました。At this time, a delegation from the Edo Shogunate, sent to negotiate the postponement of port openings, arrived in London on April 30, 1862̶the day before the expo’s opening ceremony̶and attended the event the following day.

この時、江戸幕府が「開港延期」交渉のため派遣した使節団が万博開会式前日の1862年4月30日に到着し、翌日の開会式に参加しました。Fukuzawa Yukichi, who would later appear on the 10,000 yen banknote, accompanied the delegation as an interpreter. The delegation, dressed in traditional Japanese attire with topknots and kimonos, became a topic of great interest. Their polite and refined demeanor received high praise from British visitors, contributing to the rise of the Japonisme craze. Meanwhile, the Japanese pavilion, organized by former British envoy Alcock, displayed lacquerware, swords, and lanterns. However, records indicate that the delegation criticized the quality as shabby.

前1万円札の肖像で知られる福沢諭吉も通訳として同行していました。 ちょんまげに羽織袴姿の使節団は話題を呼びました。礼儀正しく上品な振る舞いはイギリス人来場者から高評価を得て、ジャポニズムブームのきっかけとなりました。 一方、元駐日英国公使オールコックによる日本ブースでは漆器や刀、提灯などが展示されましたが、使節団はその品質をみすぼらしいと酷評したという記録が残っています。

© BUNTA iNOUE | 井上 文太

In 1867, another expo was held in Paris, marking Japan’s first official participation. The Shogunate, along with the Satsuma and Saga Domains, exhibited traditional crafts, winning the grand prize in the sericulture category.

1867年、再びパリで万博が開催され、日本は初めて正式に参加しました。幕府、薩摩藩、佐賀藩が伝統工芸品を展示し、養蚕部門でグランプリを受賞しました。

© BUNTA iNOUE | 井上 文太

However, the highlight was a sukiya-style teahouse independently exhibited by a merchant from Asakusa. Three geisha served tea, smoked kiseru pipes, and played hanafuda cards with visitors, leav- ing a lasting impression and earning a front-page feature in Le Figaro.

しかし、最も注目を集めたのは浅草の商人が個人で出展した数寄屋造りの茶屋でした。芸者3人がキセルを吸いながら茶を振る舞い、来場者と花札を楽しむ姿が強い印象を与え、フィガロ誌の1面を飾るほど人気を博しました。畳の上で正座する日本女性の優美さと異国情緒が絶賛され、ジャポニズムブームに大きく貢献しました。

© BUNTA iNOUE | 井上 文太

At the 1873 Vienna Expo, where Japan participated under the Meiji government, they recreated shrines and Japanese gardens, showcasing their culture and asserting the new government’s presence on the international stage.

1873年に明治政府として参加したウィーン万博でも、会場に神社や日本庭園を再現し、文化とともに新政府の存在を国際社会にアピールしました。

© BUNTA iNOUE | 井上 文太

Through subsequent expos, Japan expanded its international recognition, solidifying its status as the“pioneer of modernization in Asia”at the 1910 Japan-Britain Exhibition in London.

その後も万博を通じて日本の国際的な認知を広げ、1910年のロンドンで開催された日英博覧会では、「アジアの近代化の先駆者」としての地位を確立。日英同盟の強化と国際政治での影響力向上の重要な節目となりました。The frequency of expos declined in the 20th century due to two World Wars, but they never ceased entirely.

20世紀には2度の世界大戦を経て万博の開催頻度は減少しましたが、途絶えることはありませんでした。Japan’s reentry into the international community after the war was marked by the 1958 Brussels Expo. At this expo, Japan embraced the theme of “Progress and Harmony,” showcasing its techno- logical prowess and cultural revival while strengthening its global ties.

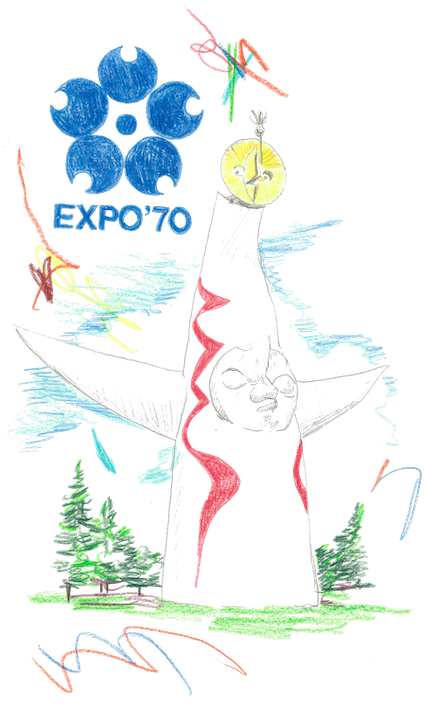

戦後、日本が国際社会に復帰する契機となったのは1958年のブリュッセル万博です。この万博で日本は「進歩と調和」をテーマに掲げ、技術力や文化の復興を世界にアピールし、国際社会とのつながりを深めました。Having achieved post-war recovery, Japan set its sights on an even greater challenge: hosting its own expo, which culminated in the 1970 Osaka Expo. As the first registered expo in Asia, it was held under the theme “Progress and Harmony for Mankind,” drawing 64 million visitors from around the world and achieving great success.

戦後復興を遂げた日本は、さらなる挑戦として万博の自国開催を目指し、1970年に大阪万博を実現します。アジア初の登録博覧会として「人類の進歩と調和」をテーマに掲げ、世界中から6,400万人を迎えるという大成功を収めました。

© BUNTA iNOUE | 井上 文太

The Osaka Expo symbolized Japan’s recovery from war and served as a crucial milestone in establishing its status as an economic powerhouse.

この大阪万博は戦争を乗り越えた日本を象徴するもので、経済大国としての地位を確立する重要な契機となりました。Since then, expos have evolved into international platforms where nations present their unique themes and visions, driven by globalization and technological advancements.

その後、万博はグローバル化と技術革新の進展を背景に、各国が独自のテーマやビジョンを発信する国際的なプラットフォームとして進化を続けています。In 2025, Japan will once again host an expo: the Osaka-Kansai Expo, with the theme “Designing Future Societies for Our Lives.”

そして2025年、再び日本で「大阪・関西万博」が開催されます。テーマは「いのち輝く未来社会のデザイン」。Following the 1970 Osaka Expo, which championed “Progress and Harmony for Mankind significant advancements through technological innovation and attained mate- rial wealth.

「人類の進歩と調和」を掲げた1970年の大阪万博を経た後、人類は技術革新によって大きな進歩を遂げ、物質的な豊かさを手にしました。

© BUNTA iNOUE | 井上 文太

The 2025 Osaka-Kansai Expo is anticipated to offer a space where one can experience a future society in which science, technology, and life exist in harmony.

2025年の大阪・関西万博では、科学技術と命が調和した未来社会を実感できる場となることが期待されています。With the advancement of digital technology, many experiences have now been replaced by online simulations. However, the experience of contact restrictions during the pandemic has led humanity to rediscover the value and wonder of seeing, hear- ing, and feeling real things in authentic places.

デジタル化が進み、多くの体験がインターネット上疑似行為で済まされる時代となりました。しかし、パンデミックによる接触制限を経験したことで、人類はあらためてリアルなモノをその場で目に耳にし、肌で感じることの素晴らしさ、大切さを実感しています。In the 21st century, while we enjoy the benefits of a society abundant in goods, we also face an environmental crisis caused by mass production and its impact on nature.

21世紀の私たちは、モノが溢れる社会の恩恵を享受する一方で、大量生産がもたらす自然破壊によって地球環境の危機に直面しています。Future expos may inherit the stories of “things” and “people” while shifting their focus to “experiences,” thus becoming spaces for discovering new missions.

これからの万博は、モノと者の物語を受け継ぎながら「コト」へと視点を移し、新たな使命に気づく場となるのかもしれません。Now is the time to make the Expo a“place (ba)” where one can experience real “things(koto),”meet many “people (mono),” and become aware of diverse “things (koto).” The “words (kotoba)” discovered there will surely bring new color and richness to the Monogatari of your life.

今こそ「万博」を、実際の「モノ」を体感し、多くの「者」と出会い、多様な「コト」に気づく「場」にしてください。そこで見つかる「コトバ」が、きっとあなたの命の物語に新たな彩りと豊かさを与えてくれるはずです。 -

The Japanese, Given Life by Rice

お米に生かされてきた日本人

[Japan Style – December 2024 Issue]

About 13.8 billion years ago, a flash of light spread through the infinite darkness, marking the Big Bang. Several hundred million years later, galaxies began to form, starting the grand narrative of the universe. The birth of Earth would still require a further 9 billion years.

今から約138億年前、無限の闇の中に閃光が広がり、ビッグバンが起こりました。それから数億年後に銀河が姿を現し、壮大な宇宙の物語が幕を開けたのです。地球の誕生は、さらに約90億年を待つこととなります。The newly born Earth was a wild landscape, with a sea of boiling magma stretching as far as the eye could see. Over time, however, it gradually cooled and solidified, taking shape. Eventually, icy meteorites from Jupiter showered down, filling the surface with water. It is believed that these meteorites also contained carbon, which is considered the source of life.

誕生したばかりの地球は、煮えたぎるマグマの海が広がる荒々しい姿でした。しかし、時が経つにつれて徐々に冷え固まり、形を整えていきました。やがて木星から氷の隕石が降り注ぎ、地表は水で満たされます。その氷には、生命の根源である炭素も含まれていたと言われています。Thus, the blue planet Earth—covered in carbon and water—came into being. Then, a mysterious process of the Sun known as “photosynthesis” began, producing the carbohydrates that serve as the source of life.

こうして、炭素と水に覆われた青い惑星「地球」が誕生したのです。そこに、太陽の神秘的な営みである「光合成」が始まり、私たちの生命の源である炭水化物が生まれました。Now, we move our bodies using the sugars contained in those carbohydrates. From the birth of the universe to the present day, we have been living within this cycle. Carbohydrates have spread in harmony with the natural environments of various regions across the Earth.

今、私たちはその炭水化物に含まれる糖質をエネルギーにして身体を動かしています。宇宙の始まりから今日に至るまで、私たちはこの循環の中で生き続けているのです。炭水化物は地球上のさまざまな土地の自然と調和しながら広がっています。In dry regions, strong wheat grows, while in water-rich areas, moist rice thrives. In warm highlands, corn continues to be cultivated, and in humid tropical islands, taro is grown as a staple, each fostering unique food cultures.

乾燥した地域では力強く麦が実り、水が豊かな土地ではしっとりとした米が育ちます。温暖な高原地帯ではとうもろこしが、湿潤な熱帯の島々ではタロイモが、それぞれ主食として作り続けられ、独自の食文化を育んできました。In Japan, which is blessed with abundant water, rice naturally became the staple food—an indispensable part of our lives. For Japanese people, rice—nurtured by the blessings of the sun, water, and earth—is life itself.

水に恵まれた日本では、やはり米が主食となり、私たちの暮らしに欠かせない存在となりました。米は、まさに太陽と水、そして大地の恵みを受けて育つ、日本人にとって生命そのものなのです。For over 10,000 years, during the Jomon period, the Japanese lived off nature’s blessings by hunting animals, catching fish, and gathering nuts and wild plants.

1万年以上も続いていたとされる縄文時代。日本人は、動物を捕まえ魚を獲り、木の実や山菜を採取して、自然の恵みを頂いて暮らしていました。It has been discovered that primitive rice was cultivated in Fukui Prefecture around this time. Paddy rice farming was introduced from the Chinese continent toward the end of the Jomon period.

この頃すでに、福井県で原始米が栽培されていたことが分かっています。水田稲作が中国大陸から伝わってきたのが縄文時代の終わり頃でした。The large-scale cultivation of rice using paddy fields, which allowed for nutritious and delicious rice to be produced in abundance, spread rapidly during the Yayoi period. As a result, villages centered around rice production emerged, bringing together people specializing in rice farming, pottery making, and tool crafting, leading to settled communities.

おいしくて栄養価が高い米を量産できる水田稲作は、弥生時代になって一気に広がります。それにより、米を作る人、土器を作る人、道具を作る人など米づくりを中心に人が集まる村ができ、定住して暮らすようになります。Rice became a fundamental support for the Japanese spirit and a symbol of power. Leaders emerged to oversee festivals and agricultural activities, with those who possessed rice accumulating wealth and power, creating distinctions in social class and wealth. Competition arose for fertile land suitable for rice production, leading to conflicts to protect stored rice. Stronger villages began to dominate surrounding ones, eventually forming larger nations.

米は日本人の心の支えとなり、さらに支配力の象徴にもなっていきます。祭りや農作業のリーダーとなる指導者が現れ、米を持つものが富と権力を持ち、身分や貧富の差が生まれました。米づくりに適した土地を奪い合うようになり、保存した米を守るための争いも起きます。そして、強い村が周囲の村を支配し、やがて大きな国となっていきました。In 646, a system was established in which the state controlled all land and people. They distributed fields to the people and required them to pay taxes in the form of rice. This tax system continued in various forms until 1873. Rice played an essential role as a form of currency, with salaries paid in rice. It was only in the Meiji era that taxes transitioned from rice to currency.

646年、国が全ての土地と人を支配する制度ができ、人々に田を与えて、米を税として納めさせるようになりました。この納税の仕組みは、形を変えながら1873年まで続きました。米は通貨として重要な役割を果たし、給料も米で支給されました。明治時代になってようやく、税は米から貨幣に変わったのです。In the Edo period (1603–1868), rice production served as a direct indicator of a daimyo’s economic power and authority, measured in units called kokudaka (1 koku = approximately 180 liters). Kokudaka was determined by land surveys conducted by the shogunate, based on the size and productivity of a daimyo’s territory. The daimyo’s tax and military obligations were set according to their kokudaka. Those with higher kokudaka held greater political influence and social status. For example, the Maeda family of the Kaga domain (in present-day Ishikawa and Toyama prefectures) was known as a powerful clan, with kokudaka exceeding one million koku.

江戸時代(1603年~1868年)には、米の生産量が大名の経済力や権力を示す指標とされ、「石高」という単位で計算されました。(1石=約180リットル)石高は幕府が行う検地によって、領地の広さや土地の生産性を基に決定され、大名は石高に応じて年貢や軍役を負担しました。石高が高いほど大名の政治的発言力や地位も高まり、例えば加賀藩(現在の石川県と富山県)の前田家は100万石を超える石高を持つ有力な存在として知られていました。Today, when it comes to Japanese rice available in supermarkets, varieties such as Koshihikari, Hitomebore, Akitakomachi, and Nanatsuboshi are popular. Among them, the top brand is Koshihikari from Uonuma in Niigata Prefecture.

今日、スーパーで売られている日本のお米といえば、コシヒカリ、ひとめぼれ、あきたこまち、ななつぼし……多くの品種がありますが、中でもトップブランドは、新潟県魚沼産のコシヒカリ。Koshihikari, introduced in 1956 after multiple improvements, became popular for its high quality, early harvest, and excellent flavor. It ranks first in planted area and production nationwide and remains highly popular. Its subtle sweetness and soft, chewy texture are widely appreciated.

品種改良が重ねられて1956年に登場したコシヒカリは、出荷が早く高品質、味も良いと評判になりました。作付面積も生産量も全国トップとなり、今も人気が続いています。ほんのりした甘みと、柔らかくもっちりした食感が好まれています。Each year, from mid-September to mid-October, new rice begins appearing in stores across Japan. For Japanese people, new rice is special, with anticipation similar to the excitement for Beaujolais Nouveau in France. Cooking fresh, water-rich new rice brings out glossy, smooth grains. Serve it steaming hot in a bowl, and enjoy it while it’s warm. Although it may be a bit expensive, the taste of new rice is exquisite.

毎年、9月中旬を過ぎ10月も半ばになると、日本全国の新米が店頭に並び始めます。日本人にとって新米は特別。新米を待ち遠しく思うのは、ボジョレーヌーヴォーを想う気持ちと同じでしょうか。水をたっぷり含んだ新米を炊くと、ぴかぴかつるつるの美しい米粒が立ち上がって見えます。ほかほかのご飯を茶碗によそって、湯気の立ったところを召し上がれ。少々高くても、新米の味は絶品です。When we leave the city and see the rice fields changing with the seasons—lush green in the summer and golden during the autumn harvest—every Japanese person feels a deep sense of nostalgia. It is as if this landscape is deeply etched in our blood, sustained by the very life force of rice.

都心を離れて、青々とした夏や黄金色に輝く秋の収穫期など、季節ごとに姿を変える田んぼの景色を目にするとき、私たち日本人は誰もが懐かしさを覚えます。それはまるで、この風景が米の命に生かされてきた私たちの血液に深く記憶されているかのようです。文・岩崎由美

Text ・Yumi Iwasaki -

“Wagyu” Co-Being with “Wajin”

“和人” とともに在る“和牛”。

[Japan Style – November 2024 Issue]

Throughout the world, food cultures rooted in the natural environment have developed in different regions. For example, northern Europe, including northern England and Ireland, is cold and has many grasslands, making it suitable for cattle and sheep grazing. As a result, livestock farming has developed as an important industry.

地球上では、各地で風土に根ざした食文化が育まれてきました。例えば、イギリス北部、アイルランドなどを含むヨーロッパ北部は寒冷で牧草地が多く、牛や羊の放牧に適していることから牧畜が重要な産業として発展しました。In Japan as well, Hokkaido, with its cool climate similar to northern Europe, takes advantage of its vast land for dairy farming. The number of dairy cattle raised there is overwhelming, and the production of raw milk, the base for dairy products, accounts for more than 50% of the nation’s total. Hokkaido also ranks first in the country for beef cattle production, but there is not much production of what is considered “Wagyu.”

日本でも、ヨーロッパ北部に似た冷涼な気候の北海道では、広大な土地を生かして酪農が盛んです。特に乳牛の飼育頭数は圧倒的で、乳製品の原料となる生乳の生産量は全国の50%超。肉牛生産でも全国1位ですが、いわゆる「和牛」とされる肉用牛の生産は多くありません。The place considered the origin of “Wagyu” is Niimi City in Okayama Prefecture. In Niimi City, known for producing high-quality iron sand, farmland was limited, so livestock farming developed as a substitute industry during the Edo period. The cattle raised in this area later became the foundation for Wagyu, which spread nationwide and was gradually improved into what is now known as “Wagyu.”

「和牛」の発祥とされているのが岡山県新見市です。良質な砂鉄の産出地として知られた新見市では耕作地が限られていたため、江戸時代に畜産が代替産業として発展しました。この地で飼育された牛が後に和牛の基礎となって全国へと広がり、現在の「和牛」へと改良されていきました。The three most famous Wagyu brands—Kobe beef, Matsusaka beef, and Omi beef—are known for their beautiful cut surfaces and tenderness. The “Tajima beef” (from the Tajima region of Hyogo Prefecture), which forms the basis of many of these well-known brands, is famous for its long history of bloodline management and breed improvement. In the Kyushu region, brands like “Miyazaki beef” and “Kagoshima Kuro-ushi” (black cattle) are famous for maintaining Wagyu’s superior bloodline while incorporating local breed improvements, and in the Tohoku region, “Yamagata beef” and “Maesawa beef” are well-known.

三大銘柄と言われる神戸ビーフ、松阪牛、近江牛は切断面が美しく、柔らかさが特徴です。これらの知名度が高いブランド牛の多くの基になっている「但馬牛」(兵庫県但馬地方)は、血統管理や品種改良の歴史が深いことで知られています。九州地方では、和牛の優れた血統を引き継ぎつつ地域特有の改良が施されたブランド牛「宮崎牛」や「鹿児島黒牛」が、東北地方では「山形牛」や「前沢牛」が有名です。In Japan, from the birth of a calf to when it becomes meat, everyone involved treats the cattle with great care, paying close attention and showing affection. Each calf is registered with a name, birthdate, bloodline—including parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents—where it was born, and who raised it. Each cow is given an individual identification number. This thoroughly managed traceability (production history) provides peace of mind.

日本では、牛の誕生から食肉になるまで、全ての関わる人たちが丁寧に細やかに心を配り、愛情を注いで扱います。生まれた子牛の名前、生年月日、両親、祖父母、祖父母の父母までの血統、どこの牛農家で生まれ誰が育てたのかといった戸籍があり、1頭ごとに個体識別番号が与えられます。きっちり管理されたトレーサビリティ(生産履歴)は、安心感につながります。Cattle farmers put their hearts into raising the cattle. In addition to grains, they feed the cows rice straw that has been aged for one to two years, and the 20 to 50 liters of water they drink daily is natural spring water. In summer, when the cows’ appetite decreases, they are even given beer. Farmers brush the cows every morning without fail, massage them with shochu, shampoo them to make their coats glossy, and in winter, they even splash cold water on the cows to stimulate the growth of soft, fluffy winter fur. Through constant trial and error, farmers spare no effort or labor.

牛農家は心を砕いて育てます。穀類のほか、1~2年熟成させた稲わらを食べさせたり、1日に20~50リットル飲む水は天然水、食欲が落ちる夏はビールを飲ませたりします。ブラッシングは毎朝欠かさず、焼酎を使って全身をマッサージ。毛並みを美しくするためにシャンプーをし、冬はあえて冷たい水をかけて身体を冷やしてふわふわの冬毛が生えてくるようにするなど、手間と労力を惜しまず試行錯誤を繰り返してきました。Cattle that are carefully raised like family by skilled and dedicated producers have calm expressions and beautiful physiques. It is said that the better the cow looks, the better the meat tastes. When it’s time for shipment, farmers reportedly pray, saying, “Thank you for growing up so well. Now, please go on to sustain the lives of many people.” They feel pride in raising cows that will become essential to human life and express gratitude to the cows for supporting human existence.

生産者の技術と人柄で家族のように大切に育てられた牛は、顔つきが穏やかで体軀も美しくなります。牛は見た目に比例して肉の味も良くなるのだそうです。出荷となり送り出す時、「ここまで育ってくれてありがとう。この先はたくさんの人の命になってくれ」と祈るのだとか。牛農家は、人間の命を支えてくれる牛に感謝しながら、育てた牛がみんなの命になることに誇りを持って育てています。Today, “Japanese Wagyu” has become incredibly popular worldwide and is recognized as Japan’s finest food product. The characteristic of “Japanese Wagyu” lies in its “marbled meat,” where fat is interwoven like a web among the lean meat, creating a melt-in-your-mouth richness. This is rare overseas and has garnered high praise. The tender meat, which can be cut with chopsticks, and the sweet fat that spreads in your mouth can only be experienced with Wagyu raised in Japan.

今や「日本の和牛」は世界で大人気となり、日本が誇る最高の食材となりました。「日本の和牛」の特徴は、赤身の間に網の目のように入ったサシ(脂肪)がとろけるような旨みを生み出す「霜降り肉」にあります。これは海外では珍しく、高い評価を得ています。箸で切れるほどに軟らかく、口の中に甘さが広がる良質な肉の脂は、日本で育てられた和牛でしか味わえません。Looking around the world now, Wagyu crossbred with Japanese bloodlines, known as Wagyu, is flourishing overseas. Australia, in particular, is the largest producer of Wagyu and has gained significant recognition. However, it is a completely different product from the Wagyu produced in Japan. Japanese Wagyu, raised with the passion and dedication of farmers who tend to their cattle daily, offers a deep flavor, smooth texture, and melt-in-your-mouth harmony that will be etched in your memory once you taste it.

今、世界を見渡すと、和牛の遺伝子を交配した海外産のWagyuが幅を利かせています。特にオーストラリアは最大のWgyu生産国で、知名度も高いのが現状ですが、日本で生産される和牛とは全くの別物です。真摯に日々牛に向き合う生産者の情熱とこだわりが込められた和牛は、一度口にすれば奥深い風味と滑らかな舌触り、とろける口当たりのハーモニーが記憶に刻み込まれることでしょう。 -

[Japan Style – October 2024 Issue]

Tanka for Being in the Now

今を生きるための短歌What do you do when your heart is unsettled? One way to escape when you’re about to be crushed by stress is through “mindfulness,” which has gained global attention. This meditation method focuses the mind on the “present.”

心が乱れたら、どうしていますか。ストレスで押し潰されそうになった時に、そこから抜け出す方法の一つとして世界的に注目されている「マインドフルネス」。これは、意識を「今」に集中させる瞑想法です。When you think about it, “tanka” (or “waka”), one of Japan’s unique traditional cultural practices that has continued for over 1,300 years, serves as an excellent method to pause and calm the mind. Whether composing or appreciating a tanka, one first directs one’s awareness inward and faces one’s own emotions.

考えてみると、1300年以上続く日本固有の伝統文化の一つ「短歌(和歌)」は、立ち止まって心を静める手法としてとても役立ちます。歌を詠む時、鑑賞する時、人はまず意識を内面に向け、自身の感情と向き合います。By doing so, you can begin to see what you are truly feeling and what you are seeking. Tanka, considered the source of Japanese culture, may offer such benefits.

すると、自分が本当は何を感じているのか、何を求めているかが見えてきます。日本文化の源[ルビ:みなもと]とも言える短歌には、そうした効用もあるかもしれません。For over 60 years, the “Taiga Drama,” which airs every Sunday night on NHK, has featured various historical figures as its protagonists. This season (starting January 2024), the protagonist is Murasaki Shikibu. Murasaki Shikibu is known as the author of “The Tale of Genji,” the world’s oldest full-length novel, completed about 1,000 years ago, and she was also a highly educated poet (a composer of waka).

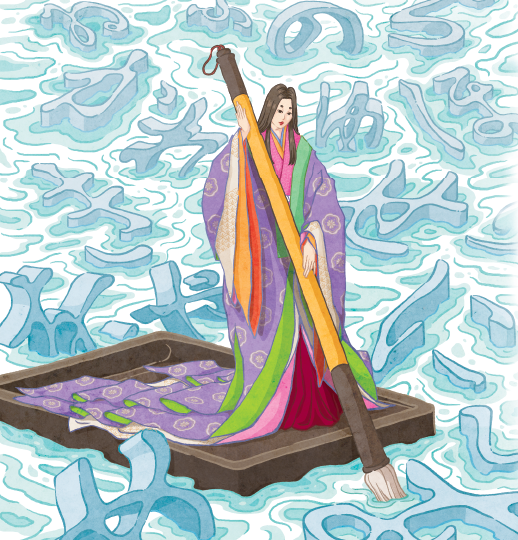

60年以上にわたり毎週日曜夜にNHKで放送されている「大河ドラマ」。今シーズン(2024年1月~)の主人公は紫式部です。紫式部と言えば、1000年ほど前に完成した世界最古の長編小説『源氏物語』の作者として知られ、教養あふれる歌人(和歌を詠[よ]む人)でもありました。In The Tale of Genji, nearly 800 waka poems appear at key points in the story. This season’s Taiga Drama also includes scenes where poems are composed, subtly revealing the poet’s personality while addressing an unrequited lover without mentioning names. It is indeed an elegant and subtly alluring portrayal.

『源氏物語』には800首近い和歌が織り込まれていて、物語の要所要所で登場します。今の大河ドラマにも、かなわぬ恋の相手に向けて名前を伏せ、自分らしさがそこはかとなくわかるような歌を詠む場面が織り込まれています。何とも奥ゆかしく、色気が漂うではありませんか。Waka is a fixed-form poem written in 31 syllables in a 5-7-5-7-7 pattern. The poet expresses one’s inner feelings and emotions.

和歌は、五七五七七の三十一文字(みそひともじ)で書かれる定型詩です。作者は感覚や心情といった心の内を表現します。Because the number of words is fixed, the poet’s thoughts are condensed, and the reader expands one’s imagination to savor that world. The reader may sense the spirit beyond the literal meaning of the words, finding empathy or inspiration.

定型で言葉数が決まっているぶん、作り手の想いが凝縮され、読む人は想像を広げてその世界を味わいます。言葉の向こうにある言葉そのものの意味を超えた魂を感じて共感したり感動したりする。How one interprets a tanka depends greatly on one’s own experiences, education, and sensitivity. The richer these are, the more one can feel. It’s not necessary to correctly grasp what the poet wanted to convey. One is encouraged to understand it in one’s own way.

何をどう捉えるかは、読む人それぞれの経験や教養、感受性によるところが大きく、それらが豊かであるほど多くのことを感じられるでしょう。歌を詠んだ人の伝えたかったことを正しく読み取れなくてもいい。各々の捉え方で理解すればよいとされています。The oldest tanka anthology in Japan is the “Manyoshu.” It contains about 4,500 poems from the 7th to 8th centuries. The authors range from emperors to commoners across Japan. They sing of reverence, awe, and praise for nature, love for family or lovers, and discoveries in daily life, covering a wide variety of themes.

日本最古の和歌集は「万葉集」です。ここには7~8世紀頃の歌約4,500首が収められています。作者は天皇から平民まで日本各地に住む幅広い層の人たちです。自然を畏怖し、敬い、讃美する。家族や恋人への愛や日常の暮らしの中での発見など、さまざまなテーマで詠まれています。

During the Heian period (794–1185), a time of cultural flourishing, waka often depicted natural landscapes such as flowers, birds, wind, and the moon using native Japanese words. The soft sounds when recited aloud and the refined use of language were essential cultural knowledge for both men and women in aristocratic society. Especially in matters of love, waka was indispensable for conveying emotions.

文化が爛熟した平安時代(794~1185年)の和歌には、日本固有の大和言葉で花や鳥、風や月といった自然の姿がよく詠まれました。和歌は、声に出した時の音の響きが柔らく格調高い言葉で詠むことがよしとされ、貴族社会において男女共に必須の教養でした。特に恋愛において気持ちを伝えるのに、和歌はなくてはならないものでした。At that time, it was considered improper for a woman to express her feelings to a man first. Even if a man confessed his feelings, replying with “I like you too” was considered unsophisticated. It was considered more refined to deflect with something like, “Aren’t you saying the same thing to someone else?”

当時は、女性から先に男性に想いを伝えるのは「はしたないこと」とされていたのです。男性から想いを告げられても「私も好きです」と返すのは野暮で、「私以外の方にも同じことを言っているのではないですか」などと受け流すのが風流だとされました。To reject someone, it was enough not to respond, much like what we would now call “read and ignore.” Direct expressions like “I’m happy” or “I’m sad” were also avoided; instead, words were chosen that would subtly convey those feelings.

National Treasure | Genryaku Manuscript of the Manyoshu [Tokyo National Museum Collection]

拒絶する時は、現代の既読スルーのように返事をしなければ良いのです。また、嬉しい悲しいといった直接的な言葉を入れるのもNG。それを感じさせるような言葉を選びます。One of the works often studied in schools is the “Ogura Hyakunin Isshu (One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each),” compiled during the Kamakura period (1180–1336). This anthology consists of 100 poems, each composed by a different renowned poet.

学校で習うことが多い和歌集に、鎌倉時代(1180年~1336年)に編纂された『小倉百人一首』があります。これは優れた歌人100人の和歌を1人1首ずつ、計百首を選んで作られた歌集です。Japan’s national anthem, “Kimigayo,” was also taken from the “Kokin Wakashu,” which was

compiled by imperial order in 905.

日本の国家「君が代」も、905年に天皇の命によって編集された「古今和歌集」から採られました。

Waka began to be called “tanka” during the Tanka Reform Movement in the late Meiji period (1887–1906), led by poets such as Masaoka Shiki and Yosano Tekkan. Before then, it was believed that only lofty subjects should be expressed in poetry, but the movement allowed anything in daily life to become the subject of a tanka.

「和歌」が「短歌」と呼ばれるようになったのは、明治20年代から30年代(1887〜1906年)にかけて正岡子規、与謝野鉄幹といった歌人の提唱で起こった短歌革新運動によるものです。それまでは高尚な題材を詠むべきとされていたのが、身の回りにあるどんなものも歌に詠んでよいとしました。Yosano Akiko wrote about sensuality and romantic feelings, while Ishikawa Takuboku wrote about poverty. With this liberation of themes, the world of tanka blossomed greatly.

与謝野晶子は官能や恋愛感情を、石川啄木は貧しさを詠むなど、テーマが開放されたことで短歌の世界は大きく花開きました。

The next shockwave after the Tanka Reform Movement was the tanka composed by Tawara Machi in everyday spoken language. Her poetry collection Salad Anniversary (1987) captured the hearts of people who were not usually familiar with tanka and became a huge bestseller, selling over 2 million copies.

さて、短歌革新運動の次に訪れた衝撃は、身近な話し言葉で作られた俵万智の短歌でした。彼女の出した歌集「サラダ記念日」(1987年)は普段、短歌になじみのない人の心もつかみ、200万部を超える大ベストセラーとなりました。With the start of the Reiwa era, another tanka boom has emerged. The number of people composing tanka, especially among those in their 20s and 30s, has increased, leading to more publications of tanka collections. Bestsellers have appeared, and tanka events held across the country are thriving. On social media, hashtags like “#tanka photo” and “#tanka” see new poems being posted almost every minute. Over 70,000 tanka are submitted to the “Modern Student Hyakunin Isshu” competition, which has been held since 1987 and attracts students from Japan and abroad.

そして令和になり、また短歌ブームが来ています。20代から30代の若い世代を中心に短歌を詠む人が増え、歌集の出版が続いています。続々とベストセラーが生まれ、各地で開かれる短歌イベントも大盛況です。SNSのハッシュタグ「#短歌フォト」「#tanka」には、新しい歌が毎分のように投稿されています。1987年から続く、国内外の学生を中心としたコンクール「現代学生百人一首」には、7万首を超える歌が集まります。One of the appealing aspects of tanka is the immediate feedback from readers when shared on social media. Unlike haiku, tanka does not require a seasonal word, and its fixed form makes it relatively easy for beginners to compose, which seems to add to its popularity.

短歌は、SNSで発信すればすぐに読者からの反応があることも魅力の一つです。俳句と違って季語がいらず、定型なので初心者でも作りやすいという気軽さもウケているようです。By mobilizing all senses—sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch—we explore the depths of the heart and express it in words. This method of expression has been passed down through the ages, updated with the times, and has always reflected the hearts of the people of each era.

視覚・聴覚・味覚・臭覚・触覚といった全ての感覚を総動員して心の深いところを探り、言葉にして表現する。その表現方法は長きにわたって受け継がれ、時代とともにアップデートされ、その時代の人々の心を写し出してきました。Waka also has strong musical elements, with its pleasing rhythm and beautiful sound when recited aloud. Sometimes, waka is even used in place of norito (Shinto prayers) in sacred ceremonies. Words are meant to be a helping force in life, not a weapon. Surely, they can resonate with the heartbeat of the universe and the human heart, and save us.

和歌はリズムが良く、声に出すと響きが美しいという音楽的要素も強い。時には、神事で祝詞[のりと]の代わりに和歌が詠まれることもあります。本来、言葉は刃でなく、生きる助けになってくれる力であるはず。宇宙の鼓動と人間の鼓動を共鳴させ、私たちを救い出してくれるに違いありません。Text: IWASAKI Yumi

文:岩崎由美 -

[Japan Style – October 2024 Issue]

Echoes of Spirit on Stage – Japanese Languages and Kabuki [Part2]

舞台に響く言霊日本語と歌舞伎 [パート2]

“Kabuki is like Japan’s imperial family. It values bloodlines above all, and if there is no legitimate son, they adopt to ensure the lineage continues. It is a unique environment, for better or worse. Since my parents’ divorce, I had no connection with Kabuki.

「歌舞伎は日本の天皇家と同じです。何よりも血脈を重視し、嫡男がいなければ養子を迎えるなどします。とにかく家系を途絶えさせるわけにはいかない。良くも悪くも特殊な環境にあるのです。親が離婚して以来、私と歌舞伎は無縁になりました。That doesn’t mean I harbored any resentment. I was raised without feeling lonely, even in a fatherless household, because I had parted from my father too early. After graduating from university, I aimed to become an actor in drama and film.”

だからといって悔しい思いをしたということはありません。そして、あまりに早く父と別れたので、父親が不在の家庭であっても寂しさを感じることなく育ちました。大学卒業後は、ドラマや映画の俳優を目指しました」Chusha is better known as Teruyuki Kagawa, an actor. His notable works include the “Hanzawa Naoki” series and the NHK Taiga drama “Ryomaden.” He is highly regarded for his strong, distinctive acting ability.

中車さんは、歌舞伎役者としてより俳優・香川照之(本名)として知られています。代表作はドラマ「半沢直樹」シリーズや大河ドラマ「龍馬伝」など。個性の強い圧倒的な演技力で高い評価を得ています。The reason he returned to the Kabuki stage, which he thought he had lost connection with, was the presence of his newborn son.

中車さんが、もう縁のないものと考えていた歌舞伎役者として舞台に立つことになったのは、誕生した息子の存在だったといいます。“My son is the grandson of En’o. He was born to perform Kabuki. I felt it suddenly. After nearly ten years of contemplating my son’s future, I finally decided to introduce him to the Kabuki world. In 2012, my son assumed the name of the fifth-generation Ichikawa Danko. At the same time, I assumed the name of the ninth-generation Chusha (note: the fourth-generation Ennosuke was inherited by Chusha’s cousin). That was 13 years ago, when I was 45.”

「息子は父・猿翁の孫にあたる。歌舞伎をやるために男子として生まれてきたのだ。ふと、そう、ふと感じたのです。それから10年近く息子の行く末について逡巡し、最終的に歌舞伎界に入れようと決意しました。2012年に息子が五代目市川團子を襲名します。それと同時期に、私も九代目中車を襲名するに至ったわけです(※四代目猿之助は中車の従弟が継承)。それが13年前、45歳の時のことです」。Typically, one cannot work under two names in the Kabuki world, but Chusha, already active as a popular actor, was granted a special exception.

通常、歌舞伎界においては二つの名を持ち活動することはできないのですが、中車さんはすでに人気俳優として活躍していたことから、特例として現在に至っています。“Looking back now, I think it was fate for our family to experience such turbulence. I believe it was predestined by heaven for me to be born into this family. Buddhism teaches ‘reincarnation,’ the belief that people are reborn after death. I believe in this, and I deeply feel that life circulates in this way.”

「今思いますのは、このような波乱の家なのだろうということ。そして、私がこの家に生まれ出ずることは、きっと天が決めていたのだと受け止めています。仏教には輪廻転生という、人は死後再び生まれ変わるという教えがありますが、私はそれを信じていますし、まさにこうして命が循環しているということを、私なりに深く感じています」During the interview, Chusha impressed us with his strong presence, passion, and sense of independence. He is also knowledgeable about historical texts, such as the “Nihon Shoki,” which are vital to historical Kabuki performances like “Yamato Takeru.” His extensive knowledge of Japanese history and culture, along with his keen intellect, left a strong impression.

インタビユーを受ける中車さんは目力が強く、熱情にあふれ、独立自尊を感じさせるに十分な人物でした。また、歌舞伎、特に時代物の演目の重要な幹である歴史書、例えば『ヤマトタケル』における「日本書記」などの書物に精通しており、日本の歴史や文化についても博識で、非常に聡明な印象も受けました。“These qualities may stem from his time spent at a Christian school during his middle and high school years and from studying social psychology at university. He has a deep understanding of the ancient Japanese language, ‘Yamato Kotoba,’ which is the foundation of Kabuki, and graciously accepted our request to write for our serialized column, ‘Nihongo Do.’

それらの根底には、中学・高校時代をキリスト教学校で過ごし、大学で社会心理学を学んだことが大きくあるのかもしれません。歌舞伎の母体とも言っていい古[いにしえ]の日本語「大和言葉」については造詣が深く、弊誌で連載の「日本語道」での執筆ご依頼したところ、快く引き受けてくださいました。“Japanese is a language that includes hiragana, katakana, and kanji, making it extremely difficult for foreigners to learn. Are you struggling with it? (laughs) I believe Japanese is the most unique and mysterious language on Earth.

「日本語は、ひらがな、カタカナ、漢字とあり外国の方にとっては大変に難しい言語だと思います。この雑誌で学んでいる皆さん、苦労していませんか?(笑)。私は、日本語は地球上でもっとも特殊で不思議な言葉だと思っています。」In my opinion, languages like English are ‘horizontal connections.’ It’s an exchange between ‘me and you,’ facing each other. ‘I think this,’ ‘You think that.’

私が考えるのは、英語をはじめとする他国の言語は“横のつながり”であるということ。今向き合って会話をしている“私とあなた”という形。「私はこう考える」「あなたはこう考える」という対面する相互のやりとりです。However, Japanese is a ‘vertical connection.’ I call it a ‘vertical language,’ where, even while conversing with someone in front of you, there is a constant connection to the heavens through words.”

しかし、日本語は“縦のつながり”です。私はこれを「垂直言語」と呼んでいるのですが、目の前にいる人と会話をしながらも、言葉を介して常に天とつながっているような感覚があるのです。」“We could say ‘heavens’ refers to God, but it is more about a grand cosmic existence or ‘consciousness.’ “

「天とは神と言ってもいいですが、どのような神かということではなく、もっと大いなる宇宙的な存在、“意識”と言ってもいいと思います。」Therefore, Japanese people can understand each other through the resonance of words without detailed explanations. In ancient times, when Japanese mythology was written, this connection to the heavens was much purer and stronger. The creation of the fifty sounds and katakana has a very spiritual background.”

ですから、日本人同士は詳しく説明しなくても、言葉の響きで互いに分かり合えるところがあるのです。古代、日本神話が書かれた頃には、この天とのつながりがもっと純粋に強かったことでしょう。五十音やカタカナが生み出された背景はとてもスピリチュアルな面を持っていると言ってよいかもしれません。」“Japan has the concept of ‘kotodama,’ which means that words contain a soul. Shintoism speaks of ‘Yaoyorozu no Kami,’ the belief that everything in this world, including people, the sun, rain, snow, wind, mountains, seas, flowers, and even a single leaf, a pen, or a coffee cup, is inhabited by gods. This delicate sensitivity and spirituality are the essence of the Japanese language. Starting this month, I hope to convey its beauty to you all in depth through the Nihongo do corner in this magazine.”

「日本には「言霊」という言葉があります。まさに言葉には魂が宿っている、ということです。「八百万[やおよろず]の神という神道[しんとう]表現があります。この世の森羅万象の全て、人にも、太陽にも雨にも雪にも風にも、山にも海にも、草花や樹々の1枚の葉っぱ、ペンやコーヒーカップにさえも神が宿っていると感じる。そのような繊細な感受性と精神性を秘めている。それが日本語の本質なのです。本誌「日本語道コーナー」でその美しさを、皆さんにじっくり伝えていけたらと思っています」Text: MIZUTA Shizuko

文: 水田 静子 -

Echoes of Spirit on Stage – Japanese Languages and Kabuki 舞台に響く言霊日本語と歌舞伎

- Hiragana Times

- Sep 13, 2024

[Japan Artist – September 2024 Issue]

Echoes of Spirit on Stage – Japanese Language and Kabuki (Part I)

舞台に響く言霊 – 日本語と歌舞伎

As Japan’s representative traditional performing art, Kabuki is the first to be listed. Kabuki developed from the dance started by Izumo no Okuni in Kyoto in the early Edo period (1603) and eventually came to be performed in theaters. By the mid-Edo period (1680s), it was enjoyed as entertainment for the common people, and Kabuki’s popularity reached its peak.

日本を代表する伝統芸能として、真っ先に挙げられるのが「歌舞伎」です。江戸時代の初め(1603)、京都で出雲阿国[いずものおくに]が始めたかぶき踊りが発展し、やがて芝居小屋で演じられるようになりました。江戸中期(1680〜)には庶民の娯楽として楽しまれ、歌舞伎人気が隆盛を迎えます。

Like modern theater, movies, and TV dramas, Kabuki depicts contemporary events and customs in a narrative format, expressing the joys and sorrows of life. Many performances include criticism and satire of the shogunate and authorities, making it a welcome entertainment for the common people. Performances such as “Sugawara Denju Tenarai Kagami,” “Kanjincho,” and “Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura,” which are based on historical events from the Heian and Kamakura periods, gained high popularity. These works depict the transience of the samurai era, filled with injustice, and continue to move us as representative works of Kabuki.

現代で言う演劇、映画、テレビドラマと同じで、世相や風俗を物語仕立てで見せ、人生の悲喜こもごもを表現。幕府や権力者への批判や風刺を含む演目も多々あり、庶民の溜飲を下げる娯楽として大いに歓迎されていました。遠く平安時代や鎌倉時代の歴史的な事件をモチーフにした『菅原伝授手習鑑』『勧進帳』『義経千本桜』といった演目は高い人気を得ていました。理不尽がまかり通っていた武士の世の無常を描き、歌舞伎の代表的作品として今なお私たちに感動を与え続けています。

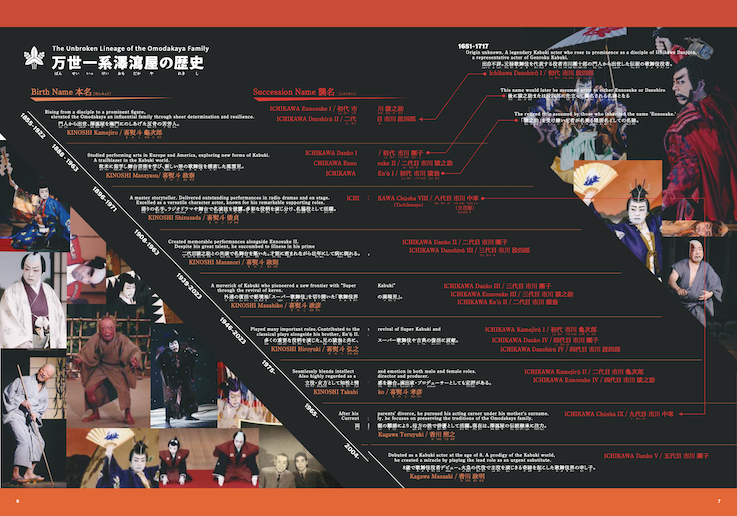

In the world of Kabuki, where traditional techniques (kata) and family stage names (myoseki, artistic names) have been passed down through generations, there are currently 16 family lineages, each with its own “yagō” (house name). Among them, the Ichikawa Danjuro family, known as “Narita-ya,” forms the foundation of the Kabuki world and is currently in its thirteenth generation.

伝統の技芸(型)や名跡[みょうせき](芸名)が代々受け継がれ今に至る歌舞伎界には、現在16の家系があり、それぞれに「屋号」一門、一家の名称)があります。中でも歌舞伎界の土台となっている市川團十郎家は「成田屋」と言い、当代で十三代目。

Other notable families include the Onoe Kikugoro family, known as “Otowaya,” the Matsumoto Koshiro family, known as “Koraiya,” and the Nakamura Kanzaburo family, known as “Nakamuraya.” Ichikawa Chūsha (Ninth-generation) is a Kabuki actor from the Omodakaya family. Omodakaya is considered a maverick among Kabuki families, known for its innovative spirit since the first generation, presenting new interpretations of classics and breaking traditional norms.

他に尾上[おのえ]菊五郎家の「音羽屋[おとわや]」、松本幸四郎家の「高麗屋[こうらいや]」、中村勘三郎[かんざぶろう]家「中村屋」などがあり、市川中車さん(九代目[くだいめ])は、澤瀉屋[おもだかや]一門の歌舞伎役者です。澤瀉屋は並み居る歌舞伎一門の中でも、初代から革新的なスピリットを持ち、古典の新たな演出や伝統を打ち破る演目を発表してきた、異端と称される一門です。

“Since the Meiji era, Kabuki, which was originally popular entertainment for the common people, has become strangely formal. The rebellious spirit of Omodakaya did not accept this. My father, the third-generation Ichikawa Ennosuke (deceased in 2023), was concerned about the current state of Kabuki, where only traditional performances were staged. He created a performance called ‘Yamato Takeru,’ branding it as ‘Super Kabuki,'” Chusha said.

「明治時代以降、それまで庶民の芝居であったはずの歌舞伎が、妙に格式の高いものになってしまった。反骨の精神を持つ澤瀉屋はそれをよしとしませんでした。私の父である三代目市川猿之助(2023年逝去)は、伝統に捉われた演目ばかりが演じられる現状を危惧して『ヤマトタケル』という演目を作り上げ、スーパー歌舞伎と銘打ったのです」と中車さんは語ります。

“Yamato Takeru” is a story based on the legend of Yamato Takeru no Mikoto, as written in the “Nihon Shoki” and “Kojiki,” depicting his tumultuous life. It is a profound work that explores human relationships, conflicts, and the question of why people are born and live.

「ヤマトタケル」は、「日本書記」や「古事記」に書かれている日本武尊(やまとたけるのみこと)の伝説をもとに、その波乱の生涯を描いた物語です。父帝[ちちみかど]との確執をはじめとする人間模様、争い、そして、人はなぜ生まれ生きるのかを問う深遠な作品です。

“Ennosuke (the third-generation Ichikawa) revived ‘keren’ (theatrical tricks) such as ‘chūnori’ (actors flying above the stage on wires), which were performed in Edo Kabuki. The primary goal was to excite and delight the audience.”

「(三代目市川)猿之助は、江戸歌舞伎で行われていた宙乗り(役者が吊られて劇場の上空を飛ぶ演出)といった外連[けれん](奇抜な仕掛け)を復活させました。お客様が沸き、喜んでくだることを第一としたのです」

The premiere of “Yamato Takeru” was 38 years ago. Despite harsh criticism that “it is not Kabuki but a circus,” it was a huge hit, attracting one million viewers. Today, it stands as a representative work of Omodakaya’s lavish spectacles. This year, Chusha’s son, the fifth-generation Ichikawa Danko (20 years old), played the role of Yamato Takeru alongside Hayato Nakamura (Manyoya) in a double cast, garnering significant attention.

「ヤマトタケル」の初演は38年前。「あれは歌舞伎ではない、サーカスだ」とさんざん非難されつつも100万人を動員する大ヒットを記録。今では、澤瀉屋の絢爛豪華な大スぺクタルものとして代表作になっています。今年は、中車さんの息子である五代目市川團子[だんこ](20歳)が、中村隼人(萬屋)とWキャストで主人公・ヤマトタケルを演じて、大きな話題を呼びました。

“Originally, it was a performance requested by the philosopher Takeshi Umehara, with whom my father, the second-generation En’o, was close. The reason the work maintains its dignity despite incorporating ‘keren’ elements is Umehara’s understanding and respect for the foundation of Japan and the inherent dignified spirituality of ancient Japanese people. The actors’ solid foundation in Kabuki (kata) also helps maintain this dignity”. This is reflected in the beautiful final scene where Yamato Takeru dies and ascends to the heavens as a white bird, deeply moving the audience.

「そもそもは、父(二代目猿翁[えんおう])が親しくしていた哲学者の梅原猛先生に頼み込み、原作を書いていただいた演目です。外連の要素を持ち込んでも作品の品格が保たれているのは、日本国の成り立ちに関する先生の理解と敬い、古来日本人が持つ凛とした精神性が底流にあるからでしょう。そして、役者たちのしっかりした歌舞伎の基礎(型)があることも、品格の保持を助けています」それらは、ヤマトタケルが死して白鳥となり天翔けていく美しいラストシーンへとつながり、観る者を感動の渦に巻き込んでいきます。

Each lineage in the Kabuki world has a truly dramatic history. Chusha himself had a unique fate. Born as the son of the third-generation Ennosuke, he was expected to succeed him as the fourth-generation Ennosuke. However, when he was one year old, his parents (his mother was a famous actress) separated, and they divorced when he was three. Raised by his mother, he distanced himself from the Kabuki world.

歌舞伎界は一門それぞれが実にドラマチックな歴史を持っています。中車さんも数奇な運命を背負った人でした。三代目猿之助の子として生まれ、そのままいけば四代目猿之助として大名跡を継いでいたはずなのですが、1歳の時に両親(母は大女優)が別居し、3歳の時に離婚が成立。母親に育てられたため、歌舞伎界からは遠のくことになりました。

Text: MIZUTA Shizuko

文: 水田 静子 -

Connecting to the Future, MINGEI – 未来につなげる民藝

[Japan Style – May 2024 Issue]

Approximately 200 years ago, the Industrial Revolution drastically transformed people’s lives. Mechanization enabled mass production, fueling mass consumption and industrializing nearly everything. Technological innovation gave birth to capitalism, divided into capitalists and the working class. It also fostered mass marketing and media, creating numerous brands. The oldest fashion magazine, “VOGUE,” was published in 1892. Various events and objects became fashioned, with celebrity status increasingly celebrated.

今から約200年前の産業革命は、人々の生活を激変させました。機械化によって大量生産が可能となり、大量消費が促ながされ全てが産業化していきました。技術革新は資本家と労働者階級に分断された資本主義を生み、マスマーケティングとメディアを発達させ、数々のブランドを生み出しました。最古のファッション誌「VOGUE」が出版されたのも1892年のことです。さまざまな事象や物がファッシ ョン化され、セレブリティであることが称賛されるようになっていったのです。

About 100 years later, the “Mingei Movement” emerged, advocating for reviving people’s innate aesthetic consciousness. It is believed the idea that beauty lies not in mass-produced goods or famous artists or designers but in everyday objects surrounding us. It’s the belief that beauty lies in everyday objects around us, not in mass-produced items, nor in the names or brands of famous artists or designers. “Even though they may not be labeled as ‘first-class’ or historically esteemed, aren’t there many beautiful things among the items we use in our daily lives? Let’s pay attention to folk crafts that possess a simple and warm beauty. There lies a beauty of randomness, not deliberately pursued sophistication or skill, in these artifacts.” In everyday life, there is beauty in nameless objects called “zakki .” There, the beauty of living emerges. Mingei (folk crafts) are beautiful handmade items made for practical use. And the philosopher YANAGI Soetsu (YANAGI Muneyoshi) led the “Mingei Movement.”

その約100年後。人々が本来持っている美意識を取り戻すことを提唱した「民藝運動」が誕生しました。大量生産された物ではなく、また、逆に有名な作家かやデザイナーなどの名前やブランドがあるわけではない、身近にある物たちが美しいという考えです。「一級」と言われたり、歴史的に評価されているわけではないけれど、普段、私たちが生活の中で使っている物の中に美しい物がたくさんあるではないか。素朴で温かみのある美しさを持民藝品に注目しよう。作為的に趣向を突き詰めて美しくしようとか、技巧を凝らそうとしていない無作為美しさがそこにはあります。いつもの暮らしにある、「雑器」と呼ばれる名もなき物にこそ美がある。そこに、生きることの美しさが現われています。使うことを目的に作られた美しい手作り品が民藝であり、その運動「民藝運動」を主導したのが思想家・柳宗悦です。

The “Mingei Movement,” aimed at spreading this new beauty, was led by Yanagi, along with potters HAMADA Shoji, KAWAI Kanjiro, TOMIMOTO Kenkichi, and the British Bernard LEACH. Eventually, dyer SERIZAWA Keisuke and printmaker MUNAKATA Shiko also joined, expanding it greatly.

こうした新しい美を広める「民藝運動」は、柳を中心に、陶芸家の濱田庄司、河井寛次郎、富本憲吉、イギリス人じんのバーナード・リーチにより進められ、やがてそこに染色家の芹沢銈介、版画家の棟方志功も加わり、大きく広がりました。